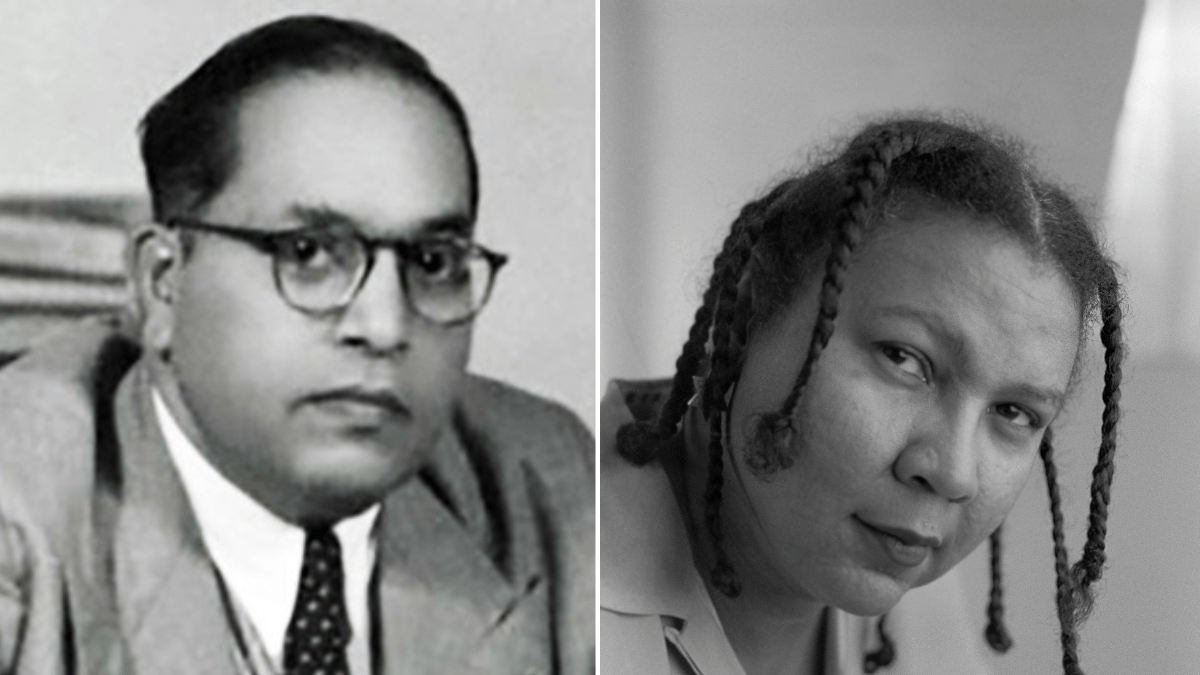

‘The practice of love is the most powerful antidote to the politics of dominance,’ writes a passionate bell hooks, as she reminds us that all the great movements for social justice in our society have a firmly rooted love ethic. She reminds us that if we are to create a loving culture, profound changes in how we think and act must occur. We need a culture where we love and let our hearts speak. So how do we achieve that?

When bell hooks takes love outside a heteronormative sense of romantic bond and places it in different contexts within our society, our relationship with anything within and around us profoundly changes.

To begin with, let us think of love as an action rather than a feeling. This is one way in which anyone using the word automatically assumes accountability and responsibility. When bell hooks takes love outside a heteronormative sense of romantic bond and places it in different contexts within our society, our relationship with anything within and around us profoundly changes. Perhaps this is the bare ground for any social democracy to thrive. This brings us back to what Babasaheb Ambedkar had once preached in the realm of social ethics.

He often stressed how if democracy is just a political competition between self-interested individuals, it will never succeed in bringing about liberty, equality and fraternity. So, how do you draw that fine line between individual liberty while also ensuring equality and solidarity?

Democracy and love

Borrowing an example that Jean Dreze states in his essay ‘Dr Ambedkar and The Future of Indian Democracy’, let’s consider the problem of urban destitution in India — the plight of wandering beggars, street children, leprosy patients, the homeless and others. These people constitute a small minority and possess zero political power. These people don’t vote and are not likely to vote in the future. Their problem could come within democratic politics, only based on ethical concerns. That is, if social ethics acquire a central role in democratic politics, a new world may come into view.

Contrary to popular sentiments, Dr Ambedkar was speculative about the definition of democracy being the government of the people, by the people and for the people, as he asked, ‘What kind of people are we talking about? Are they rational or irrational? Are they tolerant or intolerant? Are they equal or divided into castes? Are they compassionate or full of hatred?’ All this shapes the outcome of the government ‘by the people’. He called democracy a ‘mode of associated living’ and held it close to his vision of a ‘good society’ based on liberty, equality and solidarity. Through this process, he also teaches us how to think critically and examine our own values. He dreamt of democracy as a form and method of government whereby revolutionary changes in the socio-economic life of the people are brought about without bloodshed.

Reimagining the world order

While Babasaheb imagines a world order with ethics binding hand in hand with humans, bell hooks takes us on a ride for inner exploration to achieve the same. Through a detailed analysis of love ethics- one shaped by grace, clarity, justice, honesty, commitment, spirituality, values, greed, community, mutuality, romance, loss, healing and destiny.

‘Knowing how to be solitary is central to the art of loving. When we can be alone, we can be with others without using them as means of escape.’

bell hooks

hooks’s ‘love ethic’ requires work and intentionality. It demands one to foster mutual respect and understanding in relationships, whether they be romantic, familial, or platonic. Her love ethic is grounded in every individual’s inherent worth and dignity. She believed in the agency attributed to the lived reality of a human.

On this line, Babasaheb, in his last book, The Buddha and His Dhamma, denotes a fine distinction between vidya (knowledge) and prajna (insight), realising the importance of non-scientific modes of learning, just like how trying to explain the emotions evoked by a piece of music using rational arguments falls short of the experience of listening to it. However, it never sought to distract one from the rationality in individual enlightenment and social living.

Remarkably, hooks’ love ethic calls for dismantling systems of oppression such as racism, sexism, and classism. At the same time, Ambedkar’s social democracy aims to address caste-based discrimination and inequality in Indian society. His morality emphasises the importance of recognising and upholding the rights and dignity of marginalised communities by acknowledging each other’s agency to tell their story and stand tall.

Ambedkar and bell hooks’ rallying cry of love

‘You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world, and you have to do it constantly’, says Angela Davis, kindling the spark. Reading bell hooks and Ambedkar are unadulterated representations of this energy in its most authentic forms.

The language of hooks is a lullaby, nurturing each of us like we were children, teaching us the transformative power of care. In the meantime, she also turns it into a sword that cuts through various social ills that promote tyranny and hierarchy. hooks’ love ethic is a concept that is based on a deep understanding of each person’s inherent worth rather than just affection. Ambedkar’s goal is depicted in this image as empowerment, a way to free oneself from shackles of caste and create a society where everyone can walk with dignity.

‘Without equality, liberty would produce the supremacy of the few over the many. Equality without liberty would kill individual initiative. Without fraternity, liberty and equality could not become a natural course of things.’

Dr. B R Ambedkar

As these two visions converge, a radiant light is cast upon the societal structures that govern our lives. Their shared commitment to justice and equality finds its fullest expression amidst the corridors of power and privilege. Perhaps the most forgotten aspect of suppressing dissent is that it always resurfaces with more vigour. Something that the power structure frequently overlooks in terms of the global uprisings against injustice and oppression. They feel nothing but honour for the cause they stand for, and each act of threat the system throws at them serves as evidence of their steadfast commitment to it.

It is a call to action, a rallying cry for change, as they dare to dream of a world where compassion reigns supreme and every voice is heard. So next time you come across the works of hooks or Ambedkar in libraries, academic conferences and protest grounds, remind yourself of the immense potential of our human hearts and the undying force of hope it holds.

References:

- All About Love — bell hooks

- Dr Ambedkar and The Future of Indian Democracy — Jean Dreze [The Radical in Ambedkar]

About the author(s)

Fathima Althaf is a student of Development Studies at TISS Mumbai. She considers herself a product of many communities she has been part of, ranging from technical organisations to non-profits

Interesting parallels drawn.Loved it!