“Was that why, even stripped of her freedom and faced with the possibility of having to live out the rest of her life here, she seemed so satisfied, exuding such potent femininity?” Rika Machida thinks to herself as she interviews Manako Kajii, nicknamed Kajimana, a convicted serial killer, who now awaits life in prison.

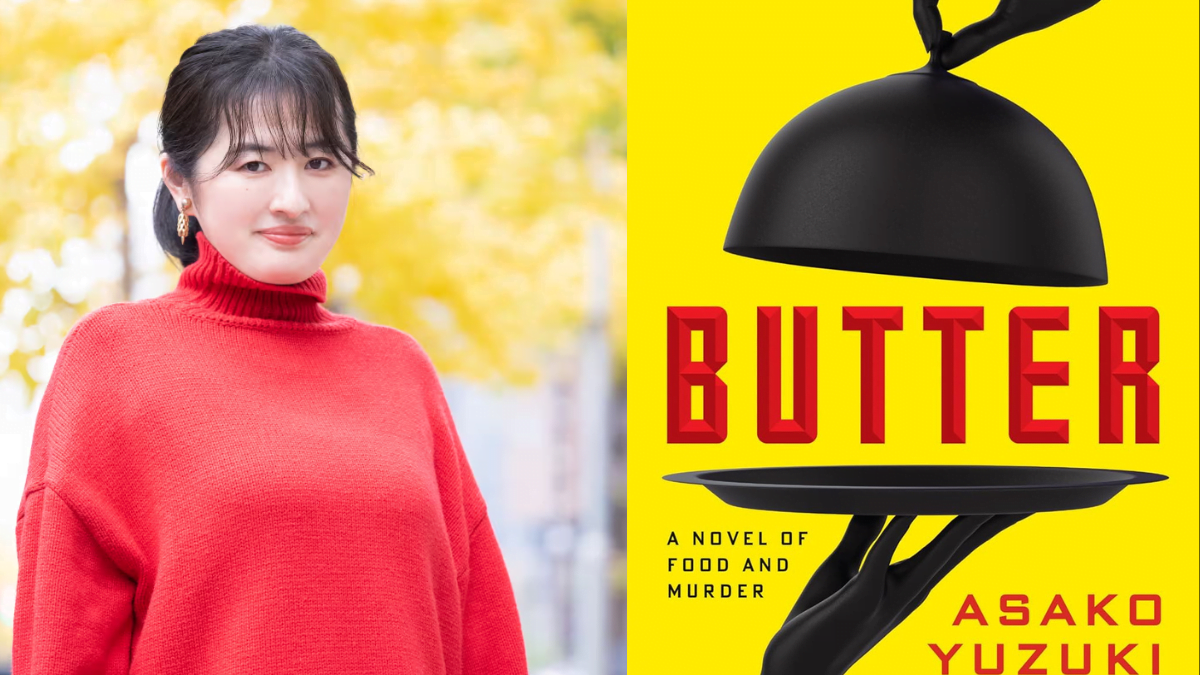

Butter (2024) by Asako Yuzuki, translated by Polly Barton, explores the dynamic between two women, Rika Machida, and Manako Kajii. With lines like “Men gaining weight is different from women,” Butter takes a scalpel to the underlying misogyny and fatphobia that is prevalent in Japanese society, and shows us, the readers, an often underexposed side to our psyche: how far do we condone our fatphobia?

The food and the plot

The premise of Butter is simple; journalist Rika Machida, after a promotion at her newspaper, the Shūmei Weekly, and being “the first woman to make the editorial desk,” asks for an interview with Manako Kajii, a convicted serial killer at the Tokyo Detention House. It is the scoop of a lifetime, and Kajii’s refusal to meet with any other journalist to discuss her apparent crimes has made her even more of an enigma.

Rika has been refused twice, but on her third try, she takes the advice of her friend, Reiko, and asks Kajii for her beef stew recipe. Kajii replies, complying with the request for an interview, and thus the two women embark on a relationship that is far from ordinary, and quite beyond that of an interviewer and an interviewee.

While the official classification of Butter is that of a thriller, food is crucial to the way characters operate throughout the novel. Kajii ‘entraps,’ her victims through her cooking, and Rika steps into the world of gourmet cuisine after meeting Kajii. Butter explores each character’s relationship with food and with cooking as integral to their character arcs.

In the beginning, we see Rika having dinner with her friend Reriko and Reiko’s husband, Ryōsuke, consisting of foods that are beneficial towards pregnancy and conception, “Bagna càuda with a plentiful variety of steamed winter vegetables and a rich anchovy sauce, thinly cut slices of warmed salt pork, a tofu and leek gratin, rice cooked in an earthenware pot with vegetables and chopped oysters, and miso soup.”

In the end, she hosts a Thanksgiving dinner party, with people she knows and loves. Rika’s initial impression of food is simply to subsist on. In the middle of the narrative, she realises, “eating, was fundamentally an individual and egotistic compulsion.” Kajii’s love for gourmet food was her egoism showing through. Rika realises that Kajii and her cooking, which had an irresistible pull on anyone who consumed it, was not because she was making it with said person in mind, but simply because she wished to have it herself. The desire to please her paramours was entirely absent in Kajii, which is perhaps why it made her all the more attractive to them, as well as to Rika. Her attraction towards Kajii begins on the academic, and veers into a sapphic territory, which remains unrealised till the end.

Even as Rika interviews Kajii, her imagination becomes explicit, “A picture floated into Rika’s mind of Kajii stark naked, her huge breasts pressed together and her chin thrust forward to fit her nipples into her mouth. This woman wanted to eat herself whole.” Kajii becomes the object of desire for many people, Rika included, by simply refusing to conform to the societal standards of what it means to be desirable.

Butter’s protagonist is Rika, to be sure—it is her thoughts that we read and are aware of, and we view every other character through her eyes—but it is a story of women, and Japanese women in particular. Butter is incisive, and it exposes the impossible standards Japanese women, and indeed, women all over the world, are exposed to daily, “Japanese women are required to be self-denying, hard-working and ascetic, and in the same breath, to be feminine, soft, and caring towards men, everyone finds that an impossible balance to strike, and they struggle desperately as a result. Even when they do manage to strike it, there is no redemption to be had. They are never fully free.”

Kajii’s impassioned monologue invited the reader to wonder, what exactly are these impossible standards that we as women ourselves, hold us to? If we turn our gaze to India, we might find ourselves in a not-too-dissimilar situation, where women are held to impossible standards by the patriarchy and by other women with internalised patriarchy and misogyny, who see it fit to inflict these tortuous standards on the next generation of women, simply because they have suffered, and want others to be subject to the same fate.

The pressure that is put on Rika to exercise, and to diet, both by Makoto and by Reiko—Reiko tells her “You don’t seem to have any motivation to exercise, either,” and Rika thinks of Makoto’s desires, “What was it that Makoto wanted if not a woman slender as a board who never said anything troublesome, didn’t tie him down, and wasn’t in any way too much for him? Would he not, in fact, drop her with surprising abruptness if she failed to meet even one of those requirements?” is it not the whisperings of patriarchy telling Rika, and by extension, women, to be less like and more like dolls moulded by the expectations of patriarchy and its enforcers?

Is patriarchy simply a system by which men subjugate women? Or is it an all-pervasive creature that seeps into our daily lives and refuses to let go? Rika’s desire for Kajii is also based on subjugation, not on camaraderie, “Rika was overcome by a desire to subjugate the woman sitting before her, separated only by the acrylic screen. The urge to touch her, to dig her fingers into that huge bosom, took her with startling force.”

Desire in Yuzuki’s writing always comes with a need to either subjugate or be subjugated. Rika knows nothing outside of this dynamic, which is why she views Kajii as an anomaly. Manako Kajii, by all accounts and reports, is a woman whose desire should be to submit. She admits that she hates other women, hates feminists, and above all, hates the idea that women should be independent—but Kajii, in her desire to be submissive, is the dominant one in all her relationships. When Rika expresses her desire to be Kajii’s friend, she responds, “I don’t need friends. I’m only interested in having worshippers.”

Manako Kajii and Butter

What does it mean to be worshipped? What first comes to mind are Petrarch’s sonnets, written for his beloved Laura, with lines of flowery language, “Breeze, blowing that blonde curling hair,

stirring it, and being softly stirred in turn, scattering that sweet gold about, then

gathering it, in a lovely knot of curls again.”

Petrarch places Laura on a pedestal that he is far beneath, deifying her in a way that takes away all her agency, reducing her to an object of worship. Similarly, Kajii’s admirers also worship her; however, their worship is tinged with an air of disgust, pity, and the knowledge that being with Kajii reinforces their “manliness.”

A quote given by the sister of Kajii’s third victim, Yamamura, stands out, both to Rika and to us, “As I said in court, he always spoke badly of her in front of me—saying she was ugly, or fat, or strange and naive. As a woman, it was horrible to hear him say those things. But I could tell that that was just all talk, and actually he was crazy about her.” Kajii weaponises her femininity in a way that is so unfamiliar for Rika, and for us, that it makes her into an object of naked interest and desire. Keeping in tune with her reputation as a femme fatale, Kajii relishes in this adoration, this worship she receives, even if it implies her dehumanisation.

For Kajii, being worshipped is not dehumanising; she accepts the attention that Rika, like all her victims before her, showers upon her, like it is her birthright. Rika does not understand why she is subservient to Kajii’s whims and desires, nor why the mere presence of Kajii, or her name, irritates Reiko, Kajii occupies the top rung of the ladder of hierarchy, even when, by all standards, she should not.

Food and agency

Butter, as the name suggests, employs food as a third, all-pervasive presence via which we can see individual characters coming into their own. Butter’s brilliance lies in its framing of personal eating habits, which are left perpetually as a mystery to be solved. Both Yuzuki’s writing, stilted in places, flowing in others, and Barton’s translation, breezily moving through the difficult sentiments of the characters, accomplish this Herculean task with ease.

Rika realises halfway through the novel that her eating habits have been consistently informed by other people and that even in trying to understand Kajii and eating gourmet food, what she has essentially done is submit to Kajii’s desires. The act of going to a Japanese bistro with her boyfriend to consume healthy food because she gained weight, is an overt act of taking away her agency; however, when Rika goes to Joel Robuchon’s restaurant at Kajii’s behest, she is doing exactly as the other woman intends for her to do, being subservient to Kajii’s wishes instead of her own. Who is taking away Rika’s agency? Is it Makoto, who takes her to a Japanese bistro for her to lose weight, or is it Kajii, who forces her to bend to her whims and desires?

Butter opens with the story of Little Babaji, where three tigers chase each other round and round until they dissolve into butter, and are then put into a dish. Rika, upon a visit to a dairy farm, wonders, “Milk was originally blood. In that case, was the butter in the Babaji story actually a metaphor for all the carnage that took place under the cover of the jungle? What seemed pure, white, and creamy had its origins in vivid, bloody red – was that not the essence of this whole case?” For Rika, Reiko, and Kajii, their existence is steeped in blood, a smell that lingers even through the richness of butter, one that will not be sweetened, even with all the proverbial perfumes of Arabia.