Of late, it has been established that stardom of the yester-years does not inform the contours of stardom in the age of social media, where privacy and mystery have been rendered antiquated. As famous actors along with those struggling reveal their personas on the internet and routinely empty any residual sense of enigma in their pursuit of creating a brand of themselves, the traditionally manufactured distance between the spectator and the star-actor has collapsed. For Karan Johar, actors nowadays can only claim for themselves the tag of popularity but not that of a star.

As famous actors along with those struggling reveal their personas on the internet and routinely empty any residual sense of enigma in their pursuit of creating a brand of themselves, the traditionally manufactured distance between the spectator and the star-actor has collapsed.

He is right in observing that the constituents of stardom, “the magnetism, the mystique, and the aura” are missing. So, how does one reconfigure stardom in the age of social media? More particularly, how does Dharma Productions (among many other production houses of the Hindi film industry) attempt to repackage it in an age when stardom appears as a forgotten and banished deity?

The star-kid enters the frame

For this article, Dharma simply works as a synecdoche to think about the contemporary culture of stardom, and the author’s attempt should not be misconstrued as one that wilfully isolates and vilifies a particular production house. It is simply to understand one of the new ways in which the star-kid is accommodated in the film-industry. Earlier, allegations against kinship-structure-driven casting decisions did not lead to as much uproar as in the last few years which has impacted the entry of Janhvi Kapoor, Ishaan Khattar, Sara Ali Khan, Ananya Pandey, Suhana Khan, Agastya Nanda, Babil Khan, Khushi Kapoor, among others.

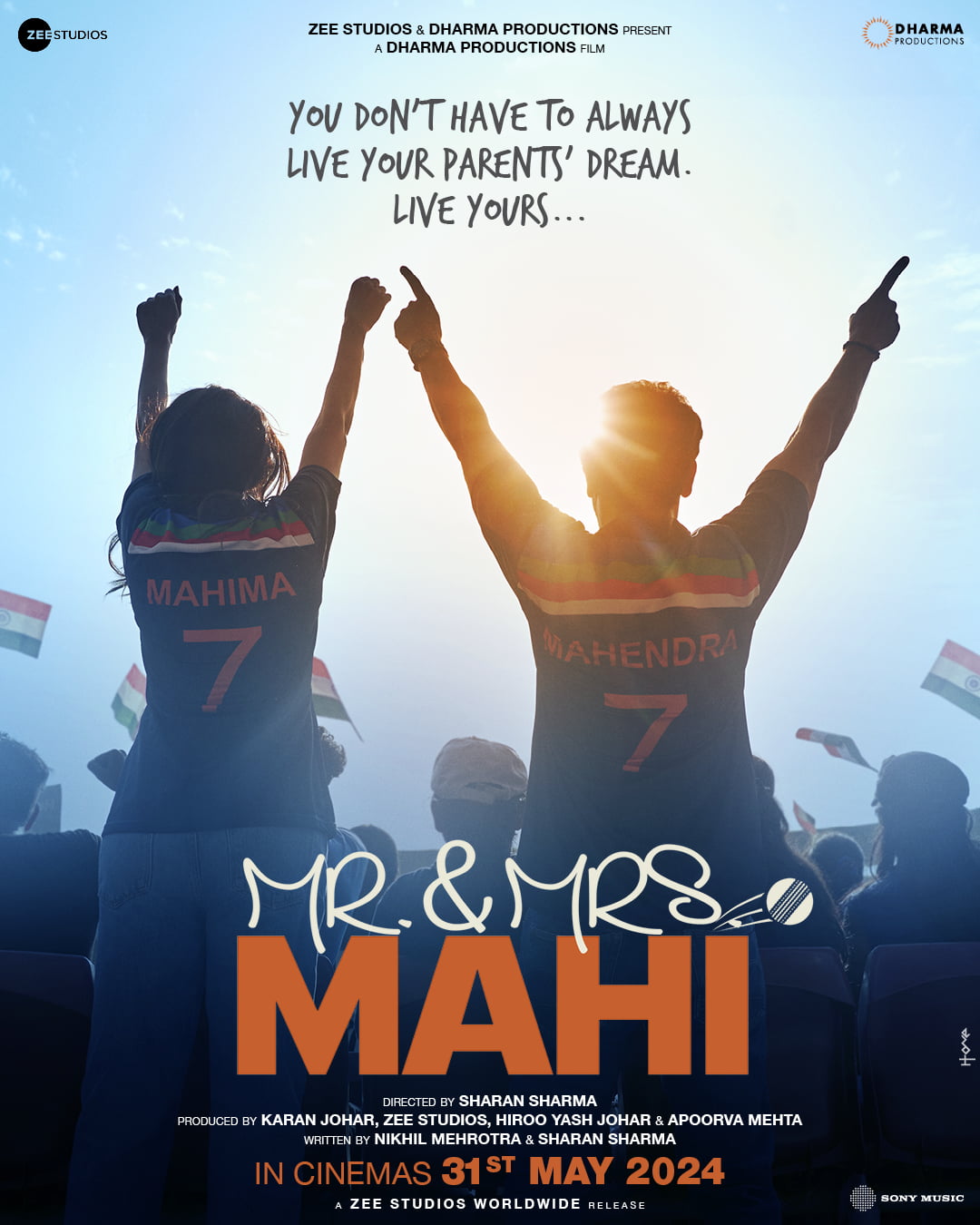

While writing the previous line, one suspects that young women have been disproportionately castigated in comparison to their male counterparts. One also recognises that the daughters of superstars (and others having connections within the film family) have entered the industry before their sons, and one might need to wait a little before the bigger picture emerges. In any case, it cannot be denied that patriarchal regulation of thought devises several modes to impede the entry of girls and women into public life. By looking at Sharan Sharma’s Mr. and Mrs. Mahi, one can unpack the conflicting ways in which the star-system persists in the present.

Tranquilising the politics of gender in Mr. and Mrs. Mahi

The filmic narrative of Mr. and Mrs. Mahi belongs to the same template as that of films like Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Abhimaan, which in turn was based on the Bengali film Bilambita Loy. In other words, one can argue that the film’s outline is driven by a formula. A talented-unsuccessful-insecure man paired with a talented-successful-forgiving woman. However, the fascinating change is that gender quickly, if not from the beginning, becomes a smokescreen.

First, the differences between the husband, Mahendra (Rajkumar Rao) and the wife, Mahima (Janhvi Kapoor) are blurred by providing them with uncannily synchronous childhood stories which are further represented as visual corollaries. She accepts a life of academia (becomes a doctor) as proposed by her father, whereas he tries till he is an adult to succeed as a cricketer in rebellion with his father.

The filmic narrative of Mr. and Mrs. Mahi belongs to the same template as that of films like Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Abhimaan, which in turn was based on the Bengali film Bilambita Loy.

Mr. and Mrs. Mahi does not seem to suggest it is gender that restricts choice or opportunity but a matter of individual character; she merely acquiesces with parental upbringing as he attempts to defy it. In both cases, it is the orthodoxy of parents that determines the fate of their children, regardless of their gender.

Second, no visible signs of gender inequality (via the reaction of family members) invade Mr. and Mrs. Mahi, which is otherwise unabashedly popular and does not shy away from the formulaic. It would not have been surprising to witness somebody express an incongruity at the sight of a girl playing sport/cricket.

But, Mr. and Mrs. Mahi portrays for us a world which has resolved manufactured paradoxes like these, it seems to convince the spectator that it is not because Mahima is a girl that the father (Purnendu Bhattacharya) pushes her to become a doctor instead it his middle-class beliefs which concede to the uncertainties of a career in sports. Similarly, the in-law family has no objections to the daughter-in-law’s sudden change in career plans. The father-in-law (Kumud Mishra), who was adamant to regulate his son’s aspirations, ostensibly has no authority in the decision-making process of Mahima’s entry into cricket.

Not only the daughter, but the daughter-in-law too seems liberated from the weight of patriarchal institutions. The world has changed, Mr. and Mrs. Mahi proclaims. In Kapoor’s previous outing with Sharma’s Gunjan Saxena: The Kargil Girl, subversion of gender power relations successfully drove the film forward, albeit with the use of clichés. In these films, Kapoor’s demure physiognomy was not relegated to a mere character trait, rather her femininity added a certain flexibility to the moulds of the body as it confronted and moved inside typically masculine worlds.

Therefore, one wonders what does Sharan Sharma accomplish by suspending gender power relations in Mr. and Mrs. Mahi? There are but two moments where gender becomes apparent. Mahendra in anger throws the ball so fast and without any gap in between one and the other that it hits Mahima’s helmet and impacts her head. Serving as a visual cue for the conflict to follow, the violence becomes reminiscent of masculine aggression and carelessness. Another is when the mother (Zarina Wahab) sits with an upset Mahendra and by the end of the scene makes her position as the sole-provider of care visible to him.

Gender, in its political sense, largely remains absent from the film’s text and texture.

Gender, in its political sense, largely remains absent from the film’s text and texture. Yet, it is interesting to note that though gender is made irrelevant in making it a story of two kids whose dreams are restricted by parental suppression or chastisement, it is simultaneously made relevant (or rather made use of) to contribute to the ecosystem of Janhvi Kapoor’s stardom.

Mr. and Mrs. Mahi: Masking stardom on the ground of cricket

By using yet another smokescreen, this time of cricket, Mr. and Mrs. Mahi’s subtext is heavily invested in the question of cinematic stardom and fame. Resorting to the cultural footprint of Shah-Rukh and Kajol’s star personas by rehashing the song “Dekhha Tennu” as an instrument of the film’s promotion supplies us with a tailor-made lens to perceive this subtext.

Quickly into Mr. and Mrs. Mahi, Mahendra’s brother is introduced walking out of the airport with a swarm of paparazzi taking his photographs. As a celebrity, he is shown to be shallow and driven by a need to corporatise his self, a reality with which he familiarises Mahendra later in the film. Through this brief encounter, one presumes he is a run-of-the-mill influencer, sunk into the rabbit hole of marketing his self by hook or crook. Fame and stardom, one is told, comes cheap in the new millennium. But Mr. and Mrs. Mahi also insists on carving a niche space for Kapoor within this very world.

And here lies its main impact by creating a dyad between Rao – the outsider, the actor, and Kapoor – the famed star kid. In his perpetual inability to grasp the mantle of fame, Rao’s character challenges, on more than one occasion, her newly gained status as a star. Meanwhile, Kapoor’s character’s talent goes unquestioned, and this is perhaps the film’s biggest shortcoming. For the spectator, she is talented without a shred of doubt, despite her attempts to efface that self by accessing her identity through Mahendra. Luck that has been seldom bestowed on Mahendra teams up with her narratively and subsumes it naturally under her talent.

Nevertheless, one gets the sense that Mr. and Mrs. Mahi is not simply a conflict between the husband and the wife, the man and the woman, but an actor and a star kid who chooses to be an actor.

Nevertheless, one gets the sense that Mr. and Mrs. Mahi is not simply a conflict between the husband and the wife, the man and the woman, but an actor and a star kid who chooses to be an actor. Like Abhimaan which some believe to be based “on the troublesome marriage between two Hindustani classical music maestros, the sitarist Ravi Sankar and the surbahar player Annapurna Devi,” and others suggest Mukherjee based it on the life of singer Kishore Kumar and his first wife singer-actress Ruma Guha Thakurta, Mr. and Mrs. Mahi structurally addresses the tension between two artists.

In earlier such films, gender was a deeply entrenched system of regulation and it still is. But here, the complication is that gender power relations remain suspended unless they are in service of creating an extra-cinematic landscape unblemished by the charges of nepotism for Kapoor. All the anger that Rao’s Mahendra harbours seems to be conceived, at first glance, as masculine, when it can be, and there is enough evidence for that in Mr. and Mrs. Mahi, stipulated as the rage of actors who are not privy to the large networks of associations within the film industry.

In one sense then, Mr. and Mrs. Mahi comes across as a wicked project to brush away the taints of nepotism and the way kinship structures control and organise the Hindi film industry. In its alignment with the politics of Dharma, where nepotism/feudalism is rarely ever publicly discarded or seen as a drawback – something that of late Zoya Akhtar (in her response to The Archies) has also been complicit in – the film’s content gets shaped by the politics of the industry relations.

The possibility of an alternative reading of Mr. and Mrs. Mahi

If the arguments above are reasonable, then one begins to suspect the larger ideological footprint of Mr. and Mrs. Mahi. But the climax fascinatingly complicates this reading; it reserves the purity of art, the multi-dimensional nature of acting, the grasp on greyness and ethical fluidity, and an introspective character arc squarely with Rajkumar Rao. As he is shown content with his hand on his heart, disinterested in the media outside his house, the spectator is led to believe that the star-machinery, which serves those who have easily gotten opportunities, is more fragile than ever – shattered by even the fleeting, flickering presence of a good actor from the “outside.”