Gastronomy has always been gendered. The appetite of the woman, in the entirety of its meaning, is something that the patriarchal world order has always striven to control and keep in check. The purpose has always been to ensure that the woman does not take up space and, in turn, makes more space for the man.

Women’s appetite, bodies, and desires are all interrelated, and subsequently their appetite, encompassing hunger, needs, and pleasure, is encouraged by the patriarchal law to be repressed and controlled. Such is the politics of the platter, visible in every aspect of the platter: from the quantity of the serving to the kind of food one eats, to the time of eating, and finally the gendered notion of ‘fasting,’ or not eating. It is this politics of platter that extends beyond the platter and points at the larger constructs of our society.

The mathematics and quantification of appetite

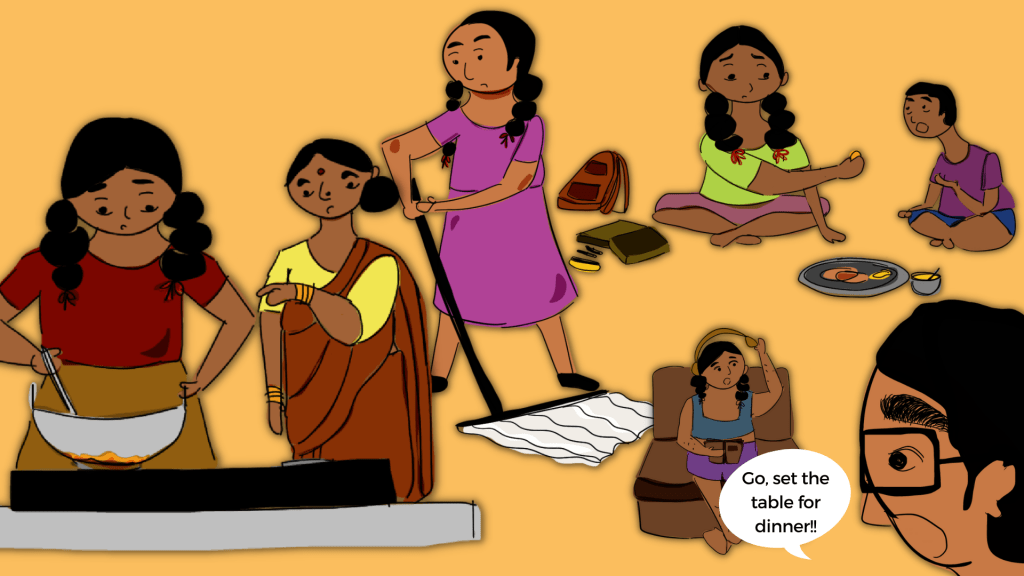

Young girls are taught to control their appetites and hunger right from childhood as an initiation into their gender performance as a woman. On the other hand, young boys are generally more encouraged and tend to have greater appetites from early on. This is observed in both portion sizes and consciousness at calorie intakes, where women tend to be more calorie conscious and hyperaware of the numbers on the food that they are consuming.

So while boys and men are said to have ‘hearty appetites,’ when a girl tries trudging along the same lines, her behaviour is labelled ‘unfeminine.’ This is something that the girl also internalises from her observation of the society around her: whether it is her mother as the womanly ideal who follows these diets and is burdened by the weight of the same harmful ideas, or the glamorous portrayals of women in media, which too is centred around the male gaze. And now the hyper-presence of social media as well that continues to perpetuate and impose these impossible ideals of femininity.

To quote some lines from Caroline Knapp’s ‘Appetites: Why Women Want,’ which perfectly describes this common experience of womanhood: At the very least, the gospel of femininity, which is essentially self-negating, may explain why quality of guilt and murkiness can so easily leak into a woman’s experience of appetite, a profound uncertainty about entitlement, or even a sense that desire itself is indefinable or inappropriate. A woman in her mid-thirties, whose mother was a “paragon of self-sacrifice,” a woman who lived for her kids, who always took the smallest piece of meat on the platter and the most bruised piece of fruit, tells me she has struggled her whole life to believe that her own desires have any weight at all.

Another, thirty-eight, talks about inheriting from the females in her family a certain “blankness about desire,” as though that entire territory were simply off limits, shrouded in a fog. “The needs of men were always loud and clear,” she says. “My father needed dinner at seven o’clock and got dinner at seven o’clock; my brothers needed the car for football practice and got the car for football practice. But my mother and my aunts—there was this feeling that it would be unbelievably selfish to let your own needs eclipse someone else’s, so you didn’t even think about it.”

The internalisation of this control over diet ends up creating what American philosopher Susan Bordo calls the reproduction of “docile bodies” in the service of gender normalisation. What this means is that after a certain point, there is no need for external interference to control the diet of the woman. It becomes something that she starts internalising and following by herself, thereby perpetuating these toxic gender codes.

This outright call to restrain the appetite of the woman is also the most visible manifestation of restraining her sexuality. While the sexuality of the man is unapologetically unrestrained and given the central stage like his appetite, the woman’s sexuality is a ‘taboo’, something that must be ‘hushed,’ and never given a vocabulary. She must ‘serve,’ the man in both contexts, and her own appetite and needs are secondary. Following the same vocabulary of food, it is acceptable for a man to have a ‘hearty appetite,’ an outspoken sexuality, while the same cannot be said of a woman.

The gendering of food items

Gender does not remain confined to living beings but also seeps into food items. One may wonder: since when did food items have a gender? The Scroll found that ever since the late 19th century, Americans started attributing gender codes to food items, and subsequently, by the 20th century, magazines and newspaper columns started pushing forth the concept of ‘the lady’s lunches,’ food that is ‘dainty.’ This includes decorative food items that are very light and unfulfilling, like salads with fanciful dressings, which to date carry that gendered connotation. And the ‘man’s meal,’ of course consists of meat, spices, and other filling dishes. As always, the American Dream is sold and marketed to the entire world as this pursuit of perfection, and so this idea spread to other countries alongside the beauty standards of glamorous Hollywood.

Interestingly, in these cultural contexts, healthier food has always been marketed as feminine, and unhealthy, ‘adventurous,’ food has been marketed as masculine. This again goes back to the gendered idea of appetite that we had explored above, where women are discouraged to indulge in satisfying their food cravings and be conscious of their calorie intakes, while men can indulge freely in eating whatever they want.

There is another gendered angle to food, the metaphor of women as desserts and sweets carrying with it connotations of sexualisation and objectification of women, which also trails down to unrealistic expectations from women’s genitals and bodies.

In our own context as well, the language attributed to food items carries gendered connotations across the various Indian languages too. The grammatical rules of the Indo-Aryan family of languages follow the idea of assigning gender to inanimate objects, but there are some interesting observations made in a study. A cheaper sweet like jalebi is ascribed feminine attributes, while a similar but more expensive sweet ghevar is considered regal in Rajasthan and given a masculine attribute. The thinner dishes in texture tend to carry feminine connotations, like dahi, papadi, and basundi, while the thicker and richer ones, like chaach, fafda, and shrikhand, carry masculine connotations. The same paper points out how some communities distribute jalebi on the birth of a daughter, but peda, which is a relatively fine milk-based sweet, on the birth of a son.

And not to forget, attributing feminine codes to alcoholic items like madira, sharaab, and daaru, which carry a sensual and romantic connotation too.

To eat or to not eat

It’s frequently observed that women in most societies eat the last and eat the least after serving everyone and ensuring everyone has eaten. They are also the ones cleaning the leftovers and eating the lower-quality food at the end. There comes also the gendered idea behind fasting, we may claim nowadays that it’s a voluntary practice, but historically across traditions, the idea behind fasting has always been about the self-sacrifice of the woman. The deep-rooted gendered and patriarchal ideas behind various traditions and cultures are hard to completely rid off.

In the Indian context with reference to Brahmanical ideas and rituals, it is the woman of the family who indulges in fasting to get an ideal husband, then for the health and well-being of the husband, or for the entire family, and even for wealth and success.

During Ramadan, the gendered idea of fasting is not present, however, the fasting women of the family are expected to prepare lavish meals every day. Aaliya Bukhary, a writer and a student from Mumbai says, ‘I think the most heartbreaking instance I have witnessed is during festivities, such as Eid: women do not partake in the celebration of eating together with the entire family at the dinner table. They’re supposed to help each other cook, and the festival and celebration become something primarily for the male members of the family to enjoy. Even when the women in the family are unwell, they are expected to cook for the family. Essentially, there are no exceptions.’

American philosopher Susan Bordo makes an observation regarding western religions and the concept of self-control.“Throughout dominant Western religious and philosophical tradition, the ‘virile’ capacity for self-management is decisively coded as male. By contrast, all those bodily spontaneities—hunger, sexuality, the emotions—seen as needful of containment and control have been culturally constructed and coded as female.” There is also the Victorian phenomenon of the ‘fasting girl,’ where women and young girls fasted themselves to the brink of death in the attainment of an unattainable spiritual ideal.

The takeaways from gendered politics of platter

The politics of the platter has historically been there, and it continues to be perpetuated. In every new generation, the same harmful ideas behind women and their relationship food keep getting repackaged and keep making a comeback. Young girls and women throughout the years continue having a distorted relationship with food due to a myriad of reasons, all of which can be traced back to the internalisation of the patriarchal law that forbids them to take up space and challenge its underpinnings.

By observing the ‘simple,’ act of eating food, a plenitude of far-reaching implications reveal themselves. As women, we may be aware of the harmful systems behind all of these ideas and their even more harmful impacts on our self and body, and yet if only it were that easy to rid ourselves of these chains binding us.

About the author(s)

Sarah (She/Her) is your local student journalist and writer pursuing her Bachelor's in Literature from Delhi University. She seeks to strike a balance between a chaotic chronically online gen-z and an insatiable learner. At the risk of coming across as cheesy, she quotes Oscar Wilde on being asked to introduce herself, "To define is to limit."

Change your web name from Feminism in India to Misandry in India. 🥰

That’s why the obesity rate in women in India is much higher than that of men? Men must at fault for these higher obesity rates in women, right?