Sneaking an egg to make an omelette and panicking about the smell going outside, even after having a space for yourself in your late twenties, is pathetic. I never had a space of my own until recently. It’s been six months since I have been living in a rented home. The owners first demanded that I do not cook non-vegetarian food in the kitchen. It was an ‘Agrahara,’ where Brahmins lived. After a relentless search for an affordable space to stay, I had no other option but to stay. I have fantasised about living alone almost all my life. Cooking for myself the way I like and feeding the people I love was always a dream.

As a person who comes from a coastal area, my diet has always been enriched with seafood. What I eat has always been a part of who I am; it is my identity. I had to make compromises with my identity when I chose that space, even though I had no other choices left. But it’s been a long time since this battle of identity began.

I was in the 5th standard at that time. In my memory, that is the first time I have been discriminated against by caste in the name of food. Maybe this caste discrimination had happened before, but it was not strong enough to sustain in a 10-year-old memory. I studied in a Government LP school until my 4th standard, where we used to have lunch from the school and sometimes bring it from home. Every one of us sat together to have lunch and share each other’s food.

One of our teachers asked the class one day, “Who all eat the dead, stand up.” He meant those who consume non-vegetarian food. And then he started a lecture on why eating non-vegetarian food was a crime. He said, “If you visit a jail, most of the criminals would be Muslims and those who eat non-veg food. You can’t even see a single Brahmin as a criminal. Eating meat makes people criminals.” For the first time in life, we felt like we were criminals.

From 5th to 12th, I studied in a government-aided school administered by a Brahmin management. Almost all teachers were Brahmins. But as it was the only government school in that area, many people from the marginalised and minority community sent their children to that school.

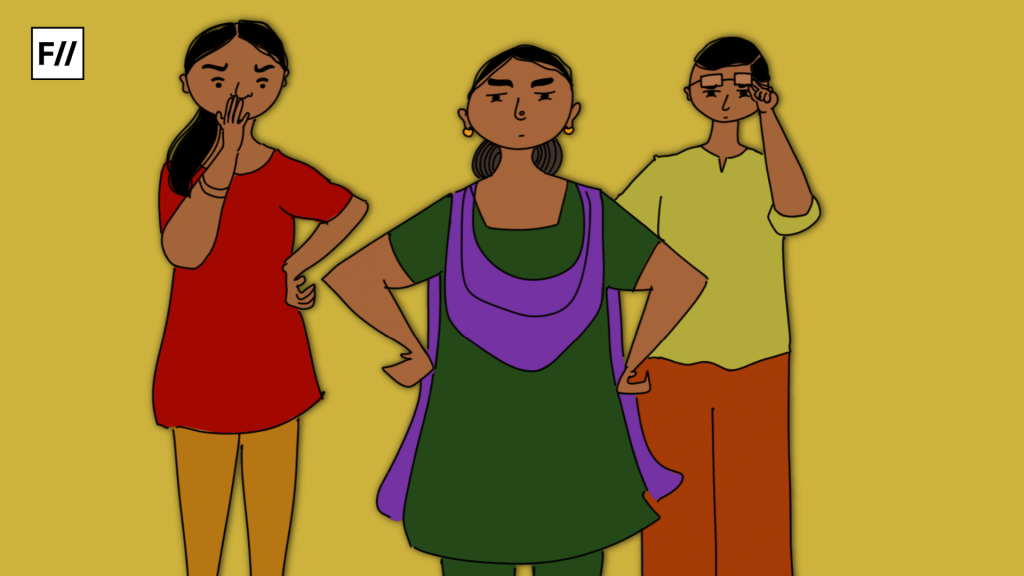

We were having lunch together at the new school, and I shared the curry I brought with the girl sitting next to me. She immediately got angry and shouted at me to take it back from her plate. I was embarrassed and ashamed in front of my classmates. She was a Brahmin girl. I didn’t know it was caste that made her shout and not even touch my food. That was just the beginning of what was ahead.

One of our teachers asked the class one day, “Who all eat the dead, stand up.” He meant those who consume non-vegetarian food. And then he started a lecture on why eating non-vegetarian food was a crime. He said, “If you visit a jail, most of the criminals would be Muslims and those who eat non-veg food. You can’t even see a single Brahmin as a criminal. Eating meat makes people criminals.” For the first time in life, we felt like we were criminals.

When I was in high school, one day the school dispersed early, and I went to a friend’s home. She asked us, “Namukk choru ‘THINNAM’?” (Let’s have lunch?) Immediately, her aunt said, “Don’t say choru ‘thinnam,’ like choka piller” (choka piller means – children who belong to a lower caste, ‘Ezhava’ – upper caste people call them ‘chokan’ ‘chovar’ etc). You should say ‘Namukku oonu, kazhikkam.’ I belonged to that community, and the meal I had from there felt like a thorn swallowed. Both of the sentences have the same meaning, but that was when I realised caste didn’t just dissolve in the food we eat, but also in the language, slang, and in fact in our whole identity. My friend’s aunt reminded me that my friend and I are different even though we are sharing lunch. These differences have accompanied me forever.

Recently, IIT Bombay sanctioned segregated spaces in the hostel mess for people eating ‘Pure vegetarian food,’ in the name of inclusivity, amidst several caste discriminatory allegations that were raised against this elite educational institute but were not addressed. This practice of prioritising a vegetarian diet in the messes is a common thing in elite educational institutions as if it is a norm. There are hostel messes which only provide vegetarian options, then there is no matter of inclusivity. As these spaces are predominantly occupied by people from the upper strata of society, the rest of the people have to follow what they are following.

I decided to become a vegetarian when I was in 10th. I came to that decision after reading a book by a famous poet, Sugathakumari, in Malayalam. She was an environmental activist too. In her book, she mentioned the cruelty of slaughtering animals for food. I decided to give up my favourite food to become more ‘environmentally conscious.’ I was a vegetarian for the next four years. As we lived in a coastal area, fish was the common thing in our everyday diet at home. It became an extra effort to make a vegetarian alternative as food only for me. But when I look back on it, I got more acceptance from the savarnas but never equal to them.

One day I asked my friend, who was a Brahmin and who wouldn’t eat onion and garlic as they consider it as ‘impure,’ like meat, “Why don’t you eat non-veg, is it because you love animals?” She said, “No, I don’t like animals.” Later I started thinking, where does this purity lie? Even though I became a vegetarian, I could never become a ‘Pure vegetarian,’ as I was impure by my birth itself. I went back to my roots as neither my taste buds nor my identity was ever accustomed to the changes in my diet, even after four years of following it.

As the Brahmins claim, are the Brahmins really ‘pure,’ vegetarians? Dr B.R Ambedkar in his book, “The Untouchables, Who Were They? And Why They Became Untouchables,” shows how in the Vedas and the sacred scriptures of Brahmins, it is written about Brahmins having non-vegetarian food. Brahmins became vegetarians and gave up eating non-vegetarian food, especially beef, to regain their power position in society which was replaced by Buddhism as it gained popularity and wide acceptance. Buddhism was the religion of the masses, and they criticised Brahmins for animal sacrifices. So, the Brahmins decided to give up the ritual of animal sacrifice and proclaimed cows as sacred animals. In this way, those who eat cows become untouchables. Brahmins never became vegetarians for the love of animals. It was mere power that made them give up this.

Recently, a film named ‘Annapoorni,’ was deleted from Netflix because a Muslim character cites in ‘Valmiki Ramayana,’ that Rama eats meat. It made an outrageous reaction among the Hindu right-wing group as the protagonist of the film was a Brahmin woman who pursued her dream to become a chef and found it difficult because she had to cook meat. What was the matter of provoking, was it the Muslim character who cited verses from Valmiki Ramayana stating Lord Rama used to eat meat? The film was withdrawn from the platform and the entire crew of the film had to make an apology to the Brahmin community. But, in the Valmiki Ramayana, there are instances in which Rama eats meat and Sita is fond of deer meat. Even though the followers want to believe the contrary.

I learned about the term ‘Sanskritisation,’ during my graduation, where the people from lower castes tend to adopt the lifestyle and dietary practice of Brahmins to attain their social position. This social position of twice-borns is not achievable to the lower caste people even if they are financially stable. When we talk about reservation and representation, savarnas whine that people who get reservations are looting the government’s money. Reservation is not meant to be a poverty alleviation program. It is to ensure appropriate representation. Even though savarnas are a minority, most of the important positions in society are occupied by them.

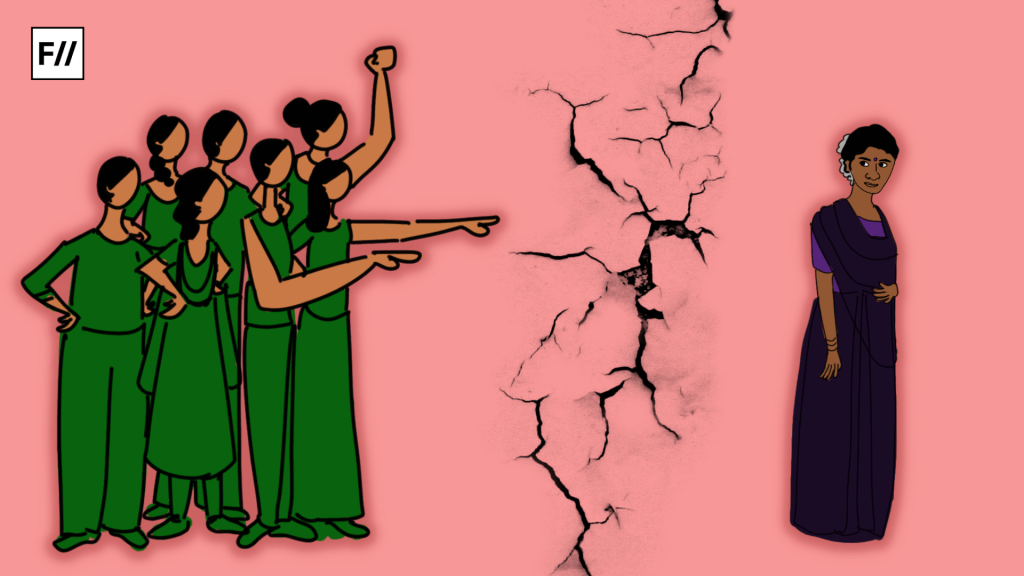

It took me some more years to learn the politics of what we eat. When people are being lynched to death in the name of their food, when the elite academic spaces in the country ban non-vegetarians in the mess, when my liberal and progressive savarna friends say, “No, we don’t cook beef in our kitchen,” or “Do you eat dried fish? I gag at the smell of it,” or “Do you eat everything that doesn’t bite, or do you bite them back?”

Even the people who propagate veganism in India are the subtle warriors of casteism. Any ‘ism,’ that makes you look down upon people over their culture, lifestyle, and food is not humanitarian. And where is the empathy of the people who only eat plants and plant-based food when people get killed in the streets because of the food they eat, because of their religion and identity? Representatives of people in parliament are not bothered about the hike in the price of onion and garlic, as they won’t eat them. All these advocacies are to keep the power vested only in the hands of savarnas so that they can exert this power on ‘impure‘ people.

In a country where the percentage of people who can’t even afford a meal for a day is very high and people die of nutritional deficiency, ethnic, Indigenous, minority, and lower caste people are looked down upon for what they eat. Those who eat the dead and those who get killed due to it don’t even make it to the headlines these days.