In the contemporary world, as countries move towards achieving gender equality, it becomes crucial to check whether the governance structures have narrowed the gender gap in property ownership or not. In agricultural economies like India, land becomes a critical subject. Where agriculture accounts for 19 per cent of its GDP, with about two-thirds of the population dependent on this sector, land in India is more than just a physical asset; it symbolises social status, livelihood, heritage, pride, and security.

In India, the culture of female land ownership is mainly based on inheritance, gifts, purchases, or government transfers.

In India, the culture of female land ownership is mainly based on inheritance, gifts, purchases, or government transfers. Here the government is the largest landowner and inheritance is the biggest mode of land transfer. That’s why, women’s ownership of agricultural land becomes a significant determinant of their economic and social status and the well-being of their families.

Data about female land ownership in India

According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), 31.7% of women and 43.9% of men own land alone or jointly, whereas only 8.3% of Indian women own land alone, and 13% own a house alone, 29% of women jointly own their homes and land. Whereas scheduled-caste (SC) and scheduled-tribe (ST) women’s land holdings are 19.7%, which is significantly higher than the national average of 12.9%, rural women hold 45.7% per cent more land than urban women.

The average size of women’s land holdings in India is 0.93 hectares, compared to 1.18 hectares for men and 1.15 hectares overall. Despite women constituting almost one-third of all cultivators, they own less than 10.34% of the land and operate only 12.8% of the holdings.

Societal exclusion of women from property ownership

Women in India have distanced themselves from property or land ownership due to patriarchal culture, where their roles are confined to caregiving, household work, loving their husbands, and taking care of children. Economic or social responsibilities are often assigned to male family members. In rural areas, agricultural land is mostly owned by men.

Women who do own land often acquire it through government schemes, reduced stamp duty, or as widows. Even then, their role in land affairs is typically limited to providing food to their husbands in the field or managing grain storage at home.

The 2015–16 National Family Health Survey and the Centre for Land Governance report highlighted wide disparities among Indian states in terms of female landholding.

The 2015–16 National Family Health Survey and the Centre for Land Governance report highlighted wide disparities among Indian states in terms of female landholding. Meghalaya had the highest landholding by women (26%), while Punjab had the least (0.8%). North-Eastern and Southern Indian states performed better in this regard. States with large agricultural populations, such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, ranked lowest. A report by Oxfam India, suggests that female land ownership, in the most populous states of India, like Uttar Pradesh is only 7.6%.

Legal framework for female land ownership in India

Laws on female land ownership in India vary across different religions and cultures. Hindu Women’s Right to Property Act, 1937, first provided Hindu widows the right to inherit their husband’s property. Hindu Succession Act (HSA) of 1956 and reforms among Christians, Muslims, and Parsis allowed Hindu widows to receive an equal share of their intestate husband’s property as their sons in a joint family.

Hindu Succession Amendment Act (HSAA) of 2005 further reformed these laws by abrogating the survivorship rule and recognising daughters as legal coparceners, giving them equal inheritance rights. Land Acquisition (Right to Fair Rehabilitation and Resettlement) Act, 2013, recognised widows, divorcees, and deserted women as separate families, advancing the cause of women’s land rights. Some of the court cases such as Prakash v. Phulavati (2016), Danamma v. Amar Singh (2018), and Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma (2020) clarified and reinforced the equal inheritance rights of daughters, eliminating the requirement for the father to be alive on the date of enforcement of HSAA 2005.

Women’s perceptions and the misuse of ownership

When discussing land management with female landowners in the author’s hometown in a rural village of Uttar Pradesh, many women told FII that, they feel it is unnecessary to manage their property, believing their husbands and sons can take care of it. As a result, the names of female landowners are often misused by family members to avail benefits of certain government schemes.

Patriarchs of the family frequently register land in the names of their wives, daughters, and mothers to benefit from special provisions, such as lower stamp duty on female property registration. Additionally, they use these women’s records of rights to obtain loans from banks at lower interest rates for setting up businesses.

This misuse reflects a complex interplay of cultural norms, exploitation of legal loopholes, lack of awareness, literacy and economic realities that affect women’s access to and control over property and land.

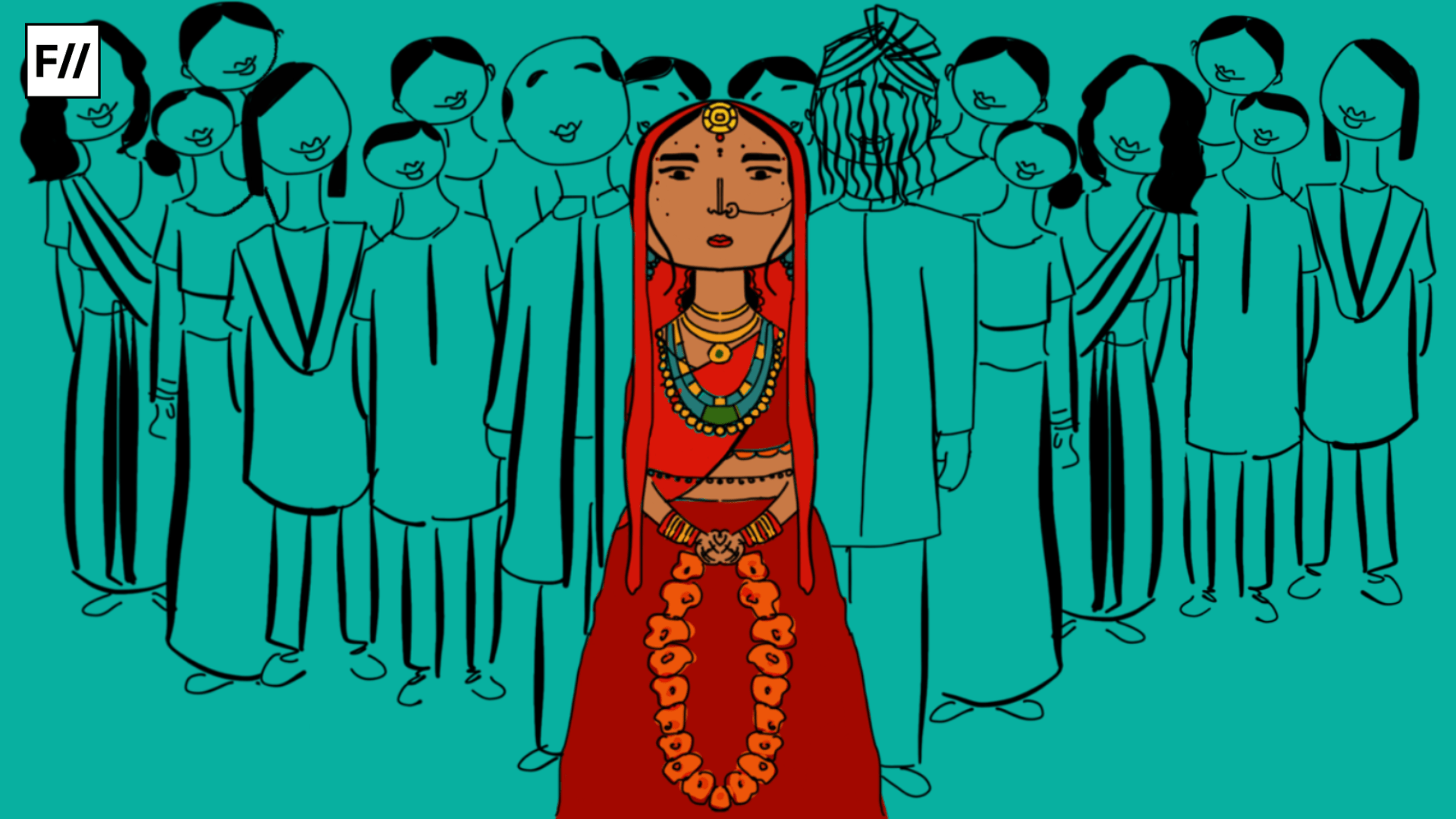

In many societies, including rural India, women who assert their rights to inherit property are often seen as family breakers or bad daughters. In some households, it is believed that women take their share of wealth from their maternal side in the form of dowry, and therefore, they do not deserve a share of the property. This belief is reinforced by the notion that fathers and brothers spend their hard-earned money on their daughter’s marriage to secure their future. Their share is already paid off in the form of dowry.

Replacing dowry with property rights

Deeply ingrained cultural norms of dowry can be transformed into an opportunity for women’s empowerment, by replacing a culture of dowry with the transfer of property rights in marriage so that women can gain tangible assets that provide them, with a sense of self-confidence, give a source of income, belongingness, identity and ownership.

This will help in reducing women’s dependency on their in-laws and husbands, and also reduce the control of family on the individual.

This will help in reducing women’s dependency on their in-laws and husbands, and also reduce the control of family on the individual. Where for many of India’s women, ownership and control over economic assets, especially property and land, remains a distant dream, this approach will ensure that women have a secure stake in their family’s wealth, promoting their economic independence and social status.

Government and civil society organisations should advocate for this idea to be widely accepted and implemented. They can help in educating family members about the benefits of replacing dowry with property rights via companions and movements. It can also help in dealing with social evils, for example, Bina Agarwal, Professor of Development Economics and Environment at the University of Manchester, stated that ‘for women owning even a small plot of land can greatly reduce the risk of poverty, especially in case of widowhood or divorce and reduce the risk of domestic violence’.

In the current scenario, organisations like EPW has highlighted the issue that NFHS data does not provide precise insights into the extent of female land ownership in India. The lack of accurate statistics on women’s land holdings raises concerns about the country’s ability to address poverty alleviation effectively. With only 13.9% of agricultural land owned by women nationwide, the cultural barriers to female land inheritance appear daunting, making land ownership seem like an unattainable aspiration for many women. This situation showcases, the flaws in the land governance system, including inadequate awareness, poor infrastructure accessibility, and the rigidity and insensitivity of laws towards female landowners.