Urvashi Butalia’s ‘The Other Side of Silence: Voices From the Partition of India,’ is an account of the many personal narratives that have often been invisiblised in the broad ‘history,’ of the partition of India. Anecdotes of real people and real stories have often been lost amidst the ‘facts,’ and ‘numbers,’ of the partition. These stories are a perspective on how the people, who essentially make up history, have perceived these ‘facts.’

Butalia combines her primary source interview accounts with various kinds of secondary information: official documentation and unofficial accounts of diaries, memoirs, letters, etc. to present a comprehensive take on the history of the Partition.

As she makes it clear from the outset, her work does run into some obstacles, like the scale being limited to the partition of Punjab, the lack of resources from Pakistan, and most importantly, trying to work with memories of people and articulate the inarticulable. Above all, Butalia seeks to read into the silences of the marginalised: women, children, Dalits, and other oppressed communities who have been denied a voice in the discourses surrounding the history of the Partition of India.

Blood: The Butalia family chronicle of partition

Urvashi Butalia begins her task by chronicling the story of her own family, her own uncle Ranamama, who decided to stay back in Lahore when the family moved to India and also held back his mother. Butalia’s mother lost contact with both her brother and mother, and as a result, partition divided the family by sowing the seeds of grudges.

But after coming to Lahore to speak to Ranamama, Butalia felt an odd sense of familiarity and comfort in his presence. Ranamama was connecting to his kin after 40 years of radioactive silence, and through their conversations, Butalia and the readers both realised the extent of sorrow and pain that he had to go through after he chose to stay behind. Ranamama converted to Islam to sustain himself in Pakistan, but the alienation and dissociation that subsequently followed this decision is something that haunted him every day ever since. Ranamama ended up not having any place to call ‘home,’ and no true ‘family.’ But this project undertaken by Butalia ended up reconnecting the family, first through letters and then a teary reunion in Lahore.

Butalia traced the roots and found the seeds of partition as not sprouting from the religious debates between national leaders but from the socio-economic differences on the ground that have existed for long between the Muslims on the one hand and the Hindus-Sikhs on the other.

Despite this, Butalia’s mother still could never forgive her brother for one significant thing—taking their aged mother from her. Butalia chose to also show the other side of Ranamama’s story with the story of her mother and grandmother. Her mother Subhadra Butalia’s story was the tale of a woman who travelled amidst the partition all by herself, having no place to go and grappling with feelings of loneliness and betrayal by her brother. Meanwhile, her grandmother Dayawanti in her old age had to deal with the separation from her children and the sense of alienation that came from conversion to Islam.

‘Facts’: the humanity behind numbers

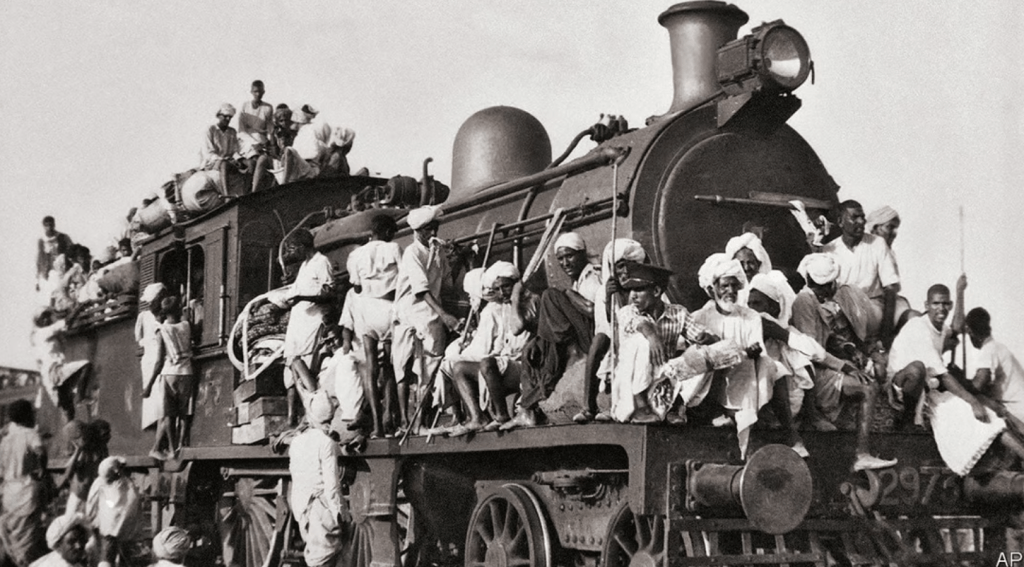

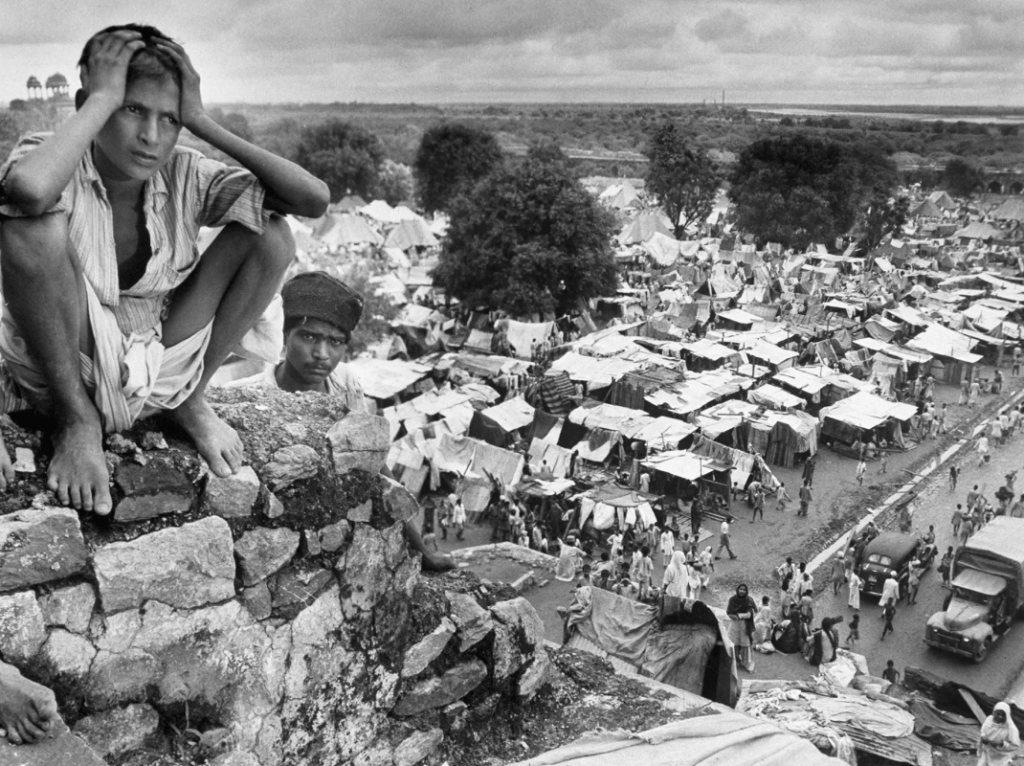

In this segment, Butalia explored the widely known ‘facts,’ of the partition—information that was readily available for the public and known by all of us. But what most of us may be guilty of unconsciously doing is forgetting the real human beings and real stories that form these ‘facts,’ which is what Butalia reminds us about in this section by trying to articulate the inarticulable trauma and feelings that lie hidden behind these ‘facts.’ As Butalia puts it, the solution of ‘Partition,’ actually became the beginning of the problem.

The common people grappled with the anxieties of lack of transparency and information regarding the exact meaning and implications of the partition. In their frenzy, none could anticipate the scale of the unprecedented violence and the sheer numbers of people who would migrate to the other side. In this same frenzy, common people like Harjit and Nasir Hussain, who were ruthlessly killed in the anonymity of the partition violence, are now living, haunted by the ghosts of their past. Butalia explored the contradictions and flawed logic behind the partition plan and the herculean responsibility borne by Cyril Radcliffe, who had to draw the boundaries and permanently alter the lives of millions.

Butalia traced the roots and found the seeds of partition as not sprouting from the religious debates between national leaders but from the socio-economic differences on the ground that have existed for long between the Muslims on the one hand and the Hindus-Sikhs on the other.

Women: the silenced and erased

This section of the book on the stories of the women during the Partition sought to give voice and read into the largely prevailing silences of the women on their accounts of the Partition, women who had been erased, silenced, pushed to the margins, and never given the space to speak. Butalia introduced us to the stories of some real women behind these numbers of thousands across the borders who were raped, subjected to violence, humiliation, abduction, forcible conversions, and marriages, and overall a series of life-altering events and traumas that language shall always fail to articulate.

In this segment, Damyanti Sahgal’s story is a particularly significant account not simply because she played a major role in the Indian state’s rescue operations for the abducted and abused women stuck in Pakistan, but also because it tells the story of how the Partition rendered the women completely abandoned and ruptured the normal course of their life. Damyanti’s conversations with her sister Kamla were able to give us an insight into how desolate the survivor woman had truly been and how she had been simply “forgotten,” by her kin. She, like many other women survivors, had been fighting a lonely battle ever since the partition.

Butalia showed how many of these women had been erased by their families, who refused to mention the rapes and abductions that occurred in their family history during the Partition. It was the hidden histories of these forgotten, erased, and silenced women that Butalia had tried to unearth.

‘Honour’: death over tainting the purity of community

Butalia presents many problems with the rationale and execution behind the ‘recovery,’ operations that both the states of India and Pakistan were performing. The question of honour became a key driver of the discourse on the questions of women during the partition. On the Indian side, the question of Hindu and Sikh women overlapped with the image of Bharat Mata, the pious ideal woman whose honour must be protected.

Pakistan, along with Muslim men, became a signifier of the attack on the dignity of the Hindu women and Mother India at large. It became a question of life or death for the Hindu men to restore the honour of the mother and bring back the Hindu women even if they may have been ‘polluted.’ As Butalia points out, partition then became a violation of the mother and her body, and the recovery operation became a national project to restore the honour of the state.

In this entire mainstream nationalist discourse, the woman was denied her personhood and her say on the matter of her safety and recovery. ‘Recovery,’ did not concern itself with the interests of the women but with the question of national honour.

In the name of honour, people like Mangal Singh killed, or in their words, ‘martyred,’ their own family of seventeen women and girls, all for the ‘ultimate threat,’ that was being caught by the Muslims and to save the ‘purity,’ of their religion and honour. Rajput women revived the tradition of self-immolation, and some like Basant Kaur had survived the mass-suicide attempt because the well they jumped into was too full.

This mass suicide and honour killing of women was another kind of unprecedented violence taking place, never mentioned in mainstream discourse and rather always recounted with the tone of heroism and valour of the ‘upright,’ women.

Children: the act of existence is contentious

Partition records hold no accounts of children as if they had been erased altogether from history. And yet every other family had lost a child—or rather, the child had been left behind and abandoned. Children too became primary victims of honour killing alongside women, and some, like Trilok Singh, who managed to bargain for their lives with their families, remained scarred for their lives.

The trauma of partition as children was something that was inexpressible through language and altered their lives so deeply that it made it hard for the survivors to live with relatives even years after it was over. Such was the case of Kulwant Singh, a man who survived the mass suicide attempt by the womenfolk of his family, but his hands were cut and his legs were burned. He, like many others, continues to have nightmares of the time.

Others like Murad can only recount the fear they felt as a child since they managed to survive on their own after losing all their family and being left with no food, money, or place to go. There were also others, like a female doctor, who chose to suppress her past and remain deliberately silent while distancing herself from the identity of an ‘ashram child,’ owing to her socio-economic status and identifying instead as a self-made woman.

In rescue operations, there were many hurdles in the ownership of children as well, since some were born of sexual violence, illegitimate marriages, or consensual mixed parentage. Due to their social positioning, women were denied the choice to keep their children and had to forcibly leave them behind since, supported by the laws, the father had absolute custody of the child.

As Butalia points out, children came to occupy an ambivalent space where they became community property while also inheriting their mother’s subaltern status.

‘Margins’: Dalit lives during partition

In this section on Dalit lives, Butalia comes face-to-face with her caste privilege and realises the reality behind the facade of the Gandhian term ‘Harijan,’ the children of God, which although she still continues using interchangeably throughout the section and yet it becomes evident that such was not the case on the ground.

The ‘Harijans,’ were othered by the Hindu community and also refused to identify themselves as either Hindu or Christian, which ironically in some cases helped them to escape the brawl between the religious communities. Their landlessness and labour class identity also helped in this regard. But the major impact was that in this othering from the community, there was no place to go and no one there to help them.

Butalia also notes a sense of closeness that arose between the Dalits and Muslims owing to their oppression at the hands of Hindus, where the Dalits did not feel compelled to fight the Muslims on grounds of their religious identity. The Dalits were a heterogenous group with a separate identity who felt closer to Hindu and Muslim camps at different occasions.

What Butalia highlighted in this section was the sense of alienness and separation that ‘non-Hindu,’ identities felt from the idea of India, which included not just the Dalits and Muslims but also Christians, Sikhs, and other communities.

Dealing with the memory of partition

In her final concluding section, Butalia credits her feminist sensibilities and the practice of feminist historiography as a parallel and subversive space against male historiography in driving her to this project of unearthing the many layers of silences and unheard histories of the subaltern and bringing it to a fruitful end. In this entire project of searching for the voices of the women, she found the voices of many other subalterns who had been silenced. She reiterates that she wishes that these personal narratives and histories be placed alongside the conventional history in order to supplement a fuller account of the partition.

There were many problems that she ran into while trying to deal with the trauma and fragmented memories of the partition without being invasive. And yet, suppressing and erasing the memory keeps you suspended in an unhealed, stifled state. It’s only when one remembers and confronts the truth that one can truly move on, heal, and forget.

Reading the silences, listening intently to the voices of those denied space in the partition discourse, coming face to face with the many truths of the partition, and understanding the nuances of this historical event is an extremely complex feat that ‘The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India,’ manages to take on.

About the author(s)

Sarah (She/Her) is your local student journalist and writer pursuing her Bachelor's in Literature from Delhi University. She seeks to strike a balance between a chaotic chronically online gen-z and an insatiable learner. At the risk of coming across as cheesy, she quotes Oscar Wilde on being asked to introduce herself, "To define is to limit."