‘The quality of a good leader is that they show up when times are tough,’ Leni Robredo declared standing alone in a presidential election debate in 2022 on CNN Philippines, where her rival Ferdinand Marcos Jr—the son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos—remained absent.

For standing up to the dangerous elements of today’s political reality—racial and socio-economic disparities and crackdowns on dissent, among them—both Robredo in the Philippines and Márquez in Colombia faced threats online and offline.

The same year, in Colombia, Francia Márquez showed up in tough times. Running for president in a political terrain hardly conducive for a black candidate, let alone a rural single mother, she reduced hundreds to tears with her speech: ‘We’re not descendants of slaves. We’re descendants of free men and women who were enslaved.’

The two women have been strong voices of reason advocating against authoritarian environments in their respective democracies, as two documentaries—belonging to separate parts of the world but bearing themes that rhyme—showed at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah recently.

Here, And So It Begins, directed by Ramona Diaz, depicted the struggle of Robredo who was elected Vice President from an opposing ticket between 2016 and 2022 and endured sexist jibes about the length of her dresses from president Rodrigo Duterte who went on to call her term ‘a colossal blunder’. Likewise, Juan Mejía Botero’s Igualada documented how Márquez turned ‘Igualada’ a slur aimed at people asking for rights and privileges that supposedly don’t correspond to them, into a clarion call to energise support for her campaign for democracy.

For standing up to the dangerous elements of today’s political reality—racial and socio-economic disparities and crackdowns on dissent, among them—both Robredo in the Philippines and Márquez in Colombia faced threats online and offline. It also earned them a following that swelled from modest to impressive numbers. Where the documentaries excel is in parachuting viewers into the colourful movements that grew around these leaders.

The cost and colour of elections in And So It Begins and Igualada

Robredo’s fans know how to throw a party, bringing strings of homemade pink flags and custom-stitched drag costumes to the rallies and performing cover songs such as ‘Leni Be’ to the tune of The Beatles’ ‘Let It Be’. On her final night of campaigning — complete with song, dance and speech — we see a pink-clad crowd go from a few thousands to more than 700,000 people.

In Igualada, we glimpse the subalterns, in Colombian terms ‘los nadies’ (the nobodies), who stand with the left-wing candidate Márquez and grow in strength poll after poll. To them, ‘Francia is Colombia’.

Márquez, we learn from the film, got her start in grassroots activism as a young woman growing up in the mining community in La Toma.

Márquez, we learn from the film, got her start in grassroots activism as a young woman growing up in the mining community in La Toma. In that milieu, from the 1990s, right wing paramilitary forces had intensified the ongoing civil war in Colombia, and begun evicting traditional miners from their home so that vested entities could usurp the gold deposits abundant there.

The cost of challenging the status quo as a presidential hopeful becomes clear in a particularly affecting moment in Igualada, where abruptly during her speech, bodyguards have to shuffle to cover Marquez with bulletproof shields over rampant fears of assassination.

In the Philippines, after Robredo made a bid to be head of state, the online attacks were so relentless she had to set up a team of specialists who bust fake news ‘within four hours’ or else ‘people believe it’. She enjoys the endorsement of Nobel-winning journalist Maria Ressa, co-founder of Rappler and a fierce Duterte critic. Ressa was also at the centre of director Diaz’s previous work, A Thousand Cuts (2020), to which this film is a companion piece.

What makes And So It Begins and Igualada stand out is the extensive access the filmmakers enjoyed to their subjects. For instance, Diaz is in the room as Robredo gets her makeup done, when the distress of trolling has her posing for fewer photographs, and she interacts with followers for months on the road.

As for the Colombian documentarian, Botero’s effort spans 15 years. He had befriended Márquez in the late 2000s, filming as she enlisted people to the resistance in La Toma, and started this film when she decided to run for presidency in 2020.

Winning vs worthiness in And So It Begins and Igualada

To be clear, the films are not trying to be anything other than hagiographies. This candidate is worthy, is each documentarian’s direct message.

To be clear, the films are not trying to be anything other than hagiographies. This candidate is worthy, is each documentarian’s direct message.

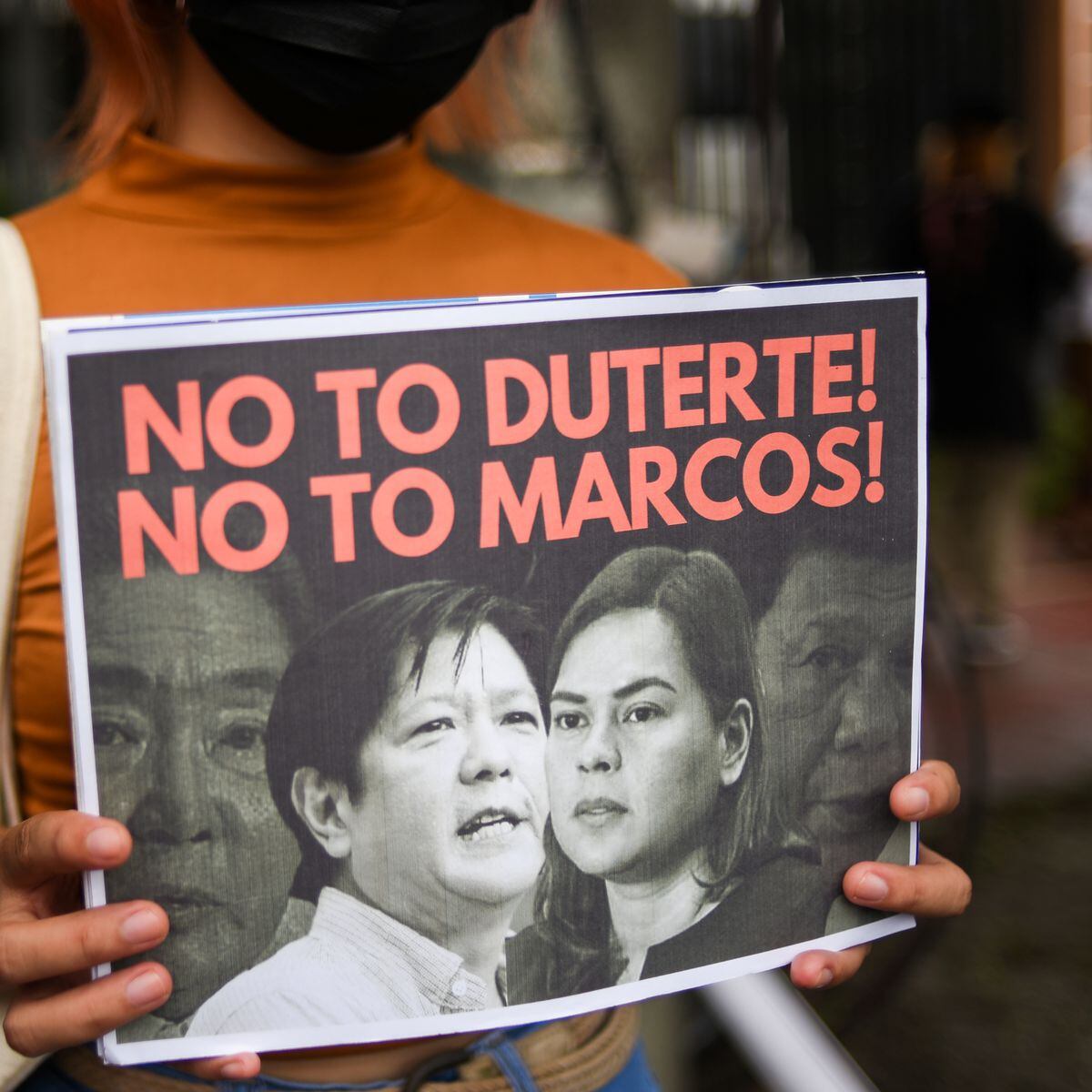

In fact, anyone coming to And So It Begins with no context for Leni Robredo may walk away without learning enough. While the film tells us she is the wife of politician Jesse M Robredo, who died in a plane crash in 2012, it does not dive deep into what caused her entry in politics or what her specific goals are. She is the non-dictatorial alternative to Marcos, goes the broad gist. It does paint a picture of what she is up against — the green-and-red rallies the rival camp is holding, and the project of historical revisionism underway to glorify the Marcos name.

Botero’s Igualada remains embedded in Márquez’s experiences, following her work and life with empathy. But it does venture beyond politics to offer a picture of her ties with her ancestral land, her beginnings as an articulate teen activist, and her struggle as a single mother in public affairs whose family is subject to threats too.

A spoiler alert for those not in the know: neither Robredo nor Márquez became president. While the former lost by a large margin, the latter did have reason to celebrate — she was offered a nomination that eventually got her elected as the country’s first black vice president.

That their story need not end with their losses was the sunny outlook of the films screened at Sundance.

That their story need not end with their losses was the sunny outlook of the films screened at Sundance. What the audience took away was how hope and joy can persist even in an ailing democracy and become catalysts of resistance and resilience.

Still at work

The presidential hopefuls on separate sides of the world owned her gender.

The former vice president of the Philippines, only the second woman in the country to have held that position, did not allow prejudice to disturb her pleasant demeanour. Diaz’s portrait of Robredo presents her always smiling, even as Duterte insinuates she lacked the fire to be president. Robredo’s counter, in a notable speech during her presidency bid: ‘I am a mother who will always look after her children.’

Like Robredo, Márquez met and cast aside attacks, which in her case, were not just sexist but also racist. ‘Political participation for women like me isn’t easy, especially when we are willing to disrupt the status quo. But defying fear is part of achieving justice and it is what I have been doing all my life.’

At the premiere of the Colombian film at Sundance, a member of Márquez’s movement noted that the vice presidency has so far allowed only a partial version of the leader’s vision. ‘She’s determined to change what is going on for 300 or more years. We believe it will be possible to succeed,’ the volunteer noted. The Philippines’ Robredo, as she had done on the day after the election loss, got on stage at the premiere of Diaz’s documentary. There, she assured a group of admiring Filipinos in the American audience that her campaign ‘is not over. It will go on’.

For both leaders, it continues to be about ‘showing up’