Trigger Warning: suicide

What does it mean to exist in a society that places the utmost importance on the individual? Lau Yee-Wa’s Tongueless explores the pitfalls of the individualistic society that has engulfed the world, in the backdrop of the Mandarin imposition on Hong Kong. Tongueless or Sat Jyu is a breathless novel, written by Lau Yee-Wa and translated from the original by Jennifer Feeley, and it forces us to ask the question: how far are we going to go in the name of individuality?

The plot of Tongueless

Tongueless is the story of two rival Chinese Language teachers at a Hong Kong high school–Ling, and Wai, both struggling with the imposition of Mandarin on the Cantonese-speaking populace of Hong Kong. Hong Kong has always remained a hotbed of controversy since the British released it to the Chinese, who have since then set out to destroy every aspect of independent Hong Kong life and autonomy.

Tongueless or Sat Jyu is a breathless novel, written by Lau Yee-Wa and translated from the original by Jennifer Feeley, and it forces us to ask the question: how far are we going to go in the name of individuality?

The gradual imposition of Mandarin onto the Cantonese speakers of Hong Kong is also a deliberate attempt to undermine the autonomy and sovereign authority of Hong Kong, as well as a sign of disrespect towards a population that, even as recent as 2021, had 88% of its people speak Cantonese.

Tongueless opens after the death of Wai, Ling’s rival teacher, who had killed herself in a manner too gory to describe on paper, haunts Ling and her mind. Ling, who had always been someone who preferred to rise through the ranks by maintaining good relationships with everyone around her, especially those in higher positions, finds herself thinking about the death of Wai more often than not, wondering why the department had taken it upon themselves to ignore the phenomenon of Wai’s gruesome death.

She is haunted by it, despite wanting to conform and ignore the death of Wai as the rest of her colleagues, but ‘Ever since Wai died, she rarely got a good night’s sleep. Gazing at the orange light halo projected on the ceiling from outside the window, she recalled the thick ripples that spattered when Wai collapsed into the pool of blood. Even when she was sleeping, the rumble of the electric drill just before Wai died still echoed in her ears, startling her awake. Wai clearly killed herself. She was her, I am me – what do I have to do with any of it?‘ Ling’s own conscience refuses to allow her to look away from Wai’s death, as subconsciously, she is also aware that Wai’s fate could very well be her own.

Ling’s own conscience refuses to allow her to look away from Wai’s death, as subconsciously, she is also aware that Wai’s fate could very well be her own.

Wai appears as a disturbance in Ling’s life. Wai is a new teacher, whose enthusiasm for teaching is only rivaled by her enthusiasm to learn Mandarin, a habit that marks her as “weird” among the teachers. Ling remarks in Tongueless, ‘Wai was too weird, always wanting to finish grading homework the fastest and work the hardest, and, even when it came to making friends, she had to be ‘the best’. In the end, however, she achieved none of the three. Wai wasn’t like a typical Hong Konger, who, after spending a little time out in the real world, wouldn’t be as rigid and stubborn as her. Wai was more like the new immigrants in the school, dumb and isolated from the world, not caring about the jokes that Hong Kong students told or the pop culture they liked, thinking that doing their best was enough.‘

Wai imagines that doing her best, and trying her hardest to learn Mandarin, would be enough to help her acceptability in a society that places no value on the collective, and instead on the individual. Ling views Wai as a threat because of the highly individualistic Hon Kong society that does not allow her to view Wai as a compatriot, merely a competitor. Wai, by contrast, being a much younger teacher, views Ling not as competition, but as someone who is on the receiving end of the same kind of gendered and sexual discrimination as her,

‘Whether studying English or Mandarin, Hong Kong people are always in a female… no, I mean an in – yes, an infer-ior po-position. We have no opportunities to listen or speak, so we always study… it’s not good. If possible, I’d like to create a Mandarin-speaking en-fry – no, en-vi-ron-ment. This is the only way to speak as well as those whose mother tongue is Mandarin.’ this attitude of hers is something that can only be achieved through the endless optimism that comes with youth, and Ling, the more jaded of the two, understands this instinctively, but also remarks that Wai was an uncommon persona, even in the known parlance of the Hong Kong school where Ling had worked all her life in Tongueless.

In Tongueless, when Wai fails the LPAT, ‘the Language Proficiency Assessment for Teachers, used by the Education Bureau to assess Chinese language teachers’ ability to teach in Mandarin.‘ she turns inward to express her grievances and frustrations, descending into depression and self-hatred, where she continually thinks she has no talent for languages. When Wai dies by suicide on camera, she is gripped with a singular desire, that to change her brain.

When Wai dies by suicide on camera, she is gripped with a singular desire, that to change her brain.

One can argue the drill is simply a means to an end, Wai’s goal was not death either. It was simply to change her own mind, to rewire it into something that grasped languages better. She says as much in her final address, ‘I was born too stupid. I need to change my brain.’ Ling being affected by Wai’s death is her acknowledgment that the individualistic society of Hong Kong has broken her down, to a point where it has become increasingly difficult for Ling to return to her normal lifestyle after Wai’s death.

Individualism and language

Language is spoken individually. By virtue of its existence, Language is both social and individual, making it a complicated sociopolitical being. Language has historically been used as a tool to oppress as much as it has been used as a tool to enrich. The 1997 handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to China (on the provisional agreement that it would be allowed to maintain its autonomy), has brought about many changes, especially in the imposition of Mandarin Chinese on a population of largely Cantonese-speaking people.

If we look back on our own nation, we might find some similarities with the imposition of Hindi as a national language, and especially as an official language in communities that have historically spoken regional dialects, not mainstream Hindi. The imposition of Hindi on Marathi speakers and Bengali speakers remains a point of contention, as language is also one of the most powerful tools of nation-building and fomenting nationalistic spirit. To destroy a community’s language is to also destroy the centuries of literature that they have, oral and written narratives. To impose Mandarin Chinese on a population that is one of the only sizable Cantonese-speaking city-state is nothing short of destroying the moral and psychological backbone of a nation that continues to struggle under Chinese rule.

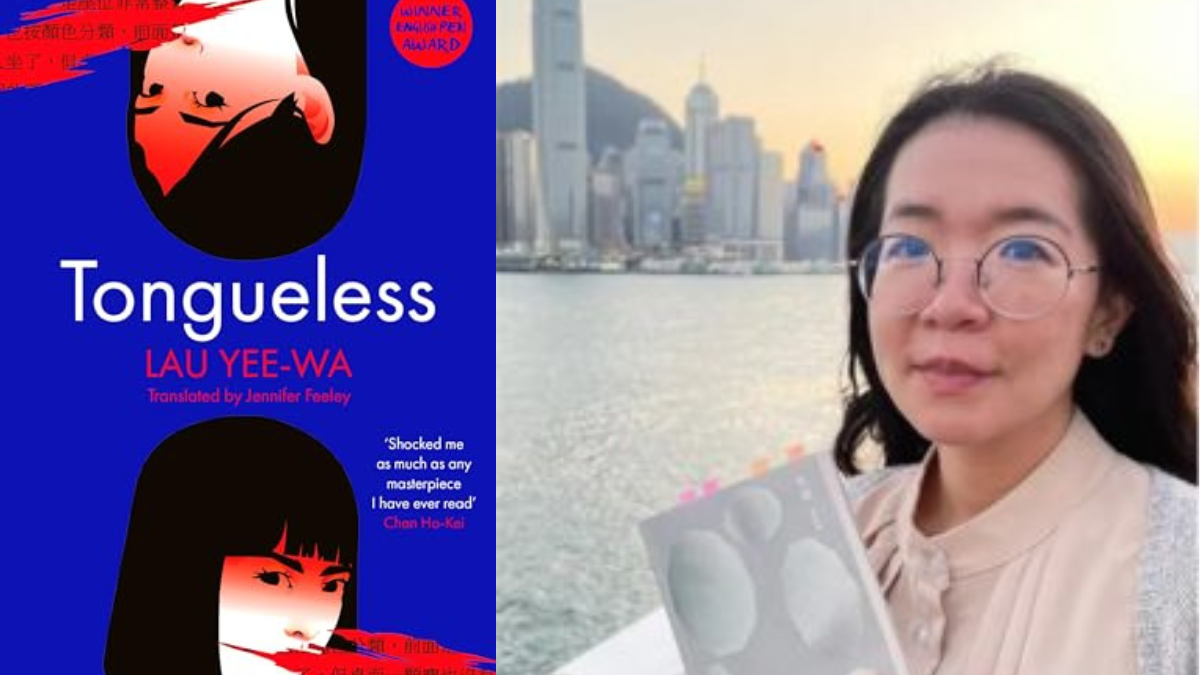

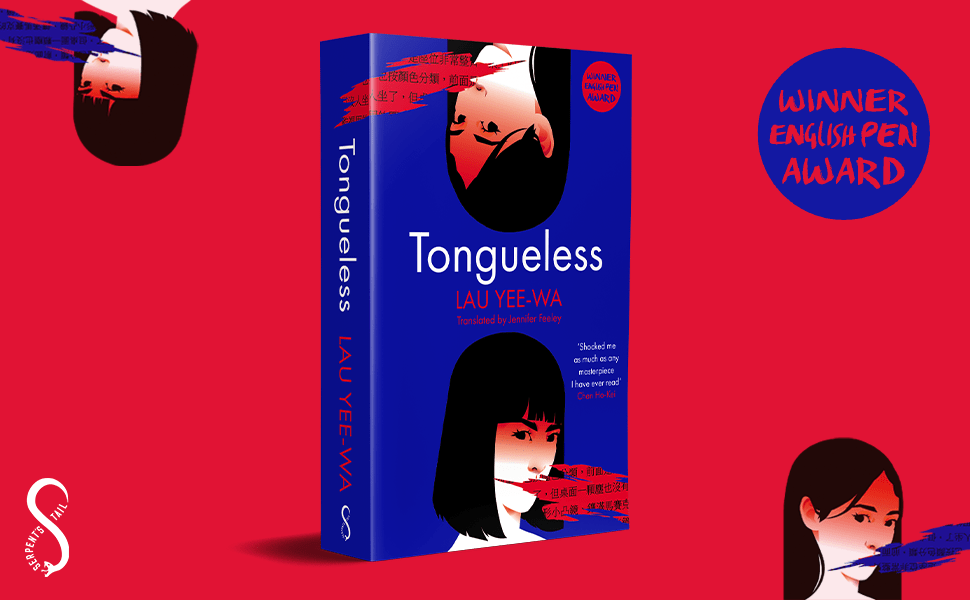

The cover of Tongueless features Wai and Ling, acting as mirrors of each other. Perhaps this is the moral, if such a thing exists, of Tongueless, where the individual is reflected in the public, and the public in the individual. Jennifer Feeley’s excellent translation mesmerises at every step, and overall, Tongueless is a great read about women, capitalism, and individualistic, oppressive society.