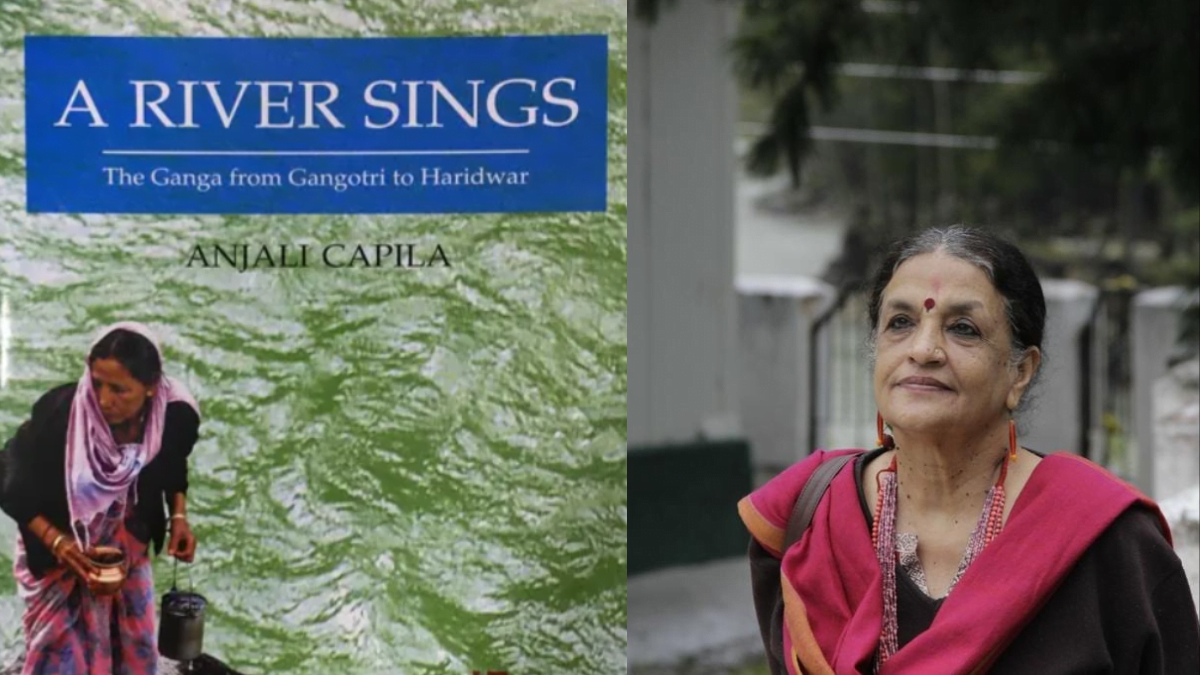

In this book, Dr Anjali Capila has presented the mystic to stage an academic discourse on the cultural dynamics of what is said and felt about the river Ganga by people living on her banks. She shares that this book has been written on the directive of the revered river Ganga herself.

Further, she reiterates that this journey she undertook along the routes following the river had a profound emotional effect on her.

Mother Ganga: a sacred and mystic force of nature

Dr Capila owns a philosopher’s and observer’s eye and has documented songs and hymns sung by women living on the banks of the river Ganges. She uses a narrative and descriptive style as a methodology interviewing a gamut of population cohorts whose lives are deeply intertwined with the river.

Women, men, young adults (18-25 years of age) of the villages, priests, saints, musicians, journalists, school teachers, school pupils, people involved in theatre groups and NGO activists were the respondents for this research. These songs, anecdotes, folk tales, rituals, focus group discussions and in-depth interviews helped in deciphering the way these women position the sacred river Ganges in their lives; through sustenance, livelihood, spirituality, recreation, navigation and social activities.

Dr. Capila was initially ignored by the riparian women when she asked them to sing and explain the words and phrases of their songs on the river. The women turned away this request justifying that a woman from the plains cannot relate to what the local mountain women sing.

The author shared that her drive to document and draft this ethnographic research-based book was fuelled by a dream she saw while asleep, where a woman in white appeared and said to her, “Just like you listened to the songs of the women of Garhwal Himalayas, listen to the songs of this river too.” It turned out that women sing what Goddess Ganga asks them to sing, so they did not need convincing further as they too believed that Goddess Ganga asked for this book. The women said, “Since the menfolk do not want to understand this connection, we sing in the forest as the trees listen and the clouds come down to give their homage to the words mother Ganga sings through us.”

These mystical undercurrents were understood to then be part of the “Document the Riverine Culture” project of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for The Arts (IGNCA) which supported Dr. Capila’s research for this book. This participatory research project was also the PhD thesis of Dr. Capila. The book therefore follows the academic format and structure of a doctoral thesis that has the introduction, methodology, locale, data collation in the format of findings, and data analysis section with a way forward chapter at the end. This documentation is about Himalayan Ganga folklore where the author along with her documentation team records that the river needs prompt and stringent action that would free her from the present age of commercial apathy resulting in pollution, ecological vulnerability and age-old cultural bondage steeped in mythology and patriarchy.

Riverine songs echo riparian women’s voices

The book is conceptualised into five chapters each highlighting a central theme. The first chapter presents the voices of the river which delves into the mythological connection of the river and its journey of worship in various forms. Focussing on “Ganga Avtran” or the river’s descent, from heaven onto the earth many different tales are spun on how and why Ganga came to earth.

The more popular is the story of Bhagirath, who offered penance and sacrifices to request the river to flow through the mortal world to revive the ashes of the 6000 sons of his ancestor King Sagar or the ocean. Bhagirath led the opulent Ganga from the Himalayan peak to the ocean but only after Lord Shiva controlled her force by taming her on the thicket of these ascetic hair terraces. This is the taming of the life-giving resource or the mother river by Patriarchy, which is aware of the regenerative power of water, and binds this force within the male extension to make a norm that gets etched as an object and symbol of reverence and worship.

The Himalayan women in their songs catalogued and numbered in the book, question their mother, Ganga, “How can you survive the cold, tied to the locked hair of Shiva.” The lyrics of the song show a deep understanding of the feminine energy which is resilient and gritty enough to survive the rugged terrain and inhospitable climate and continue to nurture the family by warmly feeding it as well as serving a community after being transported from her heaven to the land of mortality. The song reflects acceptance of the Indian woman being uprooted from her natal home and planted in the marital home where she ignores harsh actions to go on performing her duty unwaveringly and responsibly.

Another myth as cited by Dr. Capila states that Ganga is the source of water for the whole earth and she replenished the waters of the ocean after sage Agasthya had swallowed them. These innumerable references and legends from Hindu scriptures in which the river is an embodiment of a deity are referenced and translated in the first chapter.

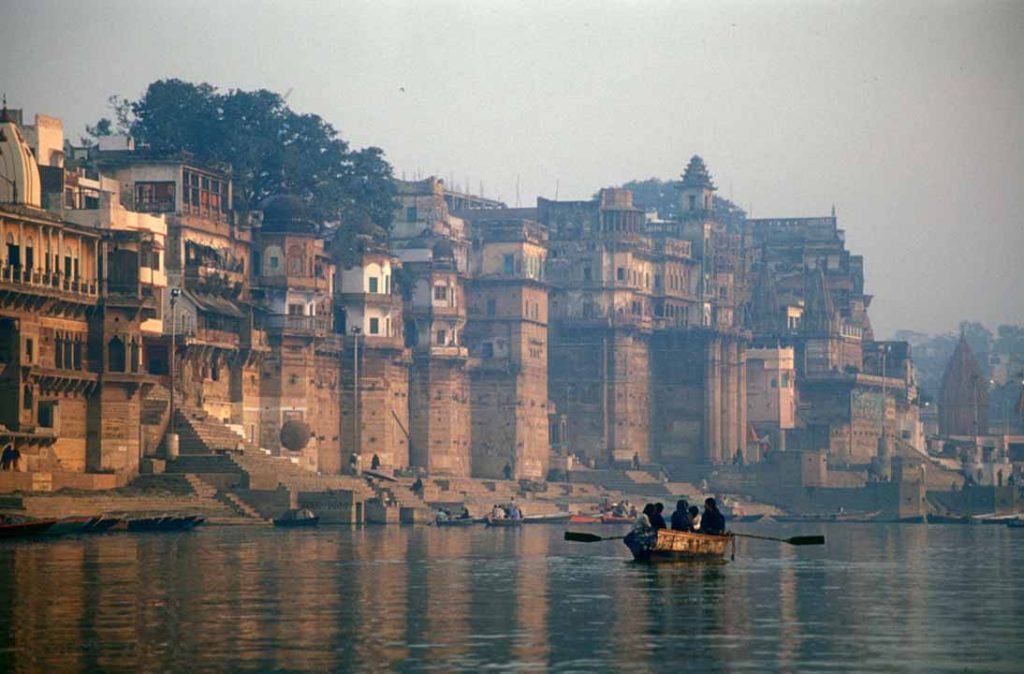

Chapters two and three emphasise the various festivals that are celebrated keeping the river Ganges as a locus and the relationship that women have with the holy river respectively. The narratives and songs from the field allowed the author to categorise these emergent themes which were made into thematic chapters. The author is witness to the year-round festivals praising and worshipping the glory of the Goddess Ganga across the 350 kilometres of the journey she travelled.

‘Unhappy‘ Ganga in the grasp of technology and capitalism

The subsequent chapters namely number four and five are a travelogue to transcribe and translate what the river narrates and adds essence through the human habitation living on its banks at the districts of Uttarkashi, Tehri Garhwal, Pauri Garhwal, Dehradun and Haridwar comprising the Bhagirathi Ganga Valley in the state of Uttarakhand. The author and her research team traversed many small locales, temple towns, cantonments, and villages beginning at Khadi and ending at Haridwar to hear people’s diverse voices and evidence of the state of the river across the changing geographies.

The impact that modern civilisation manifestations and technology have on the river’s fragile environmental balance has been explored in these chapters. The river is unhappy that her waters are dammed through barrages and hydropower projects that have made the flow of her sparkling high-oxygenated waters into stagnant slush that includes submerging vast tracts of land that has increased the susceptibility to landslides compromising her ecological integrity. The water of the river does not come from only the glaciers but through a network of smaller tributaries that connect the river laterally and from monsoon rainfall. Non-structural methods to retain her lateral connectivity can still reformat the exchange of energy, nutrients, and biota between terrestrial, wetlands to strengthen the river ecosystem.

Local people have a history of resistance to protect the river. The tree hugger or Chipko movement has been a more widely known movement than other local ways of organising and collectivising people to govern the natural resources that are fostered by the holy waters. Mortal life is said to have attained salvation if a person or a living entity dies with the flow of this river. The author speaks about women dying by suicide by jumping into the river when social norms and domestic violence sucks away their endurance and they succumb to their mental health state of feeling hopeless and dejected. It is symbolic in that mother Ganga accepts everyone in her embrace and stride, even the ones who have no place to go.

Case studies into the lives of mountain women depict the struggle that is put up against the extractive and non-restorative commercial interest. The flow of the water is celebrated through different festivals to challenge the winds of change by promoting a riverine culture that lives through an experience to give the right to the river to flow and thrive with a cosmo-centric worldview that shows up in parts through interviews and focus group discussions on revival of culture and reverence to uphold the dignity of the river.

The epilogue chapter presents the hope for understanding what the river sang and continues to convey in her manifestation of the hill woman’s sacred oneness in her everyday life. It conveys that the commercialisation of the mountain and the river; trivialisation of religion and culture is a deprecation of our self.

A river runs through the socio-cultural milieu of Garhwal Himalayas

The unique documentation has evolved from the participation of local people who have gathered around the research team to represent the concerns of the river which have been washed away by the current development paradigm. The book depicts the journey of the team from Gaumukh (the river’s genesis from Gangotri glacier) to Haridwar not just in words but through photo documentation as well as freehand illustrations and sketches etching the beauty of the river and its ecosystem as a visual delight. The organic conservations especially of the women participants, the poems and native songs in local dialects have led to the unravelling of the thriving riverine socio-cultural milieu. Voices of the river is represented by women as well as men and children bringing forth their perspectives and ideologies, showcasing the symbiotic relationship they have with the river.

The religious and non-government organisations that facilitated contact with women and women’s groups were largely under the management of men, just like the river Ganga is managed by Shiva. The author does convey that the river and the women at her banks are stifled in the management of her regenerative energy, yet she has not utilised words like patriarchy as these perhaps were not used in the locale of the research area. Even without the use of words that were constructed to understand extraction, the author focussed on benevolence and the force of the river to convey the hope that will keep the river singing in times to come.

This book is a treasure trove for posterity; for anthropologists, sociologists, philosophers and common people, as it upholds, chronicles and interprets the various aspects of the intangible cultural heritage of the Garhwal Himalayan riverine civilisation, centring on the river Ganges.

thanks for this article..!!!!!

An interesting and valuable study. It is sad that though women are so integrally connected to the Ganga, they ,along with the river would be unhappy at the way things are turning out.Difficult to replenish all that we are losing.

Thank you, Shivani.