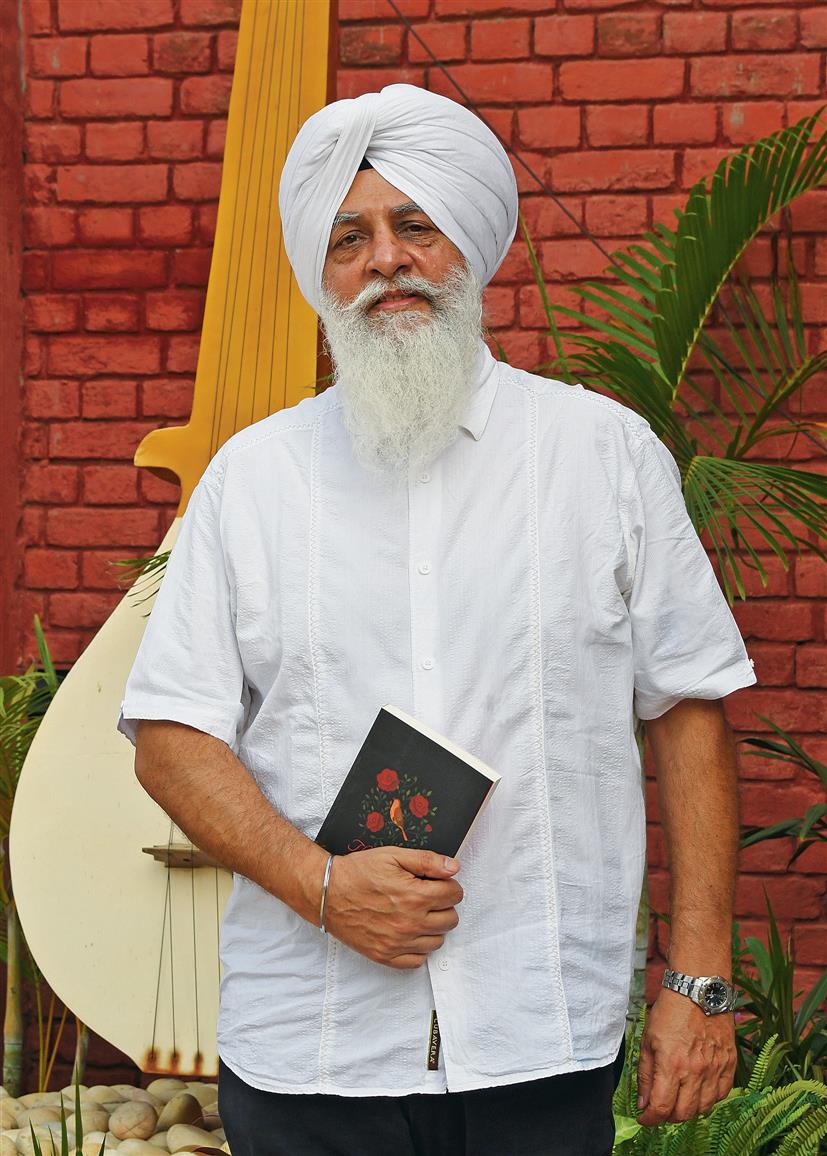

Sarbpreet Singh, a playwright, poet and a commentator is most widely known for penning down The Night Of Restless Spirits, The Camel Merchant of Philsdelphia, The Story of Sikhs: 1469 -1708 and Kultar’s Mime, a poem on the 1984 Sikh Genocide. Singh also founded and runs Gurmat Sangeet Project, a non-profit dedicated to the preservation of traditional Sikh culture. His podcast has been listened to in over 90 countries.

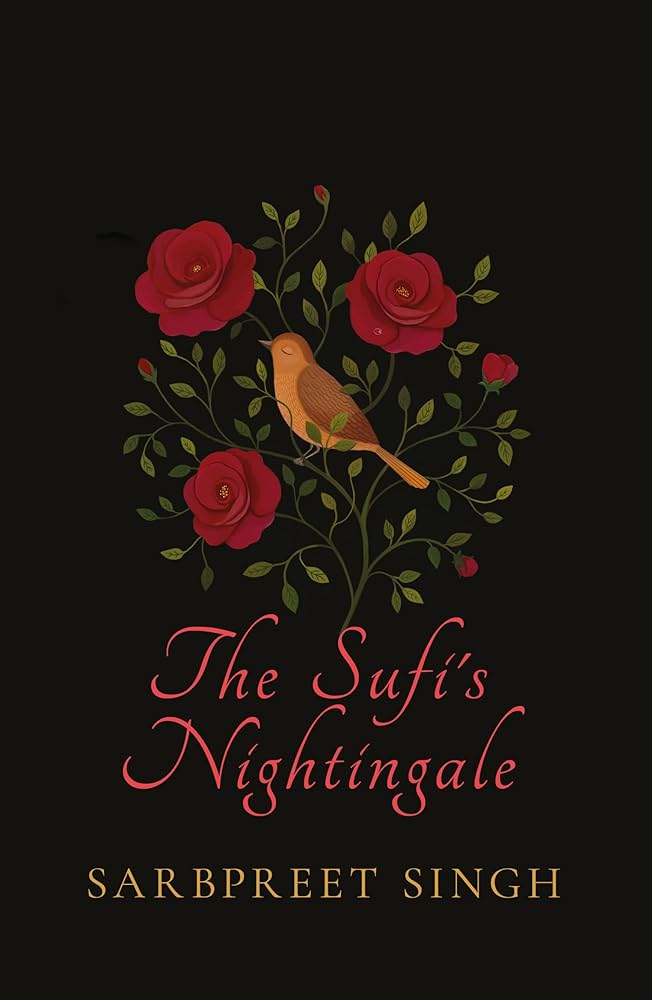

Singh’s latest work (published by Speaking Tiger Books) The Sufi’s Nightingale draws inspiration from the life and poetry of Shah Hussain, largely taking a deep dive through oral history whose results have been proclaimed as ‘writings shimmering with the pain of separation and immense love.‘ It is in all its beauty, an intricate retelling of 16th century Sufi pir-mureed, Madho Lal Hussain (jointly and affectionately called by this name).

The Sufi’s Nightingale draws inspiration from the life and poetry of Shah Hussain, largely taking a deep dive through oral history whose results have been proclaimed as ‘writings shimmering with the pain of separation and immense love.‘

Also largely set as a piece of historical fiction, it emphasises the themes of love, devotion and divine in an encompassing sense. However, there is a bit of misplacement of the understanding of same-sex love in a larger sense.

Love as a transcendental force in The Sufi’s Nightingale

The Sufi’s Nightingale follows Shah Hussain, a renowned Muslim scholar who falls in love with Madho, a Hindu boy. Moreover, the story is told through the voices of Hussain and his bulbul, Maqbool (who feels jealous of Madho). Hussain is born in a low caste Muslim family of weavers and is also a malamati – a Sufi who chooses a lifestyle that earns him rejection and abuse as a way to conquer his ego. Hussain lived during the reigns of Mughal emperors Akbar and Jahangir. The book also details how Hussain crosses paths with a Brahmin Hindu boy, Madho Lal. Lal was riding a horse from Shahdara across the river Ravi and this instantaneous moment of falling in love leads to miracles.

Having said this, there are elements which are not explored completely. The mixing of lovers of the same sex but different caste and religion is one of them but more than that, it’s the sexual nature of any relationship and where it mixes with spirituality. Shad Naved, reviewing the book for Frontline also posits a critique referring to the incident of Maqbool watching the initiation ritual – ‘At his own initiation, he realises that the acts of touching bare chests and taking a substance from the master’s mouth into one’s own are not sexual acts. Madho’s parents too fear a similar absence of differentiation when Shah Husain claims to love their son passionately.‘

Spirituality crushes queerness in The Sufi’s Nightingale

While there is a considerable body of work lying at the intersection of queerness and spirituality, there is no consensus on a definite relationship between the two (which of course varies from culture to culture and also the particular iteration within the religion in a specific context). There is a tinge of queerness in The Sufi‘s Nightingale. It is never explicit and is often shrouded under the guise of divinity as love being across all labels. There are themes of heartbreak, scandal, mystical experiences and spiritual enlightenment and they all are placed in a spiritual sense, almost as if we are worshiping love in the purest form.

And there is much substantiality to this as well. The final resting place of both Hussain and Madho are in the same mausoleum outside Lahore, akin to Jamali Kamali tomb in New Delhi’s Mehrauli Archaeological Park Complex. The former is also the space for the Mela Chiragan festival, which is largely a celebration of love and spirituality of these figures within the local community. In today’s context, their story is also among the most celebrated instances of same-sex love in pre-modern India. And The Sufi’s Nightingale feels to do justice to this radical queer history.

There is a tussle between establishing the inherent political nature of queerness which delves into the harsh reality alongside the backlash that comes from religion and or spirituality. On the other hand, so many queer people do share a spiritual connection that aids them in understanding their self and identity and they exist as queer without compromising on their spirituality. While the book is largely a historical piece, it does brims up with both the questions. It definitely provides a safe haven to those queer folks who are in touch with their spiritual side and wish to explore more. It also raises the harshest questions for those who simply cannot be saints as they deal through the everyday struggle of being queer. There is space for both the narratives and as readers, we must be able to find the delicate balance even though the work is tilted in one direction.

Unfortunately, while The Sufi’s Nightingale is a brilliant piece of historical fiction, it fails as a queer themed book entirely.

Unfortunately, while The Sufi’s Nightingale is a brilliant piece of historical fiction, it fails as a queer themed book entirely. As a queer person, I do see some queerness but while the spiritual-mystical union is fantabulous to see and unearth, the physical and sexual connection is missing from the main story entirely. There should be much more to their history, especially given when we ponder over it in a creative sense. And when there is so much power in re-reading history through imagination, such queer elements should take center stage.

Writing from history

Sarbpreet Singh has mentioned on multiple occasions that The Sufi’s Nightingale is on the transcendence of love and the triumph of love. In a wider sense, it is about love that leads more into the higher spiritual life. Given that Shah Hussain is equally loved in the Punjabi fabrics of India and Pakistan, it only adds to its beauty. In fact, Singh also discusses his visit to Shah Hussain’s dargah in Lahore and how he felt that a dividend intervention gave him permission to pursue this work.

In a public discussion which also saw the launch of Singh’s book at Bangalore International Centre, the author did contemplate a lot around the challenges of writing history. He added, ‘When we write history, who we read and what our perspective is, is fundamentally important. Though this is a work of fiction, it is deeply researched. I don’t ignore Western scholarship, but my goal has been to uncover traditional texts and Janamsakhis or birth stories built on Sikh oral tradition.‘ In the book also, it is mentioned that one of the intentions of the author is for readers to seek out the original kafis of Shah Hussain.

As is it with translations, there is a difficulty to capture the essence of the original language, in this case Punjabi. Having said that, poetry and some elements of spirituality make it even more difficult. To aid the readers in navigating this space, Singh has also provided first lines of some of the original Punjabi kafis in the author’s note, which is always helpful for first time readers like me. Additionally, the work is grounded in history which adds to its charm. The encounters with Akbar or Guru Arjan (the fifth Skih Guru) and the references to Ras Khan who was a devotee to Krishna adds to the 16th century context. But that isn’t all as the creative imagination element does add more to the existing story, most notably, the character of Maqbool.

.Sarbpreet Singh’s The Sufi’s Nightingale is a glowing piece of historical fiction which almost falls into the category of hagiography.

Sarbpreet Singh’s The Sufi’s Nightingale is a glowing piece of historical fiction which almost falls into the category of hagiography. A beautifully crafted tale of love and spirituality, the book fails as a queer book that deals with one of the first instances of same-sex love in pre-modern India and Pakistan. There is much offered in the book about love in its purest form but the lackluster exploration of the queer component of love takes away the bulk of its charm. From a lens of historical fiction, it stands on its own defiantly. Disappointingly, as a historical novel that takes away erotic love from spiritual love, it doesn’t do justice to its remarkable queer history.