History remembers her as an event- a beautiful woman seized by a crowd of Christian zealots, stripped naked, and then hacked to pieces. A frightful event, Hypatia of Alexandria, may be even befitting for a woman who was opinionated, remained determinedly celibate, confronted one of her influential suitors with her used menstrual pad to show him how beauty and the unclean cohabited. But Hypatia was more- she was a mathematician, an astronomer and a neo-Platonic philosopher- although these are matters of less importance.

A study conducted by BiasWatchIndia, between June 2020 and December 2021, has revealed that only 13.5 percent of the faculty members across 98 universities and institutes in the country are women, which curiously dips further as we focus on the top-tiered institutes like Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and Tata Fundamental Research (TIFR).

While using the Bengali idiom, ‘Khana r bachan’- which stands for rightful prophecy- how many of us probe into the name to whom the spoken word is attributed? Khana is generally considered as a poet who composed agricultural and everyday rhymes in Bengali during the medieval times. But that the rhymes revealed an inherent sense of the planetary world, mathematical calculations that led to predictions, knowledge of the seasonal cycles is almost silenced. When Khana emerged as a threat to her famous astrologer father-in-law, Varahamihira of Chandragupta-II’s Nabaratna Sabha, she was forced to cut her own tongue, putting an end to her ‘bachan’ or spoken word.

What connects Hypatia and Khana are their extraordinarily agile minds that dwelled on complex calculations based on acute observations of the planetary world, which posed distinct threats to the male-dominated institution of knowledge so that they were eliminated early on and their contribution stunted as ‘womanly’ and peripheral.

Women like Marie Curie or even Kadambini Ganguly, the first Indian woman practitioner of western medicine, seem to carry the legacy of Hypatia and Khana in the way they have struggled to be recognised for their contribution in the patriarchal field of science, while constantly being criticised for their performance of womanly responsibilities of the family. There is Abala Bose who, although illumined in the borrowed light of her scientist husband, Jagadish Chandra Bose, was herself a notable feminist who was denied admission to Calcutta Medical College in 1880s.

One is reminded of Woolf’s ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ who still stands as an apt metaphor of what a woman could be had she been given a chance. But women have often had to take extreme measures for a chance in every walk of life, and more so in fields related to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) which seem to be guarded by gatekeepers of patriarchy. Kamala Sohonie, after graduating from Bombay University in Chemistry and Physics in 1933, had been denied research fellowship by Nobel laureate C.V. Raman because she was a woman. She is said to have responded to the rejection by holding a ‘satyagraha’ against Raman.

Kamala Sohonie, after graduating from Bombay University in Chemistry and Physics in 1933, had been denied research fellowship by Nobel laureate C.V. Raman because she was a woman.

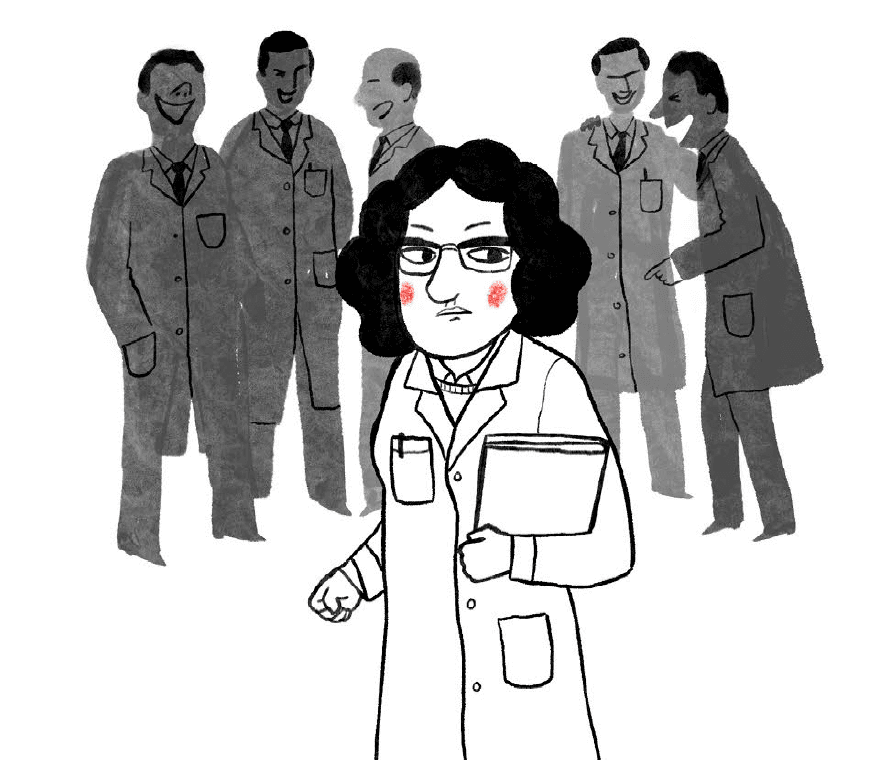

Raman was forced to accept her application but also made every effort to stunt her potential by levying conditions on her free movement in the laboratory, her claim to recognition. Although she forced Raman to recognise her potential which led to the Indian Institute of Science opening up its gates for women researchers, that she had to endure humiliation at the hands of a ‘great’ scientist reflects the extent to which Indian research institutions are thoroughly influenced by the dominant gender biases that operate within society, biases that invisibilise women’s contribution, biases that are prevalent to this day.

Women workforce participation in STEM

It is interesting that while India exhibits a higher rate of women’s enrolment in STEM courses at the graduation level than many other countries, only 29 percent actually join the STEM workforce of which only around 3 percent women hold CEO positions in the STEM industry. A study conducted by BiasWatchIndia, between June 2020 and December 2021, has revealed that only 13.5 percent of the faculty members across 98 universities and institutes in the country are women, which curiously dips further as we focus on the top-tiered institutes like Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and Tata Fundamental Research (TIFR).

Invisibilisation of women in STEM research further deepens as they are overlooked at STEM conferences while high attrition is noted as their careers progress. The researchers, Shruti Muralidhar and Vaishnavi Ananthnarayayan attribute these troubling statistics to the lack of ear marked resources, the will and commitment of the leadership in Indian science agencies and universities towards equity, while also calling out to a general lack of awareness and understanding of the problems of women and minorities in STEM. Besides, women are also subjected to the continuous working of implicit and explicit bias in all professional spaces.

The bias works in such a way that while the representation of women in the engineering faculty is the lowest, biology, which is regarded as ‘soft science’ has the highest representation of women as compared to chemistry, physics, and computer science. The researchers opine that the percentage of women among earth sciences and maths faculties increase only when top ranking institutes were merged with state universities. While this might seem to be a reflection of government policies that aspire women-led development which could help realise the core of India’s G20 agenda of women’s economic empowerment, the transition from policy to practice seems to have been problematic at various levels.

The study has recommended regular gender audit at HEIs which should be publicly displayed so that trends can be tracked and the future goals towards equity can be set.

Of course, the researchers agree that as universities ramp up measures for inclusive representation, more women are joining as faculties in universities and institutes, but it does not mean that the scenario has changed drastically or shows much possibility of change. The study has recommended regular gender audit at HEIs which should be publicly displayed so that trends can be tracked and the future goals towards equity can be set.

Reasons for missing the mark

It is indeed bewildering that when India’s STEM research bespeaks of immense potential, it actually functions within such contradiction as the underrepresentation of women. While with the launch of Chandrayaan-3 lunar mission women scientists of ISRO were harked as path breakers of the future, this report seems disconcerting, although not unbelievable.

One might even question-why would the report garner attention at all? Isn’t it stating the obvious- non-participation and invisibilisation of women in higher education and research at Indian universities and institutes which have been standing as male bastions since times immemorial? The history of these institutes has literally been his-stories where stories have moved from man to man. While this study focuses on STEM research and teaching, any woman researcher and faculty from non-STEM disciplines would definitely be able to relate to the outcome of the study.

Delving deeper into the report will evidently reveal how a complex tapestry of societal expectations, inadequate guidance to girls at primary and secondary levels, family pressures, marital age clashing with research prospects, myth of work-life balance, secondary status accorded to women’s work along with continued objectification of women and the ensuing violence coagulate to create formidable roadblock for women in any field. Women are expected to continuously provide proof of their potential, which is again systematically downplayed.

As such Mitra Jyothi, Vanitha Muthaiah, Nigar Shaji, Tessy Thomas, or even Rohini Pande cannot become house-hold names since their achievements and contribution for the nation do not suffice for Indian standards of advertising where the concept of attractive woman remains unchanged.

Lack of awareness of governmental and non-governmental initiatives also emerges as a major factor for the diminishing numbers of women in STEM research and practice. Underrepresentation of women and girls in STEM has been an ongoing concern for policy makers in India. Studies have shown how policies and programmes like WISE-KIRAN, GATI, SERB-POWER create avenues for women to participate and grow through STEM research.

Studies have shown how policies and programmes like WISE-KIRAN, GATI, SERB-POWER create avenues for women to participate and grow through STEM research.

However, it should be remembered that opportunities are not free from constraints that emerge with respect to accessibility and affordance. The need to propel an inclusive education and research ambience requires not only attentiveness towards STEM research initiatives, but also towards the integration of arts within STEM, so that STEAM evolves as the new crucible for knowledge production. Such an initiative can dismantle barriers while fostering creativity within critical thinking.

Time to rethink

All of this directs attention to the need to rethink. This study serves as a reminder that women’s empowerment is still an unfinished project. It will continue to remain so until society accommodates smaller changes and continues to build on them, especially within HEIs. It is important for HEIs to evolve as spaces which can self-assess and realise that they are not above and beyond societal prejudice, neither are these disconnected from society. As institutions of learning, these spaces must strive to emerge as vanguards of dismantling stereotypical ideas and fostering change both within and without.

Instead of considering themselves as secluded, bordered communities, its time HEIs realise their responsibility and comingle with society to create a difference in the way society defines “success” and “power”. These spaces should emerge as feminist spaces which can dismantle the working of hierarchies at all levels, can foster an ambience of collegiality and kindness in academia. Only then will academia be able to accommodate insecurities and fractures, using its transformative capital to ensure growth and empowerment.

About the author(s)

Priyanka Chatterjee is a mother, researcher, and academic. She lives and writes from Siliguri. Her articles have appeared in Feminism in India, LiveWire, Himal Southasian, Sikkim Express, among others. She can be reached at site.surferpc@gmail.com and is on Instagram @priz_chatt