‘His fingernails are ragged. He wears posh designer suits, but his choice of underwear- tight and white reminiscent of something a little boy would wear is soul-stirringly evocative. When he is inebriated, he talks about Stalin, and he does not know how to unfasten garters.’

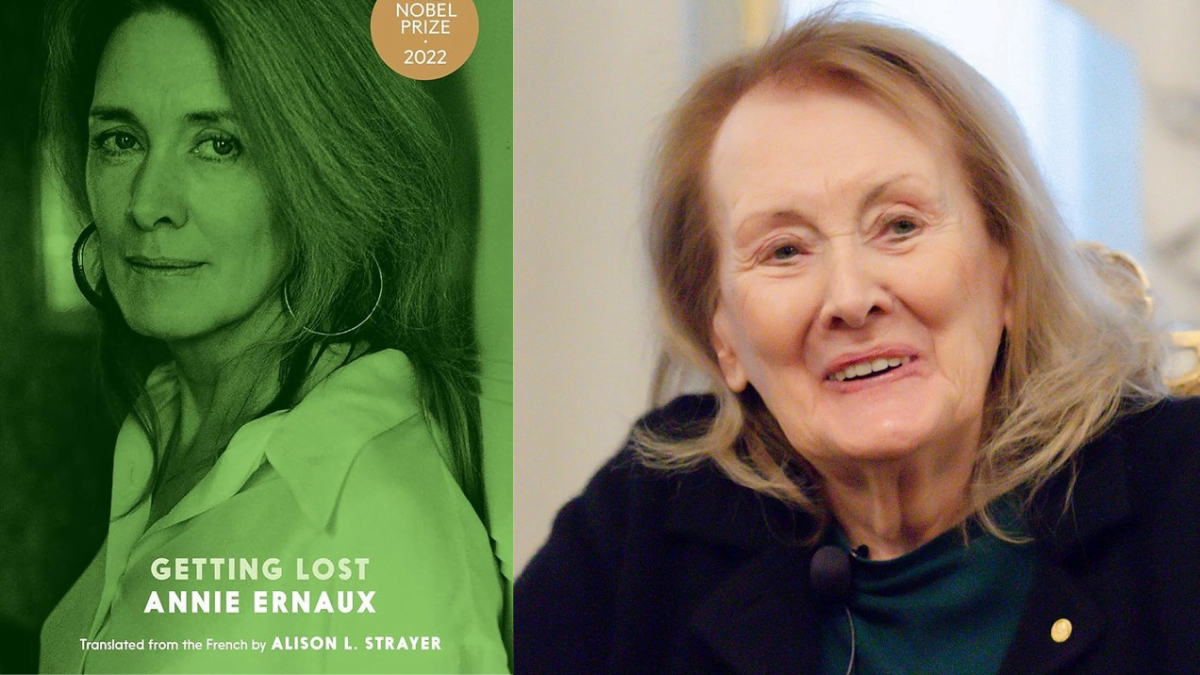

Her book Getting Lost reads as simple journal entries from her late forties, as she has an affair with a married Soviet diplomat in Paris.

When Annie Ernaux won the Nobel Prize for Literature in the year 2022, she was lauded for her courageous and brave writing. Whilst this sounds like an achievement, most people never understood the gravity these worlds held. After reading their first Ernaux novel, however, people usually feel an insurmountable amount of emotions.

Her book Getting Lost reads as simple journal entries from her late forties, as she has an affair with a married Soviet diplomat in Paris. The amount of sex they have is impressive and described with a raw eye for detail.

What makes the book as touching as it is, however, is how she speaks of how she feels. Love, as we’ve heard of it, is ideally supposed to blanket us with security and safety, but S (her lover), does exactly the opposite as she spirals into obsession. The book is a miracle because it talks about the ugliness of love alongside everything else – how loving is a game of simply waiting, waiting for someone else to call back, to write, to visit, to acknowledge your existence to make you feel seen?

The bold rawness of Annie Ernaux

Ernaux’ desperation through the pages is palpable and it is her directness that makes us feel not like voyeurs, but witnesses as if we too are experiencing the exact same thing. Astonishingly enough, when we’ve been in love, we have felt the same itchiness to just return to the sight of our home, our lover- our dream-house that can shatter us or secure us with all its volatility. Her sentences make us face emotions that we often repress in order to conform to the expected morality of society, and when she writes, she is certainly not the sort of woman who goes flower- picking every morning, but embraces all the thorns.

Getting Lost is raw and dark but without reprieve or salvation- we forget that we are reading her diaries and not a work of fiction. To console herself and feel more seen in her predicament, Ernaux reads and revels in Anna Karenina, comparing herself to Anna and S to Vronski. She acknowledges her insecurities- that S fetishes the idea of her, of being with a French writer and an older woman rather than really wanting to see her in her wholeness.

The constant terrors of being broken up with every day she doesn’t hear from him shatters Ernaux and then fills her up.

The constant terrors of being broken up with every day she doesn’t hear from him shatters Ernaux and then fills her up. Her obsession with this man is exhausting; it is as though her thoughts make up the entire relationship.

The book is about loneliness, but at the same time it is a siege of desire, a war of love. Interestingly, even though Ernaux plays the role of “the other woman” – essentially one destroying a family, we never look at her that way. She is in so much agony herself, that all she seemingly needs is empathy.

The play with memory

What appeals to a reader isn’t necessarily that her boldness is endearing; wretched obsession infrequently isn’t. It’s that she writes in a manner that impales you with a knife. Ernaux writes of wrecked scenes of love, of being so compulsively in love with a man that she wants to sleep with tangible sperm underneath her pillow. She loves it when he comes on her belly, it’s a memory she cradles for the rest of her relationship and especially in all the moments when she waits for him.

An interesting notion is how she tackles memory. Once again, since the novel is nothing but a diary it’s almost horrifying to see how unexpectedly certain instances of her past crop up- it doesn’t seem like she represses any thoughts or is afraid to face herself. Ernaux writes continually of her mother who frequently appears in her dreams, both when she was babbling and incoherent, suffering from Alzheimers’, and from the love she shared with her in the past.

She’s also unafraid to refer to the summer of 1963- a particularly painful year for her as it’s the one when she has an abortion.

She’s also unafraid to refer to the summer of 1963- a particularly painful year for her as it’s the one when she has an abortion. Ernaux’s abortion was in Paris at a time when terminating a pregnancy was illegal, and so she had to figure out a way to do it herself, nearly getting killed in the process. She remembers: the ‘death in her belly’ as she refers to it, haunts her dreams, the ghost of her child making her weep in a manner similar to Toni Morisson’s Beloved. The depression she fights after battling the horrific abortion alone haunts her too, it is what she compares the worst of her sadness too.

To conclude: Getting Lost is relentless in its exploration of falling in love, and memory. It’s a frantic devastating novel, but one that will make you feel more seen and understood with each page.

About the author(s)

Treya covers art, culture, climate and the environment. She has aspired to be a journalist ever since she was little. She has reported for The Hindu and Deccan Chronicle among others and explores how feminism takes root in everyday life by leading sessions with young people on gender, digital safety and the "good girl" syndrome.