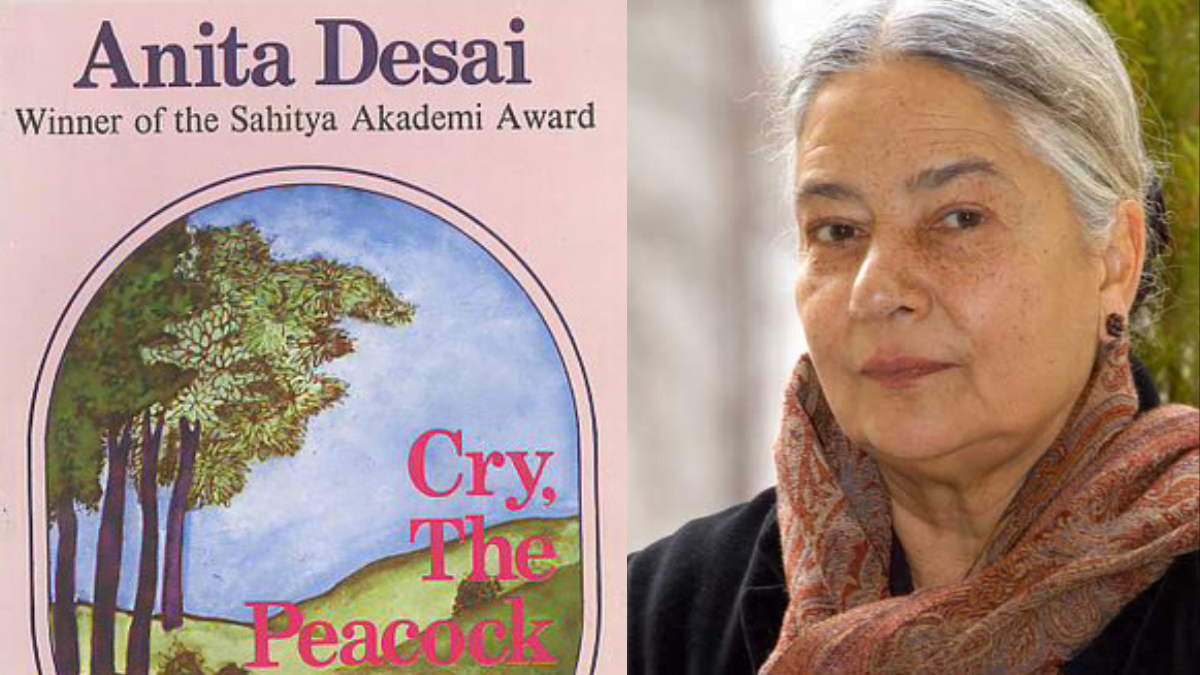

Anita Desai’s debut novel, Cry, the Peacock, is a masterclass in postcolonial Indian English fiction. The reek of a slow-rotting corpse on a sultry April afternoon provides the initial setting for the story. It is with this ominous imagery that Desai entices her audience into the stiflingly languid world of her protagonist Maya.

Maya is a lonely homemaker, struggling to come to terms with her husband Gautama’s cold indifference and the urban apathy that enfolds her middle-class existence. She is constantly prying for fissures in Gautama’s restrained exterior, in hopes of finding insight into his inner thoughts. From the very first chapters of the novel, it is instantly made clear that Maya’s lack of true companionship significantly impacts her emotional well-being.

Cry, the Peacock is a very strange book. It eschews quick resolutions, often swelling and stretching within its thematic musings. Desai executes the slow unravelling of Maya’s psyche with unsparing precision. At its heart, Cry, the Peacock is about a foretelling by an albino astrologer during Maya’s childhood. According to his prophecy, Maya or Gautama would die four years into their marriage. Maya’s obsessive fixation with the prediction soon leads to a strong conviction that she will be the one to die. As time passes, she gradually drives herself to the brink of a cynical neurosis.

The reader first encounters the image of the crying peacock when Maya has the epiphany that the prophecy could equally be about Gautama. In actively transferring her vision of death onto her husband, she concurrently projects her alienation and frustration into a surging hatred toward him. One fatal night, an agitated Maya watches as Gautama comes between her and the moon as “an ugly, crooked, grey shadow.” He takes the horrifying image of the demented albino in Maya’s gaze. As her madness descends into its final, crucial moments, Maya hurls Gautama to his death from the edge of the roof. From this juncture, the novel thrums with a cold, hysteric electricity.

As it reaches its conclusion, Anita Desai completes her successful creation of a world in which horrors of the flesh and tremors of the mind collapse into each other effortlessly.

Wives and husbands: marital disunion in Cry, the Peacock

“You go chattering like a monkey, and I am annoyed that I have been interrupted in my thinking,” Gautama tells a grieving Maya in the first chapter of the novel. This serves as the precursor to the dynamic of the couple throughout the narrative. Maya is always the emotional counterpart to Gautama’s rational sensibilities. The husband and wife live in two separate realms. Gautama’s is a private, intellectual world of transcendence and logical precision, whereas Maya is tethered to the earthly world – her plight is implicitly represented through the sustained metaphor of animals in anguish.

Desai’s domestic space is markedly post-colonial and neo-Indian. She belongs to a tradition of writers who have been liberated from the conservative constraints of colonial fiction in India. Such freedom enables Desai to flesh out the psycho-physical needs of her female protagonists. Maya is not only yearning for an emotional connection with Gautama but also sexual fulfilment. Maya is the domestic ‘other,’ seeking love and passion from Gautama, yet receiving instead reasoning and rambling philosophies. Maya’s desires are left unsatisfied, causing her to spiral into an existential predicament. Gautama is incapable of sharing her understanding of the real, living world. What the couple shares, then, is a covert sympathy for each other, left uncommunicated by both of them.

Within her splintered psychological self, facts of reality get transposed onto the eccentricities of her fancy. As Maya’s distress reaches its summit, the agonising wails of peacocks represent her state of helplessness: “Now that I understand their call, I wept for them, and wept for myself, knowing their words to be mine.” Inside the peripheries of her conjugal life, Maya herself is a snared creature. This is where Desai as a writer truly excels. The impact of significantly juxtaposing ideologies of the wife and the husband is executed masterfully till the very end. As she explores Maya’s worsening afflictions and repressions through the parallel sightline of Maya’s relationship with her father, psychoanalytic theories come into effect in Cry, the Peacock.

Cry, the Peacock as Indian Female Gothic fiction

Victorian Gothic literature is characterised primarily by its setting that elicits fearful sensations of impending doom. The plot essentially circuits supernatural hauntings, fateful murders or ancient curses. Placed at the very epicentre of the tale is the female body that is oppressed, possessed or haunted by tyrannical powers.

Ellen Moers in Literary Women: The Great Writers devised the term “Female Gothic” for the significant contribution of women writers to the gothic genre since the eighteenth century. The term has since evolved to embrace “a politically subversive genre articulating women’s dissatisfactions with patriarchal structures and offering a coded expression of their fears of entrapment within the domestic and the female body,” according to critics Diana Wallace and Andrew Smith.

A prominent trait of the Female Gothic is the staged victimisation of the woman. These heroines frequently pretend to be victims of the patriarchal system that dictates their actions, while simultaneously devising subtle ways to destabilise it. The insubordination of female characters through feigned weakness in gothic fiction has come to be known as Gothic Feminism. Gothic writing in India never emerged as an explicit stream of writing, yet elements of western gothic literature can be traced in many Indian novels. The primary difference lies in substituting classic Victorian elements such as castles, hauntings, and ancient apparatus with more potent representations of the terrors of caste, sexuality and religion. In the Indian context, dread is not evoked by external elements but rather emerges from within the familiar domestic space.

Anita Desai in Cry, the Peacock, does not operate beyond Maya’s house. Her heightening insanity steadily transforms the atmosphere of her home and by extension the novel, into one of inescapable dread. Dreams and visions that threaten the permanence of her marriage hum beneath the surface of every interaction between Maya and other characters. As plaguing memories worsen her psychological instability, the house becomes oppressive and disturbing on its own.

Maya’s alienation and fears of death are traditional elements of the gothic. At one instance, as Maya drifts off to sleep, her mind is unsettled by “a persistent sense of some disaster I had known, and forgotten, or perhaps never known, only at one time, feared and now rediscovered.” As the female protagonist navigates the unsettling domestic domain, the reader observes a woman displaced in a space entirely relegated to her by patriarchal authorities. From this angle, the story assumes feminist sensitivities.

Initially, Maya is shown as completely reliant on a saviour: “Am I gone insane? Father! Brother! Husband! Who is my saviour? I am in need of one.” As Maya’s hysteria reaches its climatic phases, however, she arrives at the realisation that “it might be Gautama’s life that was threatened.” It is when Maya accepts the inevitability of death, that she invites it into the familiar space of her home to kill Gautama. It is only after this merging of the familiar and the unfamiliar, the domestic and the sinister foreign, that Maya is able to claim her agency.

Cry, the Peacock is a brilliant testament to Anita Desai’s exploration of the female psyche, skillfully intertwining the gothic elements with profound psychological depth to craft a hauntingly evocative narrative.

About the author(s)

Gayathri S (she/her) is currently pursuing her master's in English. With a deep-rooted love for literature and writing, she hopes to streamline her interests towards a career in journalism. Alongside her studies, Gayathri has gained practical experience through internships in content writing, editing, and research. These opportunities have strengthened her commitment to impactful storytelling and managing projects aligned with broader social goals. Gayathri looks forward to merging her passion for writing with journalism, where she can explore and report on diverse narratives.