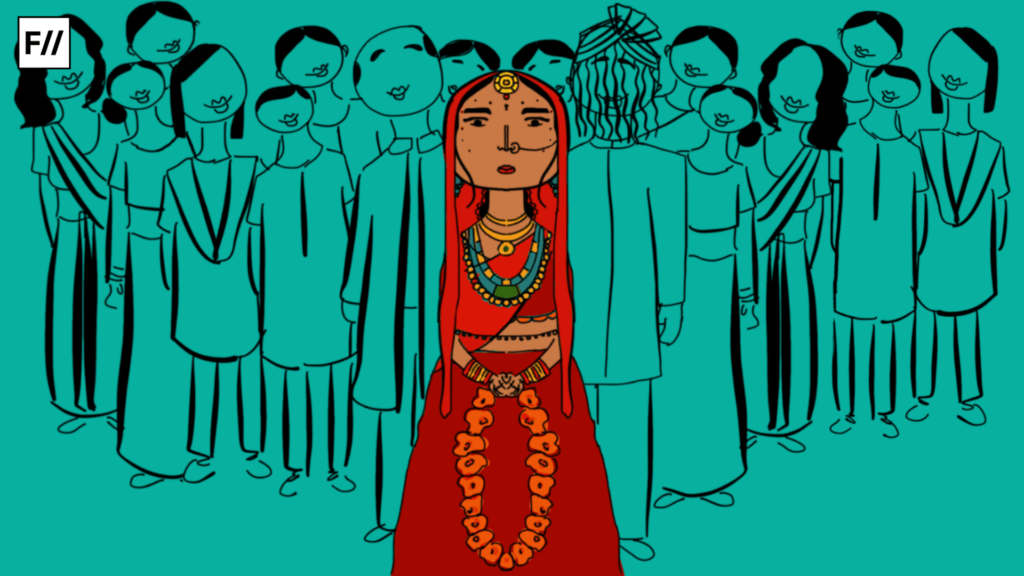

The manifestos, from smaller political parties to the larger political parties for the Rajasthan Assembly elections in 2023, had no place for the dire issue of the dowry system.

This age-old tradition has tragically transformed into a curse for women across the state of Rajasthan. It occurs that political leaders are dismissing the gravity of this deeply rooted issue. They audaciously label it as insignificant, claiming that it depends solely on an individual’s financial capacity. Their callous assertion implies that those who possess the means will partake in this system, while those who lack financial resources will abstain.

The haunting reality, however, is that the dowry system continues to plague countless women, casting a shadow over their lives. But for these leaders, addressing this social malaise seems to have become tedious and uninteresting. The suffering and struggles faced by numerous poor women due to this practice seem to fall on deaf ears.

This malice practice of dowry is all the more concerning in the Mewat region, which serves as a connecting link between Haryana and the Rajasthan border. Despite the adverse impact on the lives of women, the normalisation of this practice persists, rendering it a dishearteningly ordinary affair.

This is the story of every shelter where any girl lives.

In her late 20s, Akbari, living in Pahadi village in Rajasthan’s Mewat, like many other thousands of women, has lost hope that she will ever get any justice. She is illiterate but excels in various household chores, from cooking to tailoring suits. She knows Arabic and Urdu, along with her local language, “Mewati.” She has been living with her 5-year-old girl child at her mother’s home for the last five years. She is not divorced because her husband refuses to grant her one, yet he has remarried.

Her ordeal began on November 6, just two days before the demonetisation in 2016, when she married and moved in with her husband and his family—the people who made her life hell for the next two years. She faced relentless abuse, enduring daily beatings because she bought an Alto car instead of a Swift Desire or a Bolero. She was forced to live in a locked room because she failed to ask for more money from her parents to give her husband and his family.

She explained that her life was in jeopardy at her husband’s home. ‘When my family members arrived at my husband’s home to take me back, they refused and explicitly stated they wouldn’t release me. They continued to assault me every day, citing their dissatisfaction with the dowry. Consequently, my family lodged a complaint at the Chandigarh-based police station. The police then intervened and brought me back from my husband’s home. If the police hadn’t rescued me from those people, I dreaded thinking about what might have become of me by now. They seized all my jewellery and didn’t allow me to take any of my essential things, not even my clothes,’ Akbari told FII.

‘When I returned home, my condition was extremely dire,’ she said with a heavy heart.

Her mother, who did wish to be unanimous, in her late 60s, with tearful eyes, said, ‘My daughter, though illiterate, lacked nothing in any aspect; she is skilled in every task. We fulfilled every possible demand to the best of our ability. Whatever we had, we gave it all, even during the tumultuous period of demonetisation when our financial situation was dire and we barely had any money. Yet, even after that, they treated our daughter so poorly.’

While talking about her husband, Akbari said that he remarried another woman, but she will not enter into another marriage ever.

‘I cannot place my trust in any man now. If the first one didn’t remain truthful, how can I expect the next one to be honest? I will live with my daughter. She is my reason for living now, and I exist solely for her,’ Akbari said further.

Normalising dowry practice

The dowry system has become a pervasive issue in our society, despite being a severe problem.

FII also reached out to Waseem Akram, who works as an engineer but dedicates his time to being a social activist and reporter. He felt compelled to pick up the mic for Mewat when he realised that the multitude of social issues prevalent there needed immediate attention. Witnessing this void, he made a conscious decision to work as both a reporter and a social activist, along with his job of engineering, aiming to shed light on the pressing concerns within his region.

Akram stands out as the individual who initially reported on the Nasir-Junaid murder in Haryana. His dedication led him to assist journalists visiting Rajasthan to cover the harrowing incident of Junaid and Nasir’s brutal killing, aiding them in comprehensively covering this tragic event.

While discussing this malice practice of the dowry system, Akram said that the dowry practice has become so pervasive that it appears impossible for a girl to get married without giving the groom a dowry. ‘Regretfully, our state’s political leaders do not see this as a serious problem. As a social activist, I have repeatedly failed in our attempts to bring political leaders’ attention to this pressing issue through social media campaigns, rallies, and other means.’

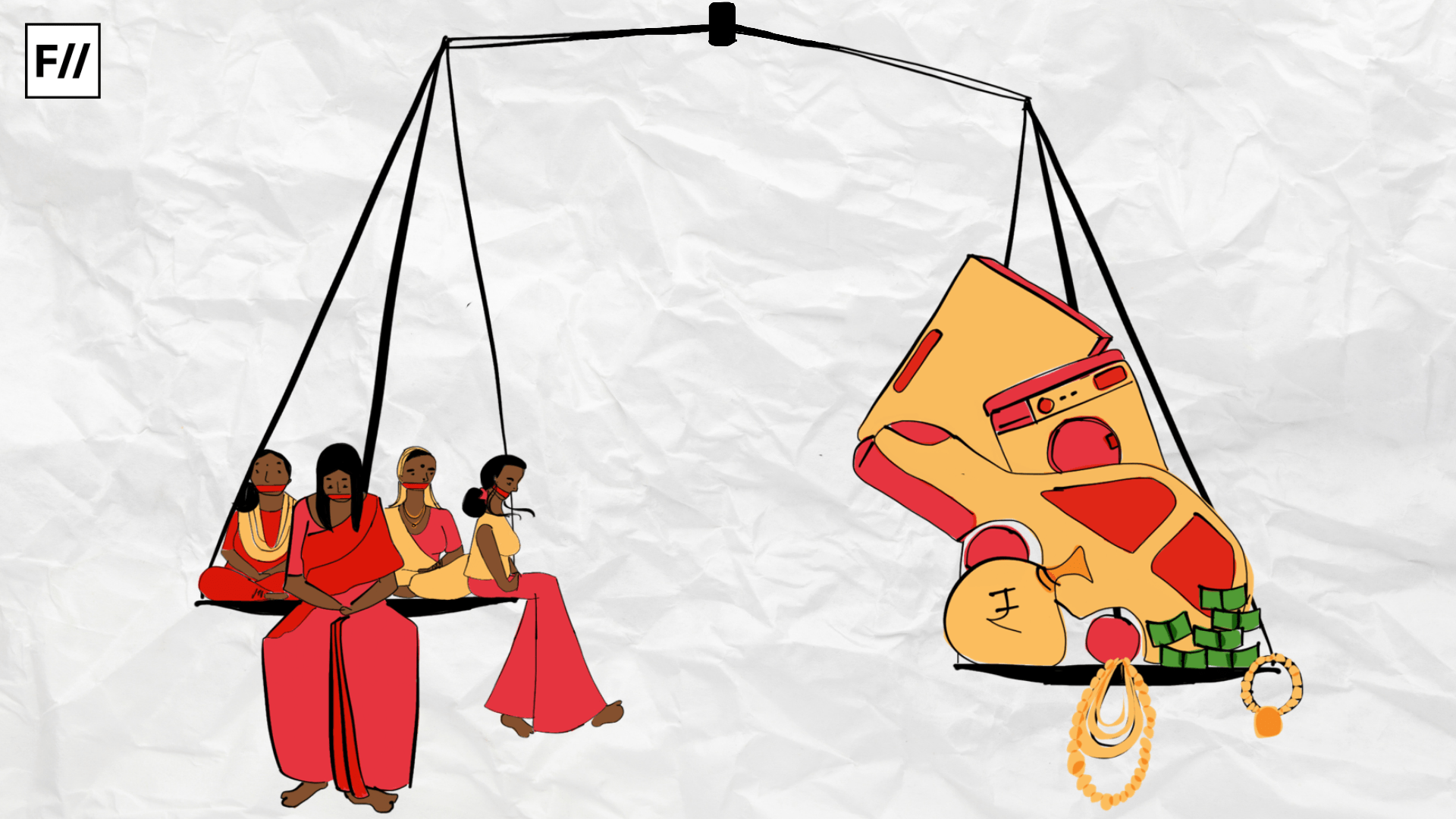

While discussing how this harmful practice impacts not just the bride but the entire community in various ways, Akram deeply explained that this practice directly affects not only the bride’s family but also the groom’s family. In marriages, both sides spend money. If the bride’s family is giving jewellery to the groom’s family, then the groom’s family also gives something to the bride, although it might be comparatively less than the expenses incurred by the bride’s family. However, they also bear some expenses.

Straining families, curtailing education and ignoring evils

According to Akram, this practice financially weakens families, and the most significant impact is the lack of education. Parents refrain from providing education to their girls because they fear that if they invest in their education, they won’t be able to gather enough dowry for them during their marriage. Parents continuously focus on accumulating dowry for their daughters, neglecting their education.

In villages, people are not wealthy enough to educate their daughters and provide dowry simultaneously. They opt to prioritise dowry over education, leaving the girls uneducated. The less educated a girl is, the more dowry is demanded. However, this understanding is not grasped by anyone here (in Mewat) due to narrow-mindedness, backwardness, and illiteracy.

Akram emphasized the urgent need for a stringent law against the dowry system to prevent the ruin of many women’s lives and to curb numerous suicides. According to him, the government is looking at women’s issues from the wrong perspective and should seriously work towards abolishing the dowry system instead.

Rajasthan is one of the states in India that has witnessed a concerning number of dowry-related deaths and violence. Rajasthan reported a total of 2,244 dowry deaths, according to data provided by the Union Home Ministry in response to Parliament, between 2017 and 2021.

Over the five years, Uttar Pradesh recorded the greatest number of dowry deaths (11,874), followed by Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Bengal, and Rajasthan.

Between 2017 and 2021, 5,354 women in Bihar lost their lives as dowries, accounting for more than 1,000 deaths annually. The average annual death toll in Uttar Pradesh is 2,375. In five years, there were 2,859 dowry deaths in Madhya Pradesh, 2,389 in West Bengal, and 2244 in Rajasthan.

The dowry system became a topic of discussion in 2022 after three sisters and their children were found dead in a well in the state of Rajasthan. Before their deaths, they left a note accusing their husbands’ family of being to blame for their plight.

Kalu, Kamlesh, and Mamta Meena became victims of the evil of the dowry system last year.

For a while, the media highlighted this issue, but eventually, it seemed to disappear from newspapers and channels as if the matter no longer held any importance in society.

“Dahej Hatao, Beti Bachao“

We also approached an international Taekwondo medalist, a social activist, and a Congress leader Rajia Bano from Haryana’s Mewat region to discuss the insensitive issue of the dowry system.

She is working to eliminate this practice. Last year, in 2022, she organised a rally titled “Dahej Hatao, Beti Bachao,” across the Mewat region of Haryana. Unfortunately, this rally only had about a 1-2 per cent impact on people’s minds regarding the dowry practice.

However, the title of this rally has now become a campaign for her in the fight against the dowry system. She is establishing a team in the face of an NGO that will work against the dowry system. She said, ‘I am establishing a team that will fight against this evil named dowry because I cannot fight alone. I need people’s support to wage this battle. Our agenda with this slogan, “Dahej Hatao, Beti Bachao,” is to free girls from this dowry practice.’

While discussing approaches to ending this practice, she stressed the importance of education. Bano agreed that education serves as a powerful weapon to protect girls and the entire society from the detrimental practice of dowry in the Mewat region.

She said, ‘Whenever I come to know that a family is demanding dowry, I make it a point to visit and explain to them the drawbacks of dowry. I talk to the parents of girls, emphasising how crucial education is for their daughters. I strongly encourage them to prioritise educating their daughters.’

Educational backwardness fuels dowry

Mewat is the most backward region in the country, whether it is Haryana’s Mewat or Rajasthan’s Mewat. Both are the same in their backwardness because of a lack of education, Bano emphasised.

Mewat has one of the lowest rates of literacy in the nation. The average literacy rate was 54.08 per cent, according to the 2011 census. With men at 69.94 per cent and women trailing behind at 36.6 per cent, there is a notable gender gap.

Rajasthan, the state encompassing Mewat, has also reported the country’s lowest literacy rate for women, standing at 57.6 per cent.

According to the National Statistical Office (NSO) report, Rajasthan’s overall literacy rate stands at 69.7 per cent, marking it as the second worst in the country, after the state of Andhra Pradesh at 66.4 per cent.

According to the report, 43.7 per cent of women who are five years of age or older have never attended an educational institution or received any kind of formal education.

This data highlights that Rajasthan is among the states with the worst educational outcomes for girls.

The lack of education contributes to the poor practice of the dowry system. When we tried to approach other girls who were also the victims of dowry, they refused to discuss the issue with us. And all of them, like Akbari, were illiterate.

Now, Akbari believes in the power of education. She wants to educate her daughter. However, she doesn’t know how far she will be able to educate her or what she will become. But one thing she knows for sure is that she won’t let her daughter remain illiterate like herself.

When we asked Akbari’s mother why she didn’t provide education to her daughter, she replied, ‘We, as zamindar (landowners), don’t educate our daughters. It wasn’t our tradition to educate our daughters. But now, we regret not educating our daughter; we wish we had educated her and empowered her to stand on her own feet.’

I am also a blogger and write about women oriented issues .

But your blogs are well structured and the topic is very heart touching.