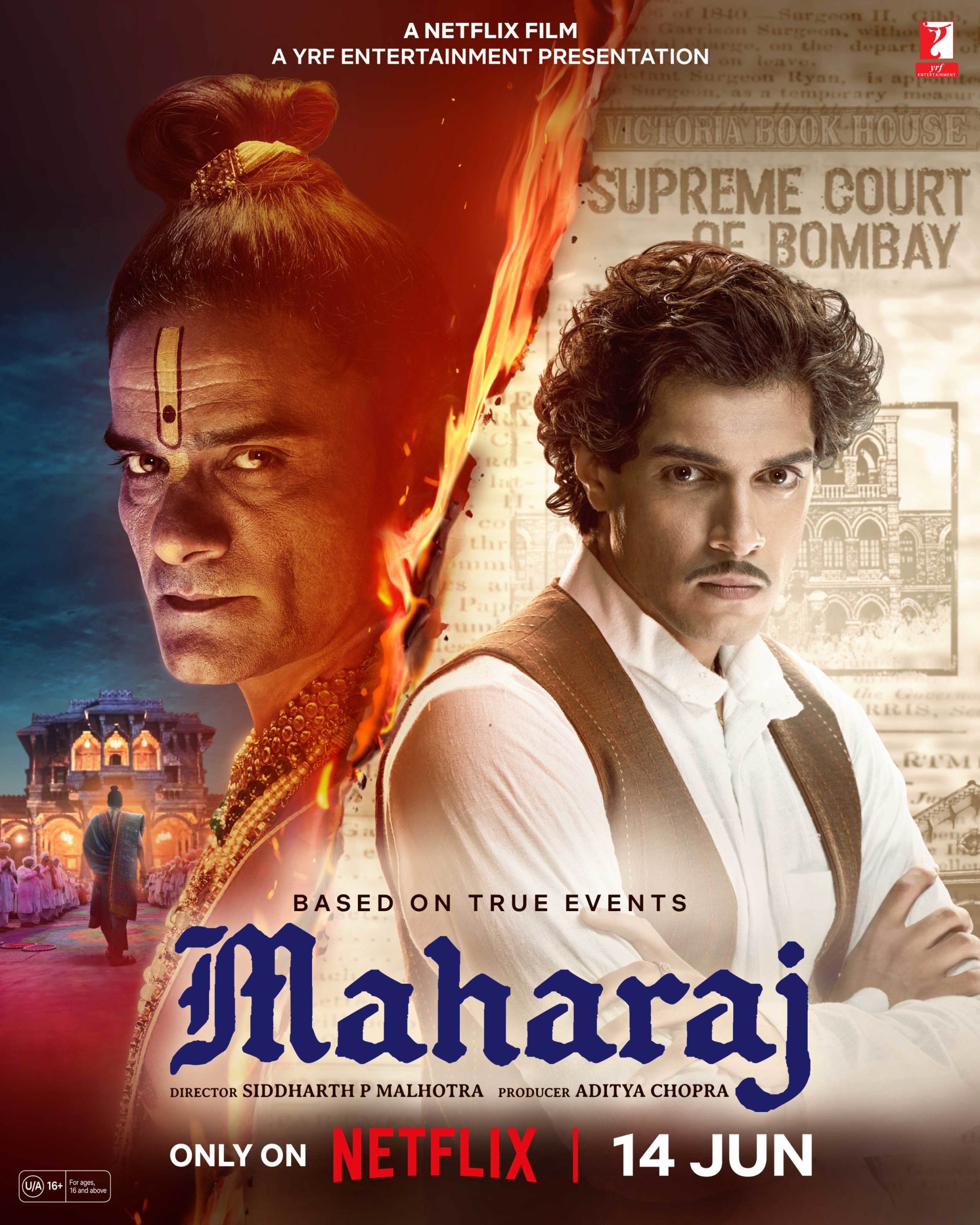

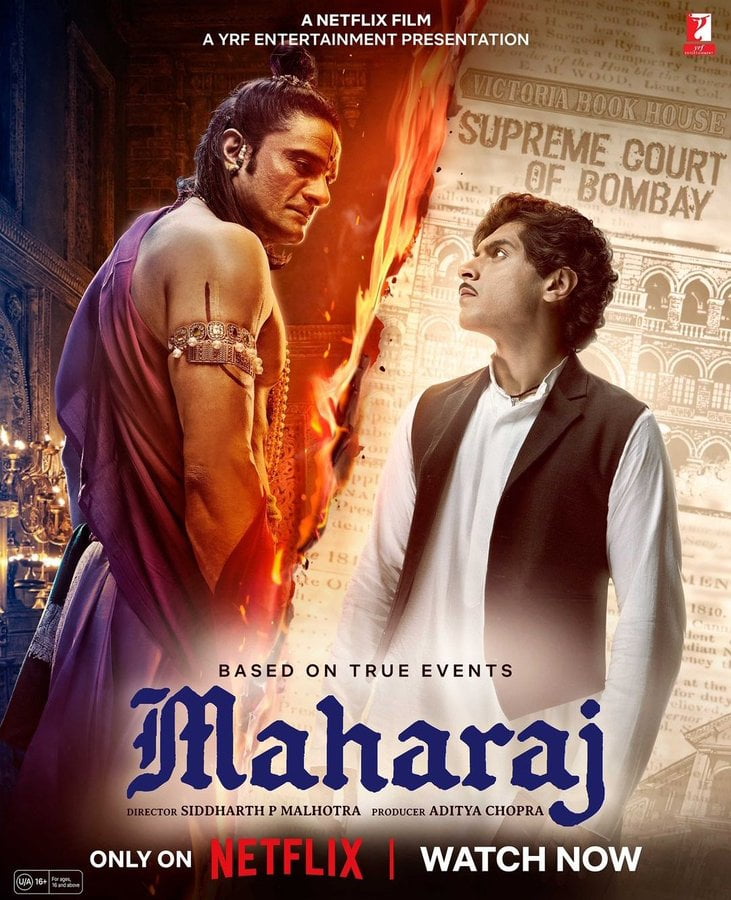

‘Socha hain kya hoga us din jab bhakto ko pata chalega ki bhagwan toh is haveli se ja chuka hain.’ retorted a surprisingly sleek manifestation of Aamir Khan’s son Junaid at the smug face of Jaideep Ahlawat’s despicable JJ. Fresh after the election frenzy and watching religion getting juggled for a few seats in the parliament, it is difficult not to smirk at the pinch of subtext. Maharaj, a retelling of the infamous 1862 trial of the Maharaj Libel Case, is a curiously bland recipe despite fiery ingredients. But all is not lost as Jaideep Ahlawat delivers a cold and disgusting godman effectively and the subtext of India’s current relationship with religion, journalism and politics creates a momentary stir.

‘Dharm ke thekedar’: both believable and deplorable

Jadunathjee Brajratanjee Maharaj was at the peak of his power as a religious leader when an article written by Karsandas Mulji attempted to dethrone him and by extension his likes. The article in question was titled ‘Hinduo No Asli Dharam Ane Atyar Na Pakhandi Mato’ (The True/Original Religion of the Hindus and the Present Hypocritical/Phoney Sects) that questioned the values and customs of the Hindu Vaishnavite sect called Pushtimarg, of which Jadunathjee was the leader. It accused Jadunathjee of having sexual liaisons with female devotees and further manipulation of family members to offer their female family members. The accused Maharaj took the desperate step of going to court, charging Karsandas with a defamation or libel case. This is the historical premise upon which Siddharth P Malhotra mounted his recent film – Maharaj.

A period drama is a tall ask from YRF but Aditya Chopra seems to be enamoured by the same despite Shamshera’s catastrophic failure or Samrat Prithviraj’s constipated presentation. Maharaj lives up to that reputation as it drags its feet in establishing a compelling backdrop from the get-go with shoddy VFX to jarring costume design, almost anachronistic. Within the first few minutes one wonders if the Bhansali fever is upon every producer in this country – from Karan Johar trying to pull a Kalank to Maharaj’s first female lead dancing to familiar Ram-Leela-esque beats and choreography – it is a fever dream that refuses to end.

Within the first few minutes one wonders if the Bhansali fever is upon every producer in this country – from Karan Johar trying to pull a Kalank to Maharaj’s first female lead dancing to familiar Ram-Leela-esque beats and choreography – it is a fever dream that refuses to end.

But in the first few clumsy and hurried steps, there is a surprising glimpse of conscious subtext as young Karsan questions everything around him and draws the audience’s attention to secondary divinity bestowed upon sect leaders, etched on the temple or haveli walls alongside idols of Hindu gods.

Jadunathjee Maharaj has been Lucifer-ised in this version of the story – a buffed-up Jaideep Ahlawat steps boldly into the role of Maharaj alias JJ. The setting of Mumbai in the 1860s and the rockstar-like nickname “JJ” causes an uncomfortable dissonance that one does not recover from through the length of the film. Ahlawat effortlessly paints JJ as a cold, self-assured and arrogant menace. As “dharm ke thhekedar” he is both believable and deplorable – with some of the best dialogues to his credit. Despite trying to create an image of a religious man in the light of decadence, Siddharth fails to create the contrast that is supposed to draw the ire of the audience.

One wonders what was the point of a Bhansali-meets-Lucifer scene where Ahlawat’s JJ saunters out of the pool, sopping wet – dhoti and all. From JJ feeding his pregnant devotee cum prey a datura-laced laddoo to him refusing to swear on The Gita – Ahlawat delivers the best he can on shaky grounds. The bad priest must always have a good priest to create the necessary yin to the yan. Lalvanji Maharaj is a silent and displeased priest who secretly wishes to overthrow JJ. Despite memorable dialogues like ‘Sawal na puch sake wo bhakt adhura, jawab na de sake wo dharm.’ it is evident in the placement of these bumper sticker lines that the director did not know what he wanted to focus on – the political subtext, the revenge story, the romantic offshoots, the social reformists of the 1800s or nothing at all.

Maharaj goes from widow remarriage to untouchability to women’s education

Siddharth P’s career in television inadvertently shows in the storytelling as the bejewelled sets and equally decked women of the film fail to transpire urgency even in scenes of consent manipulation and sexual favours drawn by a guru from his devotees. It is infuriating as the contemporary relevance of such a story and a topic as nuanced and important as consent manipulation is failed by clumsy direction and a painful need to focus on the debut of a star’s son. The declaration of values in the new Bollywood woke wave is distinctly boring and laughable.

At the onset, before one can make sense of the setting of the film, Karsandas comes forth and declares himself a feminist reformer. From Manju’s monologue in Lapataa Ladies to Rocky aur Raani’s listicle of feminist concerns – it is tiring to see Bollywood struggle with the basics of storytelling – show, don’t tell! Now that our feminist, wide-eyed Karsandas has been set loose in the story, he goes forth to show us how he fails his fiancee, displaying a self-centred and feudalistic anger towards losing what was supposed to be his – her “virtue”.

In establishing Karsandas as the reformist and idiosyncratic hero, Maharaj tries to address a list of issues in small perfunctory gestures – from widow remarriage to untouchability to women’s education.

In establishing Karsandas as the reformist and idiosyncratic hero, Maharaj tries to address a list of issues in small perfunctory gestures – from widow remarriage to untouchability to women’s education. But it fails to establish a significant part of the story’s foundation – the sect that Jadunathjee Maharaj leads – the cotton traders of Gujarat who moved to Mumbai. The economic and political context of that community would have added the necessary depth to the story and the complex relationship between devotion and money.

The subtext of intrigue in the story, more than in the telling, is the conflict between an authoritarian power – here religion, and journalism. The choking of voice, as the first prints of Karsandas’ paper are burnt by JJ, touches a familiar chord. This effect cannot entirely be credited to the direction or storytelling. In the last couple of years the way our country has seen a clampdown on the free voices of journalism, anyone who cares for the fourth pillar of democracy would resonate with this aspect of the film.

JJ confidently tells Karsandas as the latter promises to bring the former to justice, ‘Aaj ka lekh kal ka raddi hota hain, Sanatan sirf dharm hota hain.’ The country’s regime is equally confident that religion and blind faith shall overtake news-making and journalism. The kinship and peer support received by Karsandas from Dadabhai Naoroji and his contemporaries is a breath of fresh air. Maharaj did not give enough space for their sharing of ideas or contemporary challenges of running presses under the British regime – but it does nudge one’s imagination in that direction.

The women of Maharaj: failed depictions

Last but not least, the crowning glory is Junaid Khan’s debut. Aamir Khan’s son delivers a lack-lustre but consistent Karsandas Mulji. His Gujarati-laced Hindi was a commendable show of effort. As the film progresses Junaid has a better grasp of the character, even though he fails to bring the audience’s blood to even a simmer. Karsandas is strangely wide-eyed throughout the film – be it anger or love. There are moments in Maharaj where one gets a glimpse of intensity, a promise of a better performance. One shall have to lay some of the blame at the director’s door as the confusion of the storytelling reflects on the protagonist.

At best Junaid’s woody Karsandas is a forgettable debut and not disastrous. The two female leads are rather mawkishly written. They are accessories to a story – one consequential, another merely a foil. Shalini Pandey does her best as Kishori- the innocent devotee, while Sharvari Vagh’s Viraaj is the most irritating version of a classic YRF “bubbly girl-next-door” heroine. To her “haan ki haan?”, a decided no! For a film that operates on the plight of women, it tragically fails its two main characters. There was ample scope for the story of JJ’s wife to find a place in the narrative but in the limited space, Meher Vij performs with a lot of steely grace.

As young and old women enter the doors of the haveli for “charan seva” and voyeurs take the pleasure of second-hand moksha – Maharaj should have been able to elicit an angry reaction from the audience. Yet the effect is quite anti-climactic and damp. It almost makes a mockery of the victims as well as a contemporary feminist movement as women stand up in the courtroom saying “me too” or “main bhi” after Karsandas’ aunt comes forth as a survivor of JJ’s abuse.

Even though this case was a landmark judgement in Indian history and is a rare win of truth over power – Maharaj could neither inspire rage nor satisfaction.

Even though this case was a landmark judgement in Indian history and is a rare win of truth over power – Maharaj could neither inspire rage nor satisfaction. The film does succeed in making one angry for failing to tell such an important story at such a significant time with any memorable effect.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo