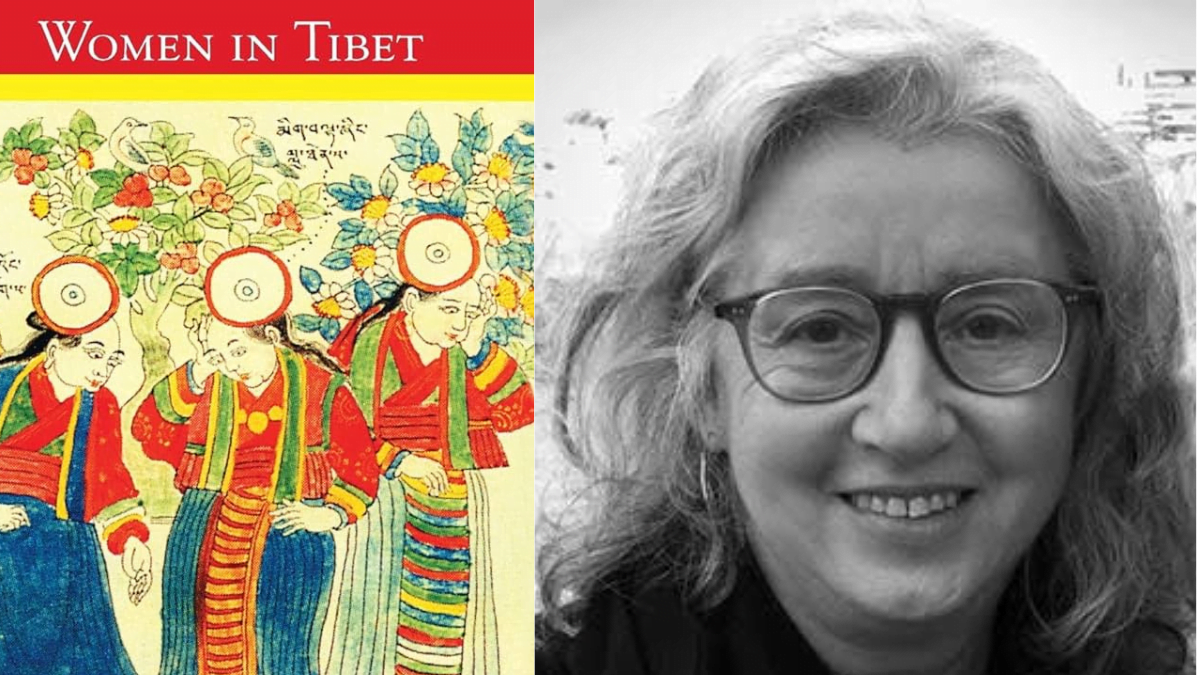

Women in Tibet: Past and Present, edited by Janet Gyatso and Hanna Havnevik, offers a thorough examination of Tibetan women’s lives, covering their history, challenges, and achievements. This anthology sheds light on often overlooked narratives, emphasising women’s resilience, agency, and societal contributions. It explores the complexities of Tibetan women’s experiences over time, revealing evolving socio-cultural dynamics and their impact on women’s roles and aspirations.

This anthology sheds light on often overlooked narratives, emphasising women’s resilience, agency, and societal contributions.

Beginning with an exploration of women’s roles in the traditional society of Tibet, the anthology draws from historical sources such as ancient texts and inscriptions from the Tibetan empire era. Authors in this section analyse gender relations, family structures, and religious practices, providing nuanced insights into historical experiences.

In the latter part of the book, attention turns to contemporary challenges faced by women in Tibet, examined through ethnographic research and field interviews. This section explores how modern political changes, migration, and globalisation have affected Tibetan women. It highlights their struggles to preserve cultural heritage amidst rapid change, with personal narratives illustrating resilience and determination. These stories emphasise women’s empowerment, pursuit of education, and activism, showcasing their ability to enact positive change in their communities.

Throughout the chapters, a consistent theme revolves around the methodological challenges associated with studying ‘Tibetan women‘. The authors discuss the inherent selectivity in reporting, the various historical perspectives on women’s status within Tibetan society, and the recurring instances of deviations from established norms. It’s noted that the category of women doesn’t align precisely with the fluid gender norms that exist, and caution is repeatedly emphasised regarding the perils of overgeneralisation. These perils are not solely due to indigenous and physical disparities but also because of the evolving conceptions of womanhood and personhood, regardless of gender, throughout Tibetan history.

As the analysis progresses, the focus expands to include recurring motifs such as religion and spirituality, with a particular emphasis on the portrayal of women’s bodies across multiple chapters.

As the analysis progresses, the focus expands to include recurring motifs such as religion and spirituality, with a particular emphasis on the portrayal of women’s bodies across multiple chapters. The evolution of the function and significance attributed to women’s bodies is observed, transitioning from primarily serving as conduits for family lineage perpetuation in ancient Tibetan society to becoming significant centers of political expression in contemporary Tibetan culture. This transformation is closely intertwined with another theme present in the anthology: the women’s endeavor to reclaim their Tibetan identity and culture while asserting their voices amidst political challenges

The body of the Tibetan woman as a site of reproduction

The Genealogy of the imperial household offers a fascinating glimpse into the intricate dynamics of women’s roles in historical Tibet. It predominantly lists consorts who bore heirs, prompting speculation about whether a consort’s fame was solely tied to her ability to produce male heirs for the throne (p.46). This raises questions about the overlooked consorts who played vital roles in the imperial court regardless of childbirth. Empresses, even if they bore heirs, were seldom mentioned in historical records, indicating their relative visibility compared to other consorts and wives, whose recognition often came posthumously. Additionally, sisters and daughters of emperors were mentioned only upon marriage, suggesting their significance depended on being entrusted to another man’s care, often unrelated.

In a similar breath of thought, the Annals too shed light on the differentiation in forms of address amongst the various female members of the imperial household on the basis of their utility , with mothers to heirs of the throne being honored as ‘yum’ (mother) or ‘chi’ (grandmother) or sometimes even the high-ranking title of ‘mangmoje’ signifying their role as the sovereign lady of many. Furthermore, the hierarchical structure of the imperial household, with titles like ‘empress’ applied to various women, including the principal consort and imperial princesses, underscores the complexity of women’s roles and ranks. This intricate web of titles and roles reflects the intricate nature of women’s positions within the imperial court, each title representing a different facet of their significance in the historical narrative

The body of the Tibetan woman as a symbol of disruption

In Tibetan society, traditional gender roles require young men to pursue monastic life, while young women are expected to enter patrilocal marriages (p.263). These roles are rooted in the belief that women possess limited mental capacities compared to men, implying their perceived inferiority in emotional regulation, bodily control, and focused thinking (ibid). This division reinforces women as foundational support for male endeavors and forms spatial distinctions, placing the female body in the profane realm and the male mind in the sacred sphere.

However, young women, especially from economically disadvantaged areas, started showing interest in nunhood to escape household burdens and labor (p.277). This trend grew where arranged marriages and women’s heavy farm work became societal norms (ibid). Voluntary celibacy and opting out of motherhood provided autonomy for vulnerable women facing state birth control measures.

As Charlene Mackley argues, nuns challenge established gender norms in Tibetan society, especially with the state enforcing childbirth quotas and the encroachment of Han and Muslim Chinese settlements, diminishing male authority (p.283). The androgynous appearance of young nuns highlights the contrast between marriage and procreation in a society where both are scarce. Despite leading celibate lives, nuns often faced scandalous gossip, silently enduring societal representations of their ritually marked bodies (p.284). Their rejection of traditional gender roles made them central in opposing evolving gender practices, seen as perplexing and multifaceted (ibid). This gossip attributed to nuns a significant, unintentional influence in disrupting the gender binary foundation of Tibetan social structures. Consequently, nuns’ bodies symbolise a society in transition, caught between tradition and transformation

The body of the Tibetan woman as a site of political resistance

In the struggle against the Chinese state, Tibetan women have found their bodies to be powerful tools of political defiance, transcending individual incidents like forced abortion and sterilisation to embody deeply personal resistance (p.362). Negative experiences, such as betrayal or witnessing abuse, often manifest physically or mentally, highlighting the strong link between psychological and somatic well-being across different backgrounds, including urban and rural women, educated and uneducated, and various historical periods.

In Lhasa’s prisons, women’s bodies become focal points of conflict and resistance, particularly evident in the accounts of incarcerated nuns who endured imprisonment from a young age (p.334). As public spaces shrink, women’s bodies become contested terrain, symbolising cultural identity and group cohesion through concise, emotionally charged rituals reflecting Tibetan values.

As public spaces shrink, women’s bodies become contested terrain, symbolising cultural identity and group cohesion through concise, emotionally charged rituals reflecting Tibetan values.

Tibetan nuns have significantly reshaped protest into a non-violent act, intertwining it with ritual, religion, and femininity (p.333). Through methods like singing, hunger strikes, and prayers in prison, they demonstrated that these actions are deeply internalised and aligned with Tibetan Buddhist principles. Their non-violent strategies effectively portrayed the state as an oppressive force to the international community, challenging the state’s narrative of authority and masculinity (p.337). These acts of resistance affirmed cultural identity and countered physical manifestations of political oppression.

Beyond nuns, the state also utilises the female form to assert control, as seen in the case of correctional officials at Drapchi prison who banned nuns from cutting their hair, turning the body into a stage for political displays once again

The shortcomings of the book

While commendable, the book on Tibetan women lacks depth in certain areas. It could have provided a more thorough analysis of the historical and cultural factors influencing Tibetan women’s status, offering deeper insights into socio-political dynamics and traditional customs. Additionally, while addressing challenges faced by Tibetan women, it could have explored key issues like education, healthcare, and employment opportunities in greater detail to provide a nuanced understanding of their struggles.

Moreover, the book primarily focuses on Tibetan women’s narratives within Tibetan society, overlooking their interactions and contributions on a broader scale. Exploring their engagement with the international community, experiences of Tibetan women in exile, and involvement in global feminist movements would have offered a more holistic perspective.

Lastly, while touching upon external forces like the Chinese occupation and modernisation, the book lacks a critical analysis of their impact on Tibetan women’s lives. A deeper examination of the complexities and specific challenges faced by Tibetan women in the contemporary political climate would have enriched the discussion.

Before this book’s publication, scholarship on Tibetan women largely focused on autobiographies of prominent figures like Ama Adhe (The Voice that Remembers: A Tibetan Woman’s Inspiring Story of Survival) or narratives of nuns and female mystics in Tibetan Buddhism (Women of Wisdom, Lady of the Lotus-Born: The Life and Enlightenment of Yeshe Tsogyal). These accounts overlooked the experiences of ordinary Tibetan women, creating a gap in understanding. Women in Tibet: Past and Present fills this void by presenting diverse stories of Tibetan women from various backgrounds and time periods.

This collection not only contributes to academic discourse but also engages policymakers, activists, and the general public in discussions about gender in Tibetan society. It encourages further research and advocacy for Tibetan women’s rights on a global scale. Additionally, it has empowered formerly incarcerated Tibetan women to step forward and share their firsthand narratives of experiences as prisoners, as seen in recent publications like Tibet in Chains: The Stories of Nine Tibetan Nuns. In conclusion, Women in Tibet: Past and Present is a significant milestone in Tibetan women’s studies, highlighting their struggles and accomplishments while promoting inclusivity and equity for the future.