Kate Raworth has redefined economics in a feminist sense by developing the Doughnut Economic Model in 2017 in her book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st Century Economist. In her book, Raworth highlights the need to move on from decades-old economic theories that consider economy and environment as separate fields and neglect the role of the unpaid labour of women along with the social actions of people coming from marginalised communities. She focuses on the themes of environment and labour in her model while emphasising the importance of changing our economic actions to make them inclusive and sustainable.

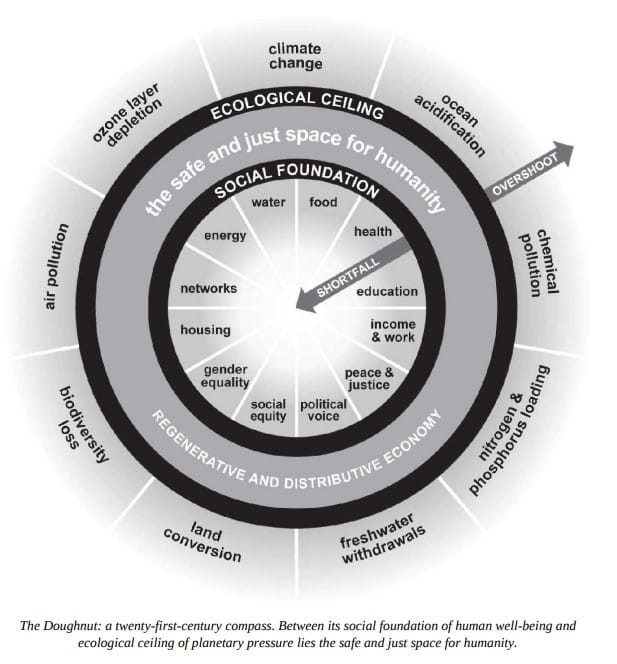

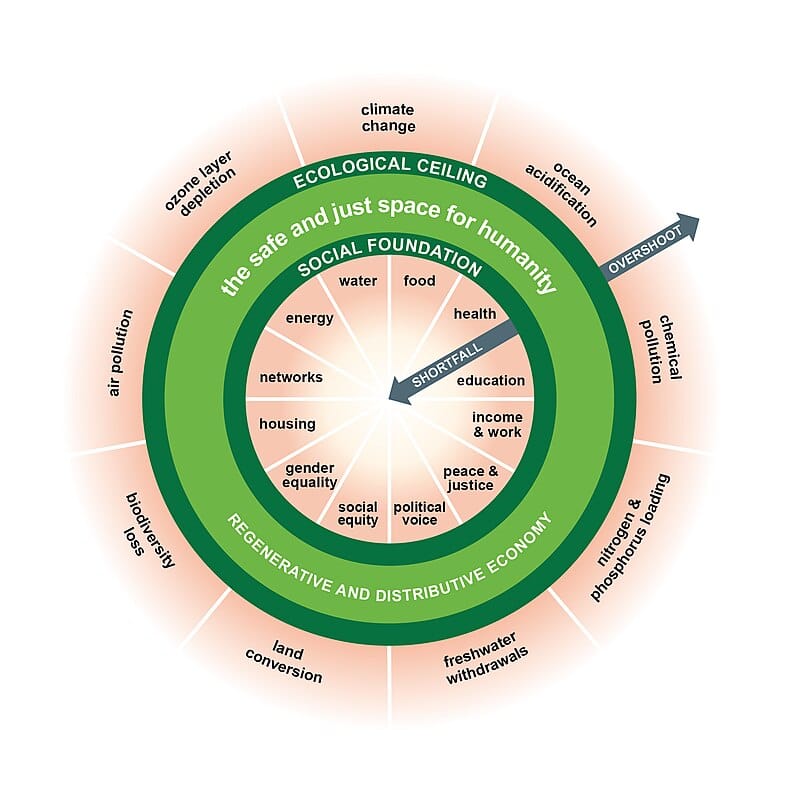

Raworth has represented her model in the shape of a doughnut as evident from the name ‘The Doughnut: A twenty-first-century compass.’

The inner ring of the doughnut represents the social foundation, which includes the twelve basics of life: sufficient food, clean water and decent sanitation, access to energy and clean cooking facilities, access to education and healthcare, decent housing, minimum income and decent work, and access to networks of information and to networks of social support. The inner ring focuses on providing an individual with all these needs while working towards a society that has gender equality, social equity, political voice, and peace and justice. The outer ring of the doughnut diagram represents the ecological ceiling, which includes factors such as global warming, climate change, land conversion, biodiversity loss, and air and chemical pollution.

The doughnut or the space between the two rings is known as the safe and just space for humanity and is considered the ideal situation or space where humans and the environment co-exist together without harming each other. The doughnut falls beyond shortfall and within overshoot, in a space where humans neither lack any life essential nor create intolerable pressure on Earth’s life-giving system. Therefore, the diagram focuses on the requirement for both social as well as environmental stability and represents a sustainable model of development where humanity can thrive without exploiting natural resources

Intersectional Doughnut Model addressing socio-economic inequalities

The Doughnut Economic model is represented in the shape of a doughnut but it consists of seven main principles that are based on the feminist ideas of inclusivity, social equity, intersectionality, and gender justice, along with recognition of unpaid labour, the value of social reproduction, and experiences of marginalised communities which are neglected in traditional economic models.

The first principle is the concept of the Doughnut itself which moves away from using GDP as a measure of progress. It advocates for using the fulfilment of basic human needs that fall in the inner ring of the doughnut and every individual being able to practise their human rights as the criteria for measuring progress which is possible only when feminist advocacy is deployed/used. Aligning with the first principle is the second principle, seeing the big picture, critiquing the neoliberal approach that measures the efficiency of the market by excluding the role played by women in the domestic or private sphere while trying to hide the incompetence of the state.

Advocating for gender equality by recognising unpaid labour by women

The third principle, nurture human nature, makes the model advocate for gender equality as it acknowledges the role of women and marginalised communities in the economy. The traditional economic models rely on the principle of the ‘rational economic man,’ and do not recognise women’s unpaid labour in the form of domestic work and childcare as labour because it does not result in the direct generation of wealth.

However, the doughnut economic model critiques it and sheds light on the need for an intersectional feminist approach to understand how gender, class, caste, religion, and several other overlapping identities of an individual shape the economy of the world.

Along the lines of the previous principle, the fourth principle of the model is to get savvy with systems. Since the majority of the economic policies are seen from the lens of equilibrium, they end up neglecting the inequalities and difficulties faced by women and other marginalised communities in the job market and labour force. The concept of equilibrium moves away from the sad reality of rising job insecurity, the existence of the gender pay gap, and the disparities faced by marginalised communities. Therefore, the Doughnut economic model calls for the creation of policies that are empathetic to the economic resilience of the people and provide social safety nets.

Acknowledging unequal existence of inequalities and its impact on the marginalised

The fifth principle, design to distribute, provides a critical outlook towards how economists claim that inequality is an economic necessity while referring to the Kuznets Curve. Economies are complex systems and hence, have varying influence on different identities. So, when traditional economic models tend to justify inequality, this principle of the doughnut model brings back the attention of the people towards how only certain groups are and have always been at the centre of inequality and constantly deprived of their rights and dignity while contributing significantly to the economy.

The sixth principle, create to regenerate, is again an extension of the previous principle but in an ecological sense. The doughnut economic model analyses the economy by linking social and ecological well-being and creating a system that acknowledges how environmental degradation and pollution affect women and other communities such as the Indigenous people more as compared to men. Lastly, the seventh principle, being agnostic about growth, says that a sustainable economy can be created only when there is equity in the distribution of sources and the voices and concerns of the marginalised are acknowledged and taken into consideration during the formulation of inclusive policies which would improve their experiences.

Kate Raworth looks at economics from a feminist lens through the Doughnut economic model as she shifts the focus from neoliberalism and capitalist growth, which prioritises maximising profit over the welfare of people, towards sustainable growth, which prioritises inclusivity, social equity, and the well-being of both people and the environment. She criticises the traditional model of economics by problematising the ‘individual behaviour,’ of human beings which perpetuates inequality and prevents the creation of a circular economy.

Raworth has changed the language in which we discuss economics by advocating for an economic model which is inclusive, operates on an intersectional framework, and aims to balance the social and ecological needs of humans without exploiting the environment and the already marginalised communities.

About the author(s)

Neha (She/They) is a neurodivergent queer writer who illustrates occasionally. A student of media and gender studies, Neha is critical of the patriarchal and heteronormative world around her and looks at it from the political lens of intersectionality. Although socially introverted, you can find Neha getting out of her shell and interacting with people, getting to know their experiences, and analyzing how the biased structure of the society impacts the marginalized.