Back in September, I found myself in a workshop being organized for teachers across Delhi NCR. In her introduction, the facilitator brought up the story “Perfume Teacher”, which in its original form, briefly goes like this: A student, initially unpopular with his teacher due to his inattentiveness and poor academic performance, ultimately led the teacher to realize that teaching goes beyond just imparting skills, and towards nurturing students. This revelation came when the teacher received an old perfume and bracelet as Christmas gifts from the student, and she learned that these items once belonged to the student’s deceased mother. This moment, where the student saw the teacher as a mother figure, brought tears to her eyes and led to her understanding that teaching encompasses more than just skills transfer.

During the workshop, the discussion shifted towards the idea that the teacher’s love and care for the student had inspired this meaningful gift exchange, ultimately defining her as an exceptional educator. The facilitator then posed the question: “Do you aspire to be ordinary teachers or “perfume teachers”? Most teachers expressed a preference for the latter. In this context, I found myself wondering whether I, too, wanted to take on a maternal role with my students and whether this nurturing aspect was integral to my teaching practice.

Terms blurring boundaries between kinship and the teaching profession

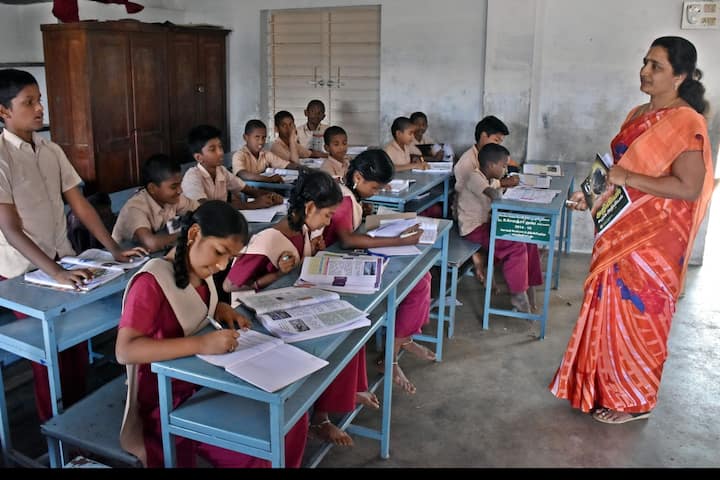

As I pondered over this question, I recalled that some educators introduced themselves as “mother-teachers,” a term that caught my attention. Upon further inquiry, I learned that in certain schools, this term is used to describe teachers who instruct at the primary levels. The rationale behind this term is that at this educational stage, teachers are responsible for teaching all subjects while considering the emotional, cognitive, and social aspects of a child’s development.

Consequently, they are not merely professionals but also substitute mothers within the school environment. This implies an essentialisation of qualities such as care, empathy, and maternal attributes, particularly among female teachers. This role also entails a significant amount of “emotional work”, which according to Sociologist Arlie Hochschild refers to the effort expended by individuals to modify and heighten their emotions while simultaneously suppressing undesirable feelings.

During my relatively brief teaching career, I encountered another term that blurs the boundaries between kinship and teacher roles: “house parent.” This term is used to refer to individuals responsible for the care of students in hostels. The prevailing understanding and expectation are that, given the students’ residence in a hostel, these house parents effectively function as surrogate family figures. This sort of terminology can be juxtaposed to a remark by a college professor who questioned why all relationships had to be framed within the context of kinship. She brought up the question of whether it would suffice for individuals to be acknowledged solely as teachers and students, without the added dimension of a familial association.

While I understand the relevance of having these terms and expectations for ensuring the comfort and wellbeing of students, I am left wondering about the well-being of teachers who have to take on these roles

While I understand the relevance of having these terms and expectations for ensuring the comfort and wellbeing of students, I am left wondering about the well-being of teachers who have to take on these roles. Is there training provided to them for the care centered tasks they are expected to carry out? Do they ever find support, or are they always only supposed to provide it? Would students be equal stakeholders in this equation and reciprocate? Who is acknowledging and returning this caring attitude that teachers are constantly expected to provide?

Attributes of an ideal teacher

In addition to the academic pursuits, teachers are expected to be approachable, available, kind, caring, to put thought into each and every lesson, to look at overall development of students and so on. These are qualities that are expected to come naturally to teachers, perhaps by virtue of the profession being largely composed of women. In order to carry out these tasks, to communicate these feelings, teachers often have to engage in “deep acting” which is an aspect of emotional labour, as Hochschild would say.

Hochschild utilises the insights of theater practitioner Stanislavski to delineate the distinction between “surface acting” and “deep acting”. Stanislavski is renowned as the creator of “method acting,” which demands that actors immerse themselves so deeply in their characters that they cease to act and instead react in a manner true to the character’s nature. In surface acting, performers simulate the character’s persona primarily for the audience’s benefit.

On the other hand, in method acting, also known as deep acting, actors become so absorbed in their characters that the audience becomes almost secondary; during the play’s duration, the actor essentially becomes the character. Hochschild delves into the core of this concept with the notion of deep acting. In deep acting, emotions or feelings are internally generated so much so that the manipulated emotion is authentically generated.

In addition to the academic pursuits, teachers are expected to be approachable, available, kind, caring, to put thought into each and every lesson, to look at overall development of students and so on

In practice, although the general expectation is for teachers to deeply engage with their emotions, this isn’t consistently the reality. Some teachers may resist this and opt for “surface acting,” which involves managing their outward expressions rather than delving into internal emotional dialogues and justifications.

Teaching and compensation

Teaching comes under the professions that are not labeled as jobs, but rather as “callings”. Individuals are expected to pursue this profession with the intention of making a positive impact on the world, and it’s commonly believed that financial gain is not the primary motivator for engaging in this field.

Teachers’ work is impossible to complete within working hours, hence tasks like lesson preparation and checking are often carried home and completed outside working hours. A seven-hour job on paper is seldom just that. Does it being a calling imply that teachers need not be paid as much is due to them? The hard tasks, as well as the emotional work involved are often veiled behind the garb of love, maternal instincts and calling.

While I am questioning the need to include teaching within the ambit of “care work”, there are scholars who accept and theorize it as such. Sociologist Paula England is a relevant figure to include in this conversation, as she draws upon various theories to conceptualize the perception and compensation of care work. One is the “devaluation” perspective which posits that care work is inadequately rewarded due to its association with women. Another is the “public good” framework which emphasizes that care work generates benefits that extend well beyond the direct recipient and suggests that the low wages for care work represent an instance of market failure in adequately valuing public goods. In contrast, the “prisoner of love” framework argues that motivations of care workers come intrinsically, and this makes it easier for employers to justify underpayment.

Is the path forward to depart from the perspective that teaching is inherently tied to care work and kinship dynamics?

If seen from these points of view, we can understand why there is insufficient compensation for the profession of teaching. Is the path forward to depart from the perspective that teaching is inherently tied to care work and kinship dynamics? Should we instead acknowledge, respect and duly compensate it as a category of care work, and by doing so, extend this recognition to other types of care work? Or should we strive to find a way to reconcile these two viewpoints?

In this journey through the field of teaching, this piece has explored the blurred lines between education and care, the emotional work of educators, and the question of fair compensation. The profession’s evolving expectations prompt us to reflect on what it means to be a teacher today and challenge us to find a balance that respects the caring nature of the role while ensuring educators receive the recognition and compensation they deserve.

Further reading:

- https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/13293_Chapter4_Web_Byte_Arlie_Russell_Hochschild.pdf

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/29737725

About the author(s)

Shambhavi has a Master's in Sociology and is an educator and dancer who enjoys writing in her free time. She writes about culture, education, gender and cinema, and likes incorporating theory with her everyday observations.