The first wave of feminist psychoanalysis began with a critiquing of the traditional psychoanalytic theories developed by Sigmund Freud which entails the three comprehensive steps of a framework for understanding human behaviour and mental processes namely id, ego, superego and how these elements often interplay with the human structure of the mind as conscious, subconscious and unconscious that alters according to the situation.

However, Freud’s concept of psychoanalytic concept in his theory was explained in a way that overlooked females saying that they go through an “Electra complex,” the concept that emphasises “anatomic inferiority” that reduced the narratives around women.

The three waves of feminism

Ever since then, the concept of female sexuality has been around, it has been fraught with controversy. This in turn led many women psychoanalysts to examine the matter closely that Feminist Psychoanalysis began as an emerging field of study. Feminist Psychoanalysis has undergone significant evolution since its three waves in the mid-20th century.

It started in the 1960s-1970s when Freud’s emphasis on female passivity, penis envy was challenged. In the second phase, the other female psychoanalysts Jessica Benjamin and Juliet Mitchell presented their argument on the “dilemma of difference” and women’s subjectivity within psychoanalytic frameworks accordingly. The third phase brought attention to intersectionality and women’s identity.

This way, the feminist psychoanalytic theory has been expanding its scope and different scholars are exploring how cultural factors influence the construction of gender identities. It is with the same urgency that the study of females could be understood by female perspectives better, that Simone de Beauvoir and Elaine Showalter, both psychoanalysts re-examine the concept from their perspectives, whose new theories now can provide a reflection and new orientation within existing patriarchal theoretical approaches.

Simone de Beauvoir’s theory

Simone de Beauvoir was a French philosopher, feminist, socialist, social constructivist and writer. Known for her examining traditions around patriarchy that control the physical and economic conditions which always suppress women. The differential beliefs around men and women that stem from the idea of placing women at the centre of marriage and motherhood are such that they govern what women can do.

Beauvoir’s The Second Sex is the work that created a theoretical and a philosophical basis as Damaru writes for materialists. Her book interrogates the whole position of and traditional role of women in society and she also addresses herself to the matter around the representation of women by many male writers such as D.H. Lawrence.

Beauvoir was also the one to examine ways in which men depict women in fiction. Her work was able to establish the principles of modern feminism which according to Jeremy Hawthorn, brought second feminism, which is the historical account of female suffering during the 19th century.

According to Beauvoir, the fundamental issue of modern feminism is that the man defines the human, not the “woman.” By this, women are merely the negative object or “other” to man, who is the collective identity of humanity. For instance, in grammar, we are used to the way of using pronouns such as “he” to both genders. Beauvoir’s idea of The Second Sex opposes the very idea of logocentric and phallocentric phrases.

The other way around for females, according to Beauvoir, is that women are constructed socially. As a result, women are not born but made. Terms like man and woman are products all social, not biological.

The biological constitution of male and female ties to our cultural programming as Tyson said. Opposing the patriarch’s assumptions about women that they should be mothers is something true as not every woman wants to bear a child, and not all women inherit a maternal instinct.

Yet patriarchy is such that it always forces women to embellish motherhood narratives. Women are always compared by what she is not. Beauvoir turns to the study of biology, psychoanalysis and historical materialism to understand how female humans come as subordinates to society.

Beauvoir traces female development that spans through the formative years of women’s childhood, youth and sexual initiation. Women are characterised as womanly when they don’t lose their reproductive capacity or else, they would be losing their primary life purpose, and identity. The very fact that women’s subordinating situation is because of the result of the character but the character that is inflicted by circumstances.

Only in work, can she attain economic independence. Presenting women as the “other” Beauvoir explores the historical oppression. Beauvoir observes men as essential subjects while women as dependent beings. The way word “other” implies otherness, in the same way, it implies women. She is a man’s “other.”

For instance, the use of certain terms creates a duality effect such as Masculine/Feminine, son/daughter, father/mother, reason/emotion etc which shows that the first term is always going to be superior to the latter. Women are not just controlled by men. However, women of the higher class cannot associate themselves with the women of the lowered class. Women are tied to men because of biological factors but in actuality, the truth is men are dependent on women.

Beauvoir is anti-traditional in a way she explains about the second sex however she resorts to saying that if you take away the male sex, the females would be complemented rather than stripped, riding the two wheels of the cart together. The only aim of her was not to emphasise the women’s position as inferior but to return to the state of equity.

Elaine Showalter in Toward a Feminist Poetics

Elaine Showalter is an American literary feminist and writer on social issues. One of the founders of feminist theory developed the concept of gynocritics. Like Beauvoir, Showalter examines the struggle of females for identity and gynocritics, the study of females not just as a gender but as internalised consciousness of the female. Often feminism is critiqued because it sees female critics with a phallocentric perspective. Wondering if that is something that lacks the theory, Showalter’s response is Toward a Feminist Poetics.

Two of the varieties were divided; women as readers as “Feminist Critique,” and women as writers as “Gynocritics.” According to this theory of feminist critique, “when a woman studies the work of male writers, she presents the belief that was mentioned about her in the text.”

The stereotypes subject included in this is present in literature about women where it analyses the historical treatment of the male writers illustrated to the female characters. It means females here can understand women based on their imagination and understanding of them by men and men cannot perfectly sketch the female character the way female writers do.

The main issue associated with this critique is that it is male–oriented. Furthermore, Dilip writes, “If we study stereotypes of women, the sexism of male critics, and the limited roles women play in literary history, we are not learning what women have felt and experienced, but only what men thought women should be. […] The critique also has a tendency to naturalize women’s victimization by making it the inevitable and obsessive topic of discussion.” It meant the issue of women understanding women is real.

In terms of gynocritics as a writer, Showalter emphasises that in order to understand the literature created by women, the framework has to be constructed by females. It doesn’t mean to erase the male writing at the expense of uplifting women. But that “Gynocritics begins at the point when we free ourselves from the linear absolutes of male literary history, stop trying to fit women between the lines of the male tradition, and focus instead on the newly visible world of female culture.” For this, the study will be based on the psychodynamics of female creativity, with the intent to create a literary critique of female experiences.

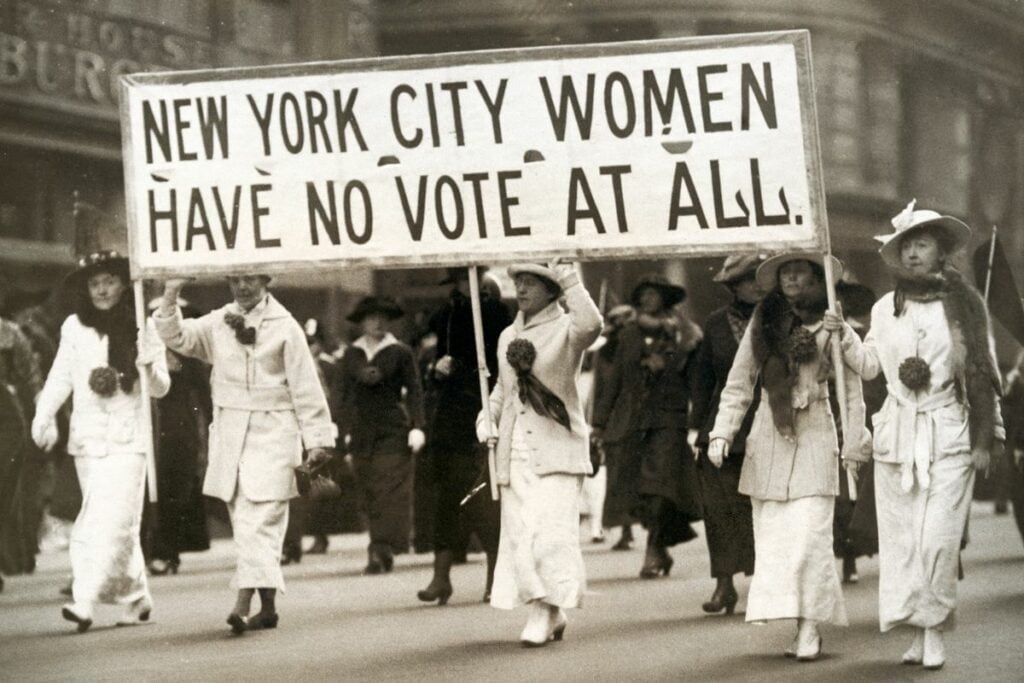

Showalter’s feminist theory spans about three phases sketching the history of women writers. The first phase (1840-1880) was the period when women writers wrote at the same magnitude as men but they used male pseudonyms which was the “Feminine” phase. The second phase was the “Feminist phase” (1882-1920) where women expressed their sufferings and they got voting rights. While the third phase the “female” phase is the self-inventing one. Women in this phase started to reject imitation and domination.

A lot of women writers like Virginia Woolf and Elizabeth Barret Browning should be read politically, and socially in the context of gynocriticism. Virginia Woolf in her essay ‘Women and Fiction,’ (1929) writes, “In dealing with women as writers, as much elasticity as possible is desirable; it is necessary to leave oneself room to deal with other things besides their work, so much has that work been influenced by conditions that have nothing whatever to do with art.”

An example that showcases this is also Barrett’s, ‘Aurora Leigh,’ where Cora Kaplan discusses the writer’s milieu that defines her feminism as bourgeois. However, she forgets one of the male writers that impacted her. It’s always a problem for a woman writer to marry a man because that doesn’t comply with societal norms. Evident in George Eliot’s work, most of the female characters do not become what they wish and they die.

Beauvoir, Showalter and the lessons learnt

In a nutshell, if Beauvoir argues for the liberation of women out of social constraints, Showalter on the other hand, emphasises that women’s literature should rise out of death, suffering and compromises. For Beauvoir, women’s equality comes as they break out from the patriarchal chain, whose opinion around women as a second sex isn’t that much of a thing. But Showalter’s critique couldn’t be easily made possible because to study and build the critique through women’s history, they must have written something about it.

If Beauvoir interrogates what women are and should be, Showalter is there to assert and hold the women slipping out of literature. For both of them, Showalter and Beauvoir are known as the few women standing strongest against all the odds, and asserting not just their identity and sense of self but for many women, whose narrative otherwise wouldn’t have come out in academia today.

About the author(s)

Susmita Aryal is a final year student of English Literature and Journalism at St. Xavier's College, Maitighar, Kathmandu. Besides storytelling around identity, gender and society, she is interested in 'art' i.e. any kind of artworks that fall under the genre of art.