Feluda!

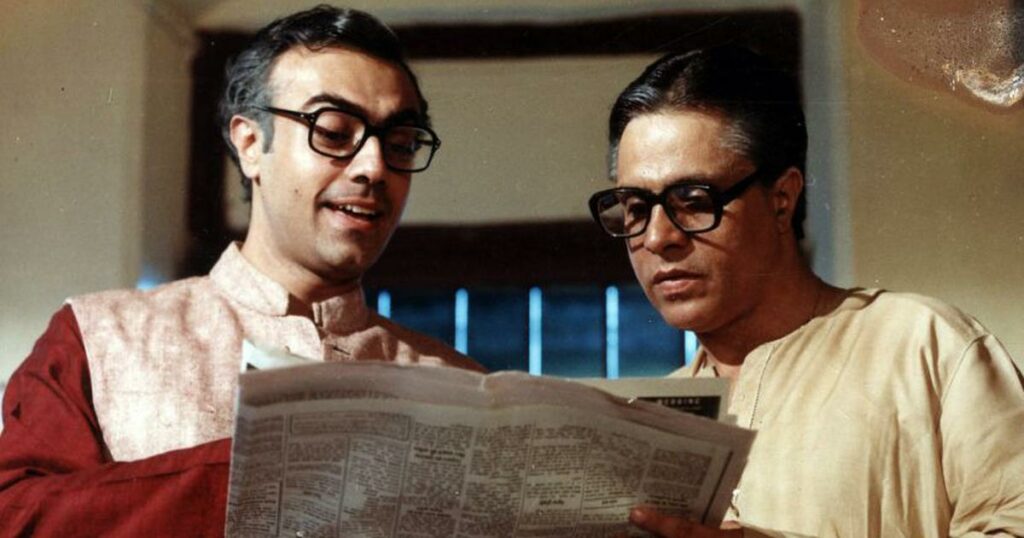

The very name instantly evokes a sense of cosy nostalgia, fuelled by a deep-seated familiarity of the adrenaline-driven, essentially pure ethos of a particular iconic trio in Bengali literature. One would hardly find any literate, middle-class Bengali household where every member of the family hasn’t grown up, or at least, spent their early adolescence, pouring over the adventures of Ray’s inimitable detective, his satellite Topshe, and the celebrated thriller writer, Lalmohan Ganguly, alias Jatayu.

Establishing the Feluda universe

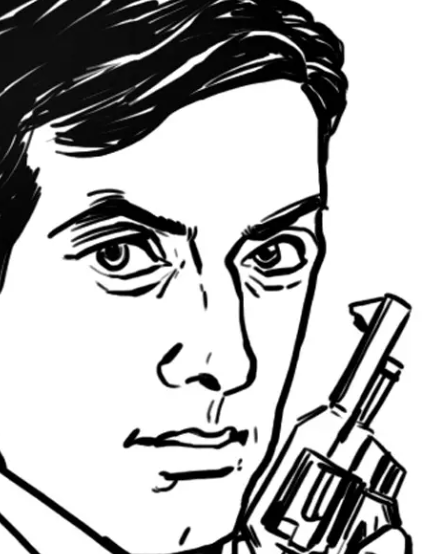

Feluda, or Prodosh C. Mitter, stands tall at 6 feet, is fitness conscious, and athletic, a fact reiterated by the many times he gets the better of hired guns who make the mistake of attacking him or his associates. He wields a pistol when need be, but often manages to put dangerous men behind bars simply by wielding his mogojastro, or activating what yet another extraordinary literary sleuth of Belgian descent would call “his little grey cells.”

Feluda is also quite dashingly handsome, what with his chiselled cheekbones, as highlighted in the numerous illustrations of the detective by Ray himself. Over the decades, the various adventures through which the brilliant detective distinguished himself time and again have been brought to life across film and television, most prominently by Ray himself, followed by others after him.

The women, or the lack thereof

And yet, staggeringly, this beloved literary universe of one of Bengal’s most cherished fictional characters is starkly devoid of female presence. Women appear so peripherally, if at all, that even the most ardent fans would have to wrack their brains to come up with names, or instances, of female characters in these novels.

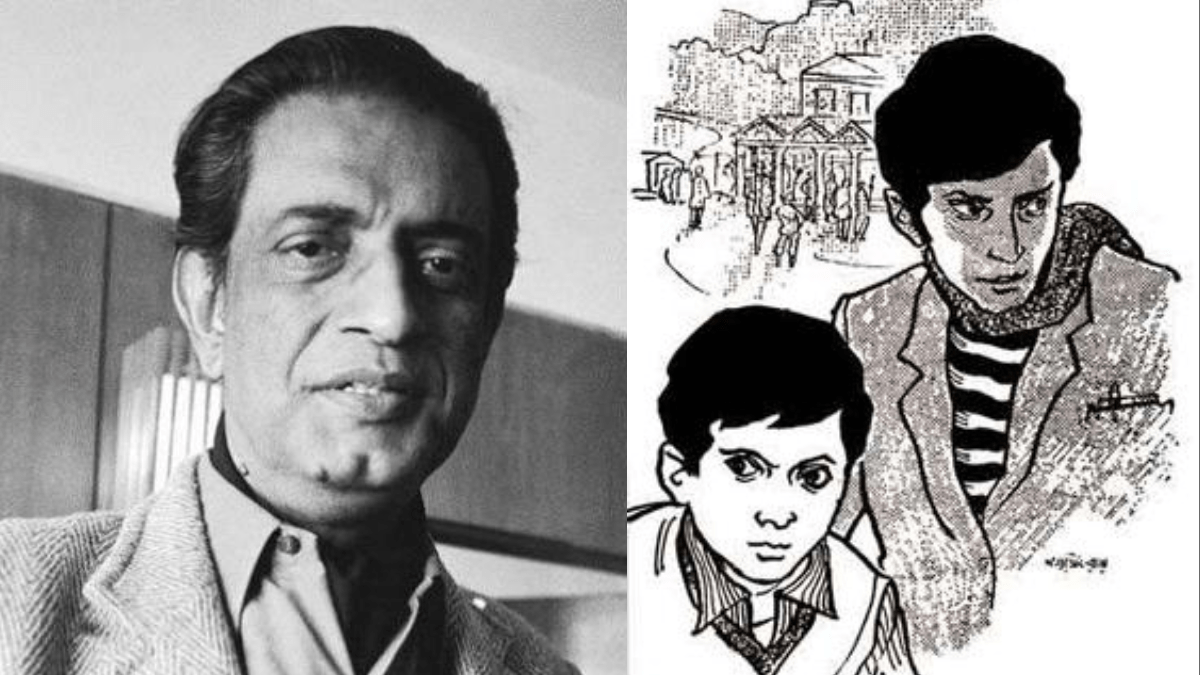

A master of his craft, Satyajit Ray’s films portrayed and delved into the woman’s psyche with uncommon insight and sensitivity, but the author Ray seemed to purposely stay away from women, thus inevitably problematising female representation in his novels.

It is widely believed that Ray himself implicitly addressed his conscious decision to shun women in his stories by pointing out their young adult readership, which necessitated a sort of prepubescent innocence. “…the stories have to be kept ‘clean.’ No illicit love, no crime of passion…” he wrote in 1988. This statement, if anything, is more controversial than the problem itself.

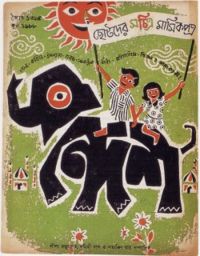

Does female presence inevitably convert a text from ‘clean,’ to ‘unclean?’ Would the young readers of the now classic children’s magazine “Sandesh,” where several of the stories were published, have magically lost the child in them if a woman were to step foot inside 21, Rajani Sen Road—the sleuth’s celebrated address—say, as a client? More pertinently, does female representation inevitably imply an inherent sexualisation, irrespective of genre?

The legacy of Conan Doyle & Saradindu

For some noted writers of crime fiction, it did. The other famous fictional detective, nay, truth-seeker, in Bengali literature, is the eponymous Byomkesh Bakshi; probably the only married man of his kind. Complete with a wife and son, he represents the proverbial bangali bhadralok; what makes him stand out are his razor-sharp intellect and analytical powers. Now, while Satyabati, Byomkesh’s wife, is only sparsely mentioned after her initial introduction, the stories, though, are riddled with female characters of varying importance.

Yet, what’s relevant here is that the female presence is at once permeated with a sense of stark sensuality, and met and unmet desires that come together to conjure the often dark, even sordid, backdrop of the stories. Women are often ignored, and at other times sexualised, in Bakshi’s complex, layered, but ultimately androcentric, universe.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the ultimate fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, from whom Byomkesh’s creator, Saradindu Bandopadhay, seemed to have drawn inspiration, treated women somewhat similarly in his novels, although not entirely.

Female characters littered the stories, mostly as clients, sometimes as housekeepers, as in the case of Mrs. Hudson, or as wives, as in the case of Mary Watson, but hardly ever became pivotal to the plot. Yet, there was one exception to this rule in the form of Irene Adler, who was one of the few to have ever outwitted Holmes, and whom Holmes himself referred to as “the woman,” implying something akin to humility.

In Ray’s novels, there was no Irene Adler. Feluda never had a female client, and the closest Ray came to assigning significance to a woman was in Dr. Munshir Diary (Dr. Munshi’s Diary), where the doctor’s wife; the only femme fatale in the Feluda stories; was revealed to have plotted her husband’s murder having urged her brother to go for the kill, quite literally.

Aside from this, Mary Sheila in a lesser-known story called Shakuntalar Kanthahaar (Shakuntala’s Necklace) played a vital role in the course of events. But curiously enough, even these two women, despite their prominence in the plot, appeared only peripherally in the actual text.

Apart from this, Nilima in Chhinomostar Abhishaap (The Curse of the Goddess), and a few other scattered characters like Ambar Sen’s unnamed sister-in-law in Ambar Sen Antardhan Rahasya (The Disappearance of Ambar Sen), the young girl, Leena, in Bosepukure Khunkharapi (The Acharya Murder Case), and the elderly grandmother in Jahangirer Swarnamudra (The Gold Coins of Jahangir) who inadvertently offers Feluda a major clue, more or less constitute the entire body of the female character in the Feluda universe.

Female vs male writers

What’s interesting is that women writers of crime fiction have treated women a tad differently in their texts. It’s impossible not to delve into the works of the queen of the genre, Agatha Christie, while on this subject. And even more impossible not to discuss the phenomenal Miss Marple, one of the most incredible detectives in the history of crime fiction.

Christie’s Miss Marple, often overshadowed by her popular male counterpart, Monsieur Hercule Poirot, was a kind of antithesis to the supremely male-dominated world of the amateur investigator. Jane Marple, initially introduced as something of a fussy old maid, reveals herself by and by to be sharply observant, and a shrewd, intuitive student of human psychology. She cracks case after case, much to the utter astonishment of the police detectives involved, because after all, who expects an elderly spinster to have deductive powers or even brains?

While Marple is one of a kind, women in general feature heavily across Christie’s stories, whether novels or short stories. From being the protagonists of their adventures, like Anne in The Man in the Brown Suit, or Frankie in Why Didn’t They Ask Evans, to masterminding crimes, like Jackie in Death on the Nile, or perpetrating them on numerous occasions, women folk were smart, intelligent, and autonomous, with agency of their own.

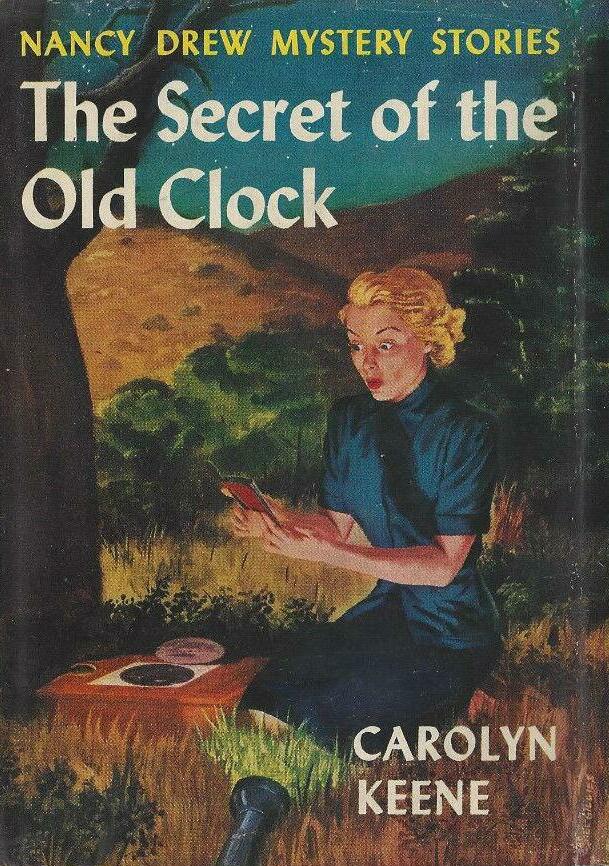

The adventures of the spirited teen detective, Nancy Drew, are yet another interesting example here. Although written over the decades by a series of ghostwriters under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene, the detective was created by what turned out to be the first of the Keenes, Mildred Benson, a female journalist-writer.

Closer home, eminent author Suchitra Bhattacharya, known for diving deep into the multitudinous facets of the woman in her novels, created the only female detective in Bengali literature so far. Mitin, or Pragyaparamita Mukherjee, is a private eye who runs her detective agency and is often assisted on her cases by her teenage niece, Tupur. Mitin is a competent cook, a wife, a mother, as well as a successful detective, thus making her an accomplished modern woman in every sense.

Women, therefore, can play major roles, sometimes the most important ones, in detective stories without being sexualised or relegated to non-existence or minor roles. It is, perhaps, all a matter of perspective.

The complex role of the male gaze in crime fiction

The dismissal of, and discrimination against, female characters by male authors of crime fiction might be interpreted, somewhat tangentially, by Laura Mulvey’s acclaimed notion of the “male gaze.” Women are reduced to being sexual objects by male viewers who represent the heterosexual man for whom a woman is essentially nothing more than her body.

Mulvey’s thesis finds its premise within the film text, but can as easily be applied to literary texts. Just as the heterosexual male views the woman as an object of desire through the lens of the camera, the male author wields his pen to diminish women for the sake of the male reader. It is, at the end of the day, the manifestation of a deep-rooted phallocentrism that the author may not even be conscious of.

One may conclude that Ray inherited the legacy of Conan Doyle and Saradindu, and even before them, of Edgar Allen Poe, who created the character of C. Auguste Dupin, in the first ever detective story as early as 1841.

But just as Holmes’ sister, Enola, surfaced in the new millennium, perhaps to correct the nigh-absence of women in the Holmsian universe, one could hopefully still come up with newer adaptations of the hitherto de-sexed Feluda series in decades to come with women who can challenge the detective’s formidable intellect and give him a run for his money.