One of the earliest works to come out of feminist film theory investigating relations between feminism and cinema was Laura Mulvey’s epochal 1975 essay, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. Films are not merely part of our everyday popular culture, they play an important role in the politics of representation, depiction and portrayal of women in the society. Feminist film theory gives us a perspective to look at films through a feminist lens. It assists us in critically analysing who, what, how and when women are constructed/ depicted on the screen.

In this context it is important to reflect on Laura Mulvey’s work. Mulvey in her essay argues that a film should not merely be seen as a text or a work of art, rather we should critically look at cinema as a political tool and evaluate how a film is made, who produces and directs it, and how it represents what it intends to represent. She uses the framework of psychoanalysis to ‘discover where and how the fascination of film is reinforced by pre-existing patterns of fascination already at work within the individual subject and the social formations that are at work’ (Mulvey, 1975, p. 6). that are at work.

In the section ‘Women as Image, Man as Bearer of the Look’, Mulvey writes:

‘In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly’ (Mulvey, 1975, p. 11).

In her analysis, Mulvey demonstrates how patriarchy unconsciously shapes both production and consumption of cinema.

In her analysis, Mulvey demonstrates how patriarchy unconsciously shapes both production and consumption of cinema. Despite the subsequent criticism of Mulvey’s essay for its phallocentric outlook and one-way focus on male gaze, her work has played a significant role in understanding the intersection of gender and popular culture and in the overall feminist historiography.

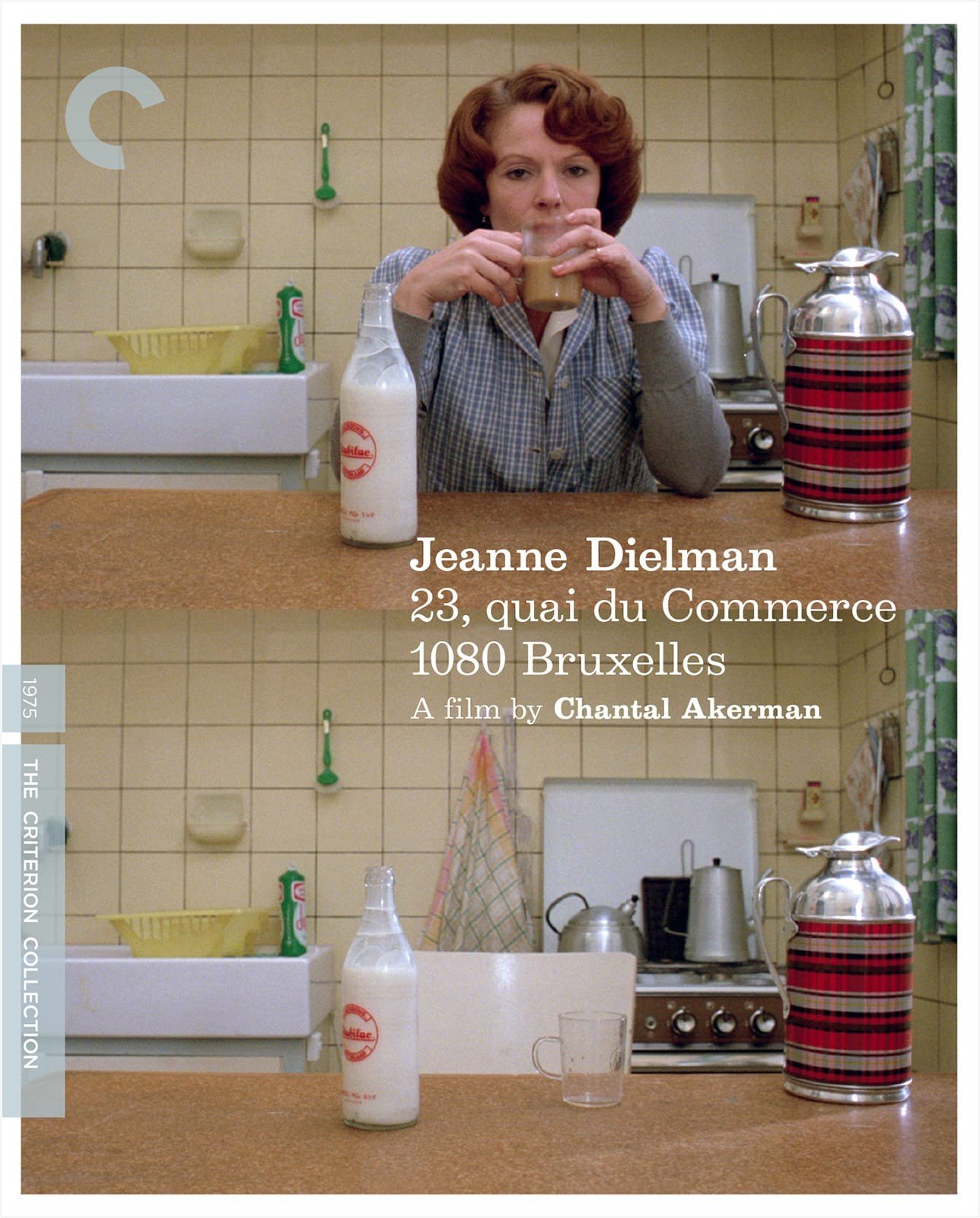

In this context, we shall analyse the intersection of feminism, gender, and popular culture in Chantal Akerman’s film Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) from Belgium.

Understanding Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

It is difficult to give a descriptive account of what the film Jeanne Dielman wants to convey. It is a film about the daily mundane routine of a middle-aged widow whose life revolves around ordinary chores such as making the bed, shopping for food, cooking a meal for her son, washing the utensils, taking a bath, cleaning her bathtub, etc. Sleeping with different men for money is also one such daily habit in Jeanne’s life. The film depicts three days in the life of Jeanne doing these repetitive tasks that fill her empty life and help maintain her sanity (Kinder, 1977, p. 3). Jeanne’s life is dictated by order and routine. One day out of the ordinary, Jeanne’s routine gets altered, ‘she wakes up early, she misbuttons her robe, she drops a spoon, she makes the coffee too strong, she leaves soap on one of her plates, she can’t match a button, she leaves a pair of scissors out of place. These minor deviations are combined with too many unsettling surprises: a stamp machine is empty, she receives a disappointing birthday gift, she is rejected by a crying infant. As a result of these disruptions, she has an orgasm and commits a murder’ (Kinder, 1977, p. 4).

Nothing happens: mundanity as a political act

‘The film explores the relationship between identity and action. If a woman is what she does, then why is it that movies never show us the thousands of familiar moves that comprise a woman’s life? Trapped in the passive roles defined by the culture, women perform actions that are considered boring and non-dramatic – except for having sex, giving birth, or going mad’ (Kinder, 1977, p. 4). Women are either passive sex objects and damsels in distress in male-dominated action films, or they are victims or maniacs, mothers or sex workers.

Jeanne is all of these things, but her actions and roles do not adequately or completely define her. A more conventional film would have focused on Jeanne primarily as a murderer or sex worker, but Akerman’s structure prevents us from doing so. We are forced to consider all of the details that are normally omitted from films in order to understand and judge her as a human being, because it is precisely these banalities that explain her desperation and violence (Kinder, 1977, p. 4).

A more conventional film would have focused on Jeanne primarily as a murderer or sex worker, but Akerman’s structure prevents us from doing so.

‘Time and space, the two mental constructs by which humans organize experience, are treated unconventionally in the movie’ (Kinder, 1977, p. 4). Majority of the scenes are captured in real time, giving a documentary kind of feeling. This forces the viewer to sink in the film and questions the conventional idea and rationale of film watching. After all, the traditional 90 minute cinema is supposed to provide us with entertainment, but we tend to forget that the entertainment that we crave for is steeped in the political representation of gender binaries, which reinforces gender norms, roles, and stereotypes. Ackerman, in an innovative manner, breaks this convention.

‘Akerman’s unconventional style expresses a feminine perspective and sensibility. More than any other filmmaker, she makes us realize how previous films have been almost totally restricted to a male point of view. Despite the limitations of her character, Jeanne, Akerman, and her female crew provide a radical feminine perspective that enriches our perception of the world’ (Kinder, 1977, p. 2). The meticulously detailed nature of the film breaks the often regularised assumptions of particular scenes in both film-making and watching.

Consider a scene depicting Jeanne taking a bath before her meal; we see more than a few sexual glances of flesh in the water; we see Jeanne performing the mundane and the everyday act of scrubbing every part of her body and then cleaning out the tub. The fine details of the scene undermine and subvert the eroticism and emphasise how artificial and contrived most other bath scenes are. ‘Because of the utilization of real time, we are forced to consider how many steps are involved in each simple action’ (Kinder, 1977, p. 4).

Depiction of reproductive ‘invisible’ labor

One more crucial element of the film is its depiction of reproductive labor; lengthy and extended shots of Jeanne’s monotonous and dull daily household tasks are interspersed with passing sex scenes, which are never shown except in the last portion of the film. It is important to note that ‘In the case of housework, Jeanne sells her labor power for an indeterminate period of time, whereas in the case of prostitution, she sells her labor power for a determinate time. It is through the deployment of an extended temporality in the scenes of domestic chores, then, that estrangement is experienced, exposing Jeanne’s “unbearable alienation from her labor power.”’ (Sequeira Brás, 2019, p. 5).

The cinematic technique of using real time for her household labor to focus on the indefinite amounts of time women put in at home to serve their families demonstrates how, due to its repetitive, exhausting, and never-ending nature, household labor becomes invisible and is not recognised as work that should be seen and rewarded. Rather, it is taken for granted and gains a foucauldian commonsensical understanding in the society; something which is an inherent and ordained duty of a specific gender which does not merit discussion.

Jeanne is shown becoming careless about the accuracy with which she handles her daily tasks over time, and her exhaustion from the relentless repetition of her labor becomes apparent.

It is important to note here that Akerman deliberately gives less screen time to show the sexual labor that Jeanne undergoes, which is a paid form of work. Jeanne is shown becoming careless about the accuracy with which she handles her daily tasks over time, and her exhaustion from the relentless repetition of her labor becomes apparent. She murders her client with a pair of scissors, putting an end to the vicious laborious cycle that has come to mark her life.

The capitalist mode of production which forms the bedrock of our economy is based on the premise where certain forms of labor are paid and accounted for while all other forms are considered unproductive and are merely seen to help able-bodied men fulfill their ambitions and lead a productive, profitable life. Women’s labor in public places is viewed as an extension of their household labor and is intended only as a supplement, not as a primary source of income.

Jeanne breaks free of the structures of oppression by murdering her client, but is it an emancipatory act or a brief transitory moment of freedom ? There might not be answers to the question, just as most working women struggle to have answers to this conundrum in today’s capitalist economy. Do their work give women much needed agency or are they facilitators and even proponents of the same vicious economic cycle that they want to break away from?

Jeanne Dielman is considered one of the greatest films ever made. Upon its release, critic Louis Marcorelles called it the ‘first masterpiece of the feminine in the history of the cinema’

Jeanne Dielman is a film which not only illustrates women’s struggles but also contributes to the larger feminist discourse by questioning the politics of representation and spectatorship. The cinematic lens serves as a mirror, allowing us to study, question, and eventually contribute to the ongoing dialogue on gender and its representation in our shared cultural narratives.

References:

Been Watching Films, Y.H. (2023). Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles – the Significance of Banality. [online] www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_oTHWI1JlH8 [Accessed 15 Nov. 2023].

criterioncollection (2015). Chantal Akerman on JEANNE DIELMAN. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8pSNOEYSIlg [Accessed 15 Nov. 2023].

IndieWire (2015). Chantal Akerman’s ‘Jeanne Dielman’ Is a True Action Movie [online] www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_dVc1GsyOZI.

Kinder, M. (1977). Reflections on ‘Jeanne Dielman’. Film Quarterly, 30(4), pp.2–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1211576.

Margulies, I. (1996). Nothing Happens : Chantal Akerman’s Hyperrealist Everyday. Durham ; London: Duke University Press, Cop.

Margulies, I. (2009). A Matter of Time: Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai Du Commerce,1080 Bruxelles. [online] The Criterion Collection. Available at: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1215-a-matter-of-time-jeanne-dielman-23-quai-du-com merce-1080-bruxelles [Accessed 15 Nov. 2023].

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), pp.6–18.

Mulvey, L. (2016). A Neon Sign, a Soup Tureen: the Jeanne Dielman Universe. Film Quarterly, 70(1), pp.25–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2016.70.1.25.

Mulvey, L. (2022). The greatest film of all time: Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. [online] BFI. Available at: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/greatest-film-all-time-jeanne-dielman-23-quaid u-commerce-1080-bruxelles [Accessed 15 Nov. 2023].

Sequeira Brás, P. (2019). Time and Reproductive Labour in Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and Three Sisters (2012). PARSE Journal, (9).

Singh, P. (2021). What Does Feminist Film Theory Say? [online] Feminism in India. Available at https://feminisminindia.com/2021/03/12/what-does-the-feminist-film-theory-say/ [Accessed 11 Nov. 2023].

Strange, V. (2022). What Makes Jeanne Dielman Such a Great Film? [online] www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wj2s3gNs4yI [Accessed 15 Nov. 2023].

The Criterion Collection. (n.d.). Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. [online] Available at: https://www.criterion.com/films/302-jeanne-dielman-23-quai-du-commerce-1080-bruxelles [Accessed 15 Nov. 2023].

Wikipedia. (2021). Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeanne_Dielman.

Winter, J. (2022). The Revelatory Tedium of the New ‘Greatest Film of All Time’. [online] The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-revelatory-tedium-of-the-new-greates t -film-of-all-time [Accessed 18 Nov. 2023].

About the author(s)

Sahil is an India Fellow working with Aajeevika Bureau, where he focuses on promoting labor rights and raising awareness among migrant workers. His work includes conducting sessions on occupational safety, workplace rights, and the importance of collectivization. He also facilitates discussions on issues such as wage stagnation, workplace hazards, and legal redressal mechanisms, empowering workers to advocate for their rights and improve their working conditions.