Picking a fuschia pink blouse, a white blazer and beige pants to go with it, I stand in front of the mirror in my apartment, brushing my hair until each strand is perfectly untangled. Rummaging through my makeup pouch, I settle on the brightest shade of pink for my lips, and putting on my stilettos, head off to a brunch party. At the venue, someone compliments my shirt, while a friend asks me about my earrings: she wants me to give her some fashion tips.

As I move towards the bar to get me a drink, I hear a person jokingly tease their friend, saying, “What on Earth are you wearing, you look no less than a chamar!” I let out a heavy sigh. While moments ago the same individual had nodded in my direction admiringly, in a hot second they had berated my community and my Dalit identity. It was just one word, but it was a slur that spoke volumes.

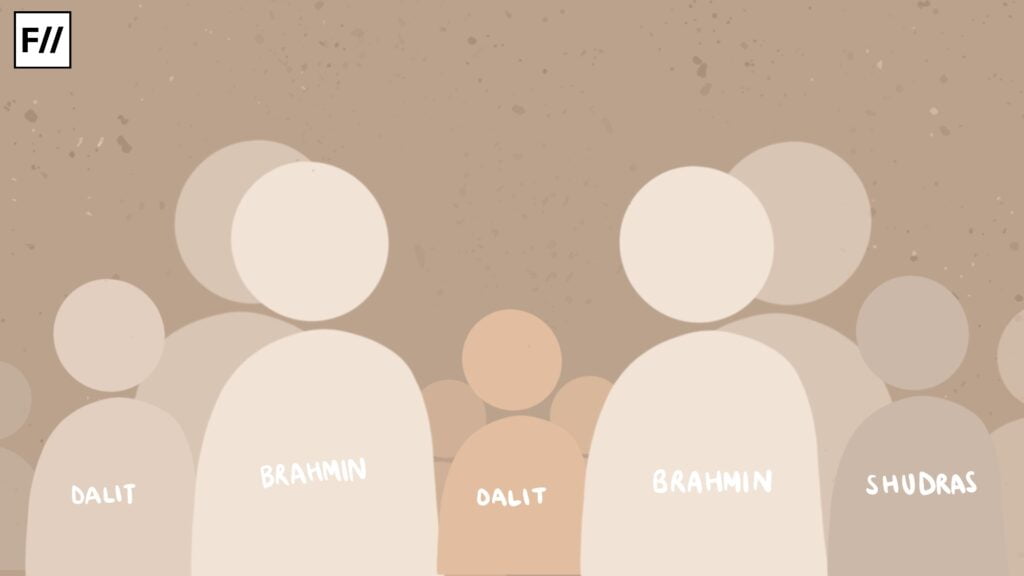

It openly declared that caste is directly proportional to the way one looks. The lower the caste, the greater the insult. Because like all opportunities, being well-dressed is also reserved with being a savarna.

It openly declared that caste is directly proportional to the way one looks. The lower the caste, the greater the insult. Because like all opportunities, being well-dressed is also reserved with being a savarna.

During college, I had a paper on Dr B.R. Ambedkar in my honours course, which gave me a deeper understanding of the caste system and its far-reaching implications that have resonated until today. Being a Dalit raised in the city, I could see how rooted this evil is in society and the way everything functions, even in the smallest of acts.

Ambedkar famously said, “Educate. Agitate. Organise.” – the three words that urged the Dalit community to rise against the oppression they had faced for centuries. But only a few people know that before these principles, he wanted his people to gain confidence by starting to see themselves and the savarnas as equals. This assertiveness, he said, would come only when the community disregarded the age-old discrimination that became conventions, like eating the meat of dead cattle and maintaining hygiene, which began as a restriction imposed by the Brahmins.

As the father of the Constitution was always seen in a crisp blue suit, white shirt and a red tie, which was a power move showcasing resistance, he pushed Dalits to subvert the “untouchable” tag, just as he did, through cleansing themselves inside out – by having the so-called savarna vegetarian food and putting on a clean attire. Defying the subjugating Manusmriti, the Hindu dharmashastra that blatantly denies the shudras every right to being human, the avarnas, henceforth, followed in the footsteps of Babasaheb, laying the groundwork for the future generations.

But it led me to think: how much has changed?

While many Dalit families like mine progressed and moved towards urban life, the stereotypes associated with the scheduled classes stayed put at the far end of the timeline. Even today, we are faced with questions like, “You don’t look that way,” as if being presentable unsettles the appearance politics as we see in films, where a lower caste individual is portrayed as the Brahmanical society wants to see: dark-skinned, shabby, soiled and covered in grime, living in dire economic conditions.

Moreover, instead of casting Dalits for the said role, filmmakers choose savarna actors for the portrayal, darkening their faces to “fit” the part. This caters to the upper caste gaze which identifies the existence of marginalised communities with victimhood, where a savarna individual would be responsible for “saving” the oppressed ones, much like a Nietzschean übermensch. Take pop culture examples like Ketan Mehta’s Manjhi: The Mountain Man, Anubhav Sinha’s Article 15 and Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan.

Every morning, as I stand in front of my wardrobe, sifting through the hangers of tops and trousers, I can’t stop thinking about how living as a woman belonging to the Dalit community is scary, as being doubly oppressed means you’re not safe at any time. Think of the oppression that came in the form of the ‘breast tax‘ in Kerala.

Just three hundred years ago, women of the backward classes were supposed to pay taxes if they wanted to cover their breasts, a time when modesty and respect were also a luxury. It is said that a young Ezhava woman from Cherthala in Alappuzha, tired of the daily humiliation, cut off her breasts instead of paying money to the tax officials as an act of defiance against the casteist royals. While she bled to death, her kith and her kin were forced to leave the area as the savarnas couldn’t bear to live with the truth that a woman from the lower caste had challenged the authorities.

Sadly, this injustice isn’t a thing of the past centuries. Cases of violence have been registered where men and women have been lynched, chastised and murdered for merely dressing with dignity. In 2023, a Dalit man in Gujarat was thrashed for dressing well and wearing sunglasses. Reason? He was “flying too high,” a very valid statement recorded by the savarna group.

Another young man in Rajasthan was killed for the criminal mistake of sporting a moustache, which is generally associated with the upper caste Kshatriya clan. Moreover, a Dalit wedding ceremony was disrupted, because the gold jewellery of the bride and the pleasant arrangements didn’t sit well with the Brahmanical people of the village. The common thread in all these cases and more is that the fragile ego of upper-caste individuals couldn’t bear the well-dressed avarnas challenging the caste status quo.

Why is there discomfort in the minds of savarnas when they find that people from the ‘lowewerd castes‘ are making sartorial choices similar to theirs? Why are they feeling threatened?

Granted, fashion choices and dressing up are synonymous with privilege and reflective of the financial abilities of a person. However, when it comes to pigeonholing an entire caste as looking a certain way, hard thought is required towards the discourse – how is it fair to stereotype the Dalit community as a product of glaring casteism? Why is there discomfort in the minds of savarnas when they find that people from the ‘lowewerd castes‘ are making sartorial choices similar to theirs? Why are they feeling threatened?

Until these difficult questions are acknowledged, I think I’ve found myself a temporary answer. If dressing up well is a way to destabilise the caste system, then so be it. Hence, I’ll be donning a bandhej kurta and wearing a black bindi, waiting for someone to come up to me and strike up a conversation. But I’ll be ready when they say, “You don’t look Dalit.” Because I know they will.