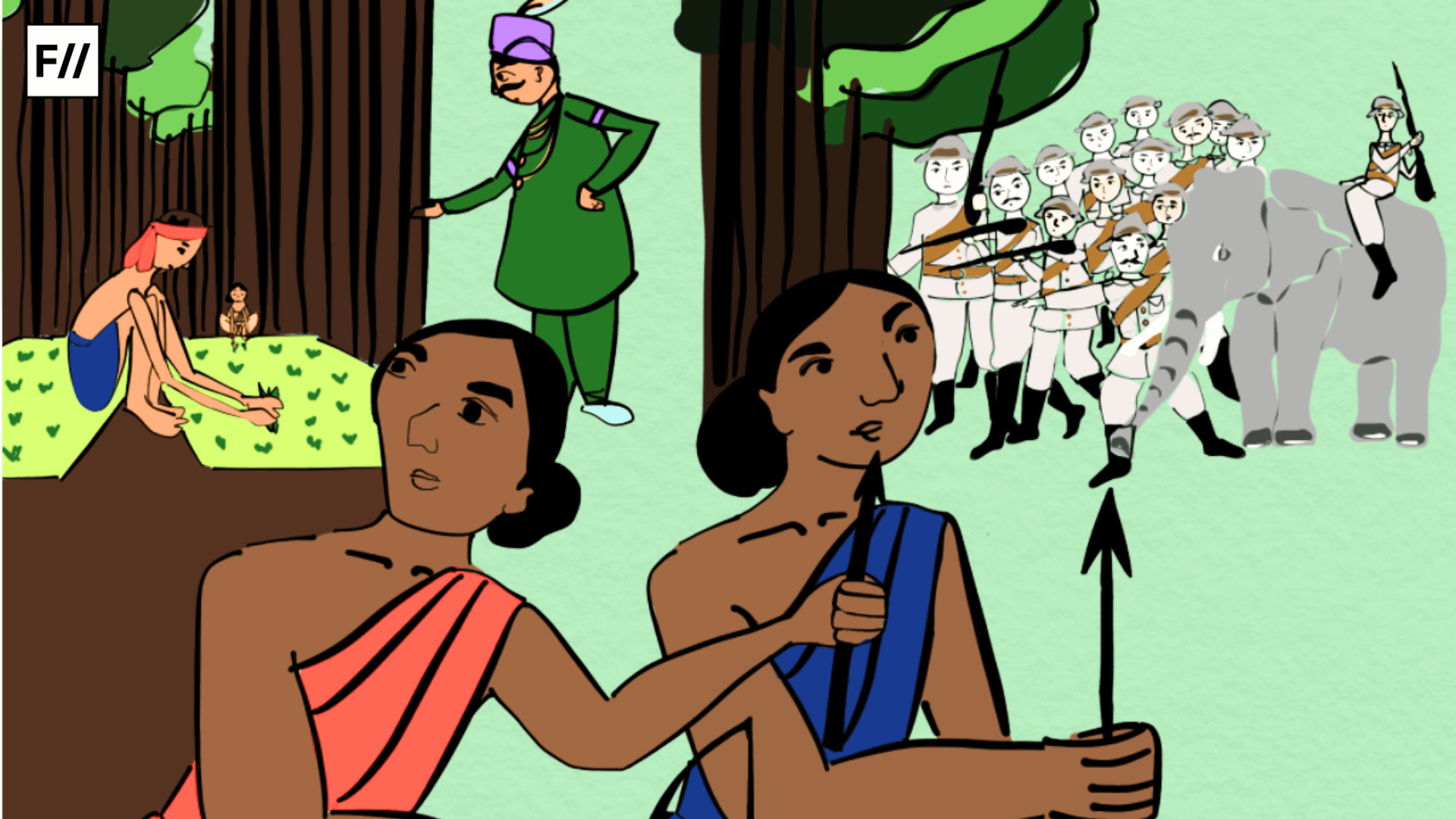

Tribal groups are a distinct social category in India, with considerable diversity but share a blanket of constitutional protection and, as a result are insulated from the mainstream. Tribal women are at the intersection of two of the most disadvantaged groups in Indian society, suffering from sociocultural, political, geographical, and historical disadvantages that have hampered the growth and development of both tribes and women in India.

Tribal customary rules govern important aspects of gender interactions in marriage and family, such as the transmission of property rights via inheritance (intestate succession) and will (testamentary succession).

Most tribal societies’ inheritance laws are customary and uncodified, consisting of a distinct collection of norms, practices, and usages that have been observed regularly over time. Tribal customary rules govern important aspects of gender interactions in marriage and family, such as the transmission of property rights via inheritance (intestate succession) and will (testamentary succession).

However, the question of women’s access to property is a complex one, shaped by a multitude of factors that include religion, marital status, kinship rules, presence or absence of siblings, nature of property in question, tribal status, etc. The Scheduled Tribes and Other Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act of 2006 establishes inheritable rights in forest land, still the uncodified tribal customary rules sometimes deny women the right to inheritance. Tribal women who aspire to own and access land and seek inheritance rights for this land must negotiate a complex social and legal terrain in their pursuit of justice.

Land inheritance vs gender equality

The Hindu Succession Act (HSA), 1956, and the Indian Succession Act (ISA), 1925, which provide the legal inheritance framework for Hindu, Christian, Parsi and Jewish communities as well as those married under the Special Marriage Act, 1955, explicitly exclude their application to tribal communities. Preservation of customs that largely govern ancestral property in the indigenous communities is a major reason behind exemption of STs from the two succession Acts.

Most tribal societies in the country are patriarchal in nature, where inheritance rights devolve only in the male lineage. Here, the tribal women do not enjoy equal entitlement rights as their male counterparts. The All-India Report on Agriculture Census 2015-16 reveals that only 16.7 per cent of ST women possess land when compared to ST men, who hold 83.3 per cent of it. However, what must be kept in mind is that keeping customs intact should never act as an impediment for promotion of gender equality.

As demonstrated, viewing tribal women’s right to inheritance from a purely formal equality perspective tends to overlook the complex and distinct relationship of property, community, family, and self in tribal communities. Besides, inheritance rights are not the sole source or route through which tribal women exercise control over property. Traditional customary practices of gifting smaller pieces of landed property to women as security during marriage, or access and the usufructuary right to land also need to be taken into consideration.

Traditional customary practices of gifting smaller pieces of landed property to women as security during marriage, or access and the usufructuary right to land also need to be taken into consideration.

In the long run, women’s large-scale participation in decision-making mechanisms, and holding decision-making positions in local self-governance mechanisms, along with their capacity building, are also key to their effective control over property.

Judicial responses towards this injustice against tribal women

The judicial application of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 (HSA) to provide inheritance rights to tribal women has significant implications. The courts have extended the provisions of the HSA to tribal women, reasoning that they are ‘sufficiently Hinduised‘ and therefore eligible for the application of Hindu law.

The judicial application of the HSA to tribal women also runs counter to the constitutional recognition of tribal autonomy and self-governance, and it may perpetuate gender inequality and discrimination within tribal communities. It has also forced tribal women where they must choose between retaining their tribal identity and securing inheritance rights through ‘sufficient Hinduisation.’

They either must retain their tribal identity in the face of a discriminatory customary law of inheritance and lose their rights, or they discard their tribal identity, plead, and prove ‘sufficient Hinduisation‘ to secure inheritance rights. If a tribal man can retain his tribal identity and enjoy in inheritance rights, why should tribal women be forced to trade one off for the other?

The unfairness is exacerbated by the fact that proving ‘sufficient Hinduisation‘ depends on the quality of evidence elicited and produced before the court, including documentary evidence and witness testimonies. This, in turn, requires quality legal representation. Most courts are inclined towards placing the burden of proof on the woman seeking inheritance rights to plead sufficient Hinduisation, rather than on those who refute the same through the ruse of exclusionary tribal customary law.

Most courts are inclined towards placing the burden of proof on the woman seeking inheritance rights to plead sufficient Hinduisation, rather than on those who refute the same through the ruse of exclusionary tribal customary law.

It is thus paradoxical that tribal women, who are poorer and more disadvantaged than their male counterparts, are required to gather enough resources and have the tenacity to procure quality legal services to produce conclusive proof of Hinduisation in prolonged litigation that could possibly go up to the Supreme Court of India. For tribal women who face intersectional discrimination and the combined onslaught of poverty and patriarchy, such a burden may be too onerous to discharge.

The tribal women’s right to inherit land is based on customary law in India and so Section 2(2) of the Hindu Succession Act specifically excludes female member of the Schedule Tribe from the provisions of Hindu Succession Act. Even the Supreme Court of India in the case of Madhu Kishwar and others (Petitioners) v State of Bihar and others (Respondents) (1996) while recognising that the customary law of succession was discriminatory to women refused to strike it down.

The decision held that it was not desirable to declare customary law to be contrary to constitutional Rights of women under Article 15, 14 and 21. In Kamla Neti (Dead) V. The Special Land Acquisition officer and Ors the SC of India called upon the Government to investigate the provisions of Hindu Succession Act and change them to provide right to survivorship to tribal women in lines with the other non-tribal women. The court held that to denying equal rights to tribal women even after 70 years of coming in force of the constitution of India is against the spirit and values of constitutional values.

The Madras HC in a recent decision has made it clear that tribal women in the state are not excluded from the provisions of the Hindu Succession Act and, therefore, they cannot be denied the right to inherit family properties. Refusing to accept a contention that ‘Section 2(2) of the Act ..nothing contained in this Act should apply to members of Scheduled tribes…‘ the Court held that when the custom and usage are not established then central government must notify to that effect that tribal women will get access to equal shares in property.

To preserve the tribal community’s autonomy and self-governance, the adjudicatory forum of first instance, through which a tribal woman seeks her inheritance rights, could be the gram nyayalaya (village court), mandated to be established by state governments under the Gram Nyayalayas Act, 2008.

Enacted specifically to provide citizens access to justice at their doorsteps, village courts were to be established at the grassroots level to adjudicate on civil and criminal cases, but this 2008 Act is poorly implemented. The Supreme Court noted that only 11 out of 28 states have taken steps towards establishing such village courts. A traditional forum for adjudication that is familiar with and rooted in local customary practices must be made accessible to tribal women.

NGOs in the area have been highlighting these issues for the past few years, based on their surveys and experiences. In fact, several alternative ways of tackling this issue have also been discussed and action taken on a few fronts, such as filing several cases in the local law courts, with a view to setting precedents that would benefit all Adivasi women.

A suggestion was for the central government to declare by notification in the official Gazette that Adivasis would be governed by the Hindu law as provided under section 2/2 of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956. The scope of this act has been widened to include almost all citizens of India who are not Muslim, Christian, Parsi or Jew by religion.

The problem with this option is really a political one, with objections being raised by Adivasi leaders and others about coming under Hindu law. It is however possible to look for options within the existing legal framework such as the Indian Succession Act, Special Marriages Act and so on. Though not comprehensive as a Uniform Civil Code would be, this option could be quicker and benefit Adivasi women across the country.

For any of these to succeed, however, it seems that women’s participation in struggles and organised resistance is crucial. Through concerted efforts at both the grassroots and policy levels can we ensure that tribal women have the rights and opportunities they deserve in India’s diverse and dynamic society.

About the author(s)

Niharika Shaiyam is a BA LLB (Hons.) student at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore. She is deeply connected to her Gond tribal community, one of the largest tribal groups in India, and is passionate about studying and understanding their culture. Her primary interests include promoting child education and empowering tribal women through entrepreneurship.