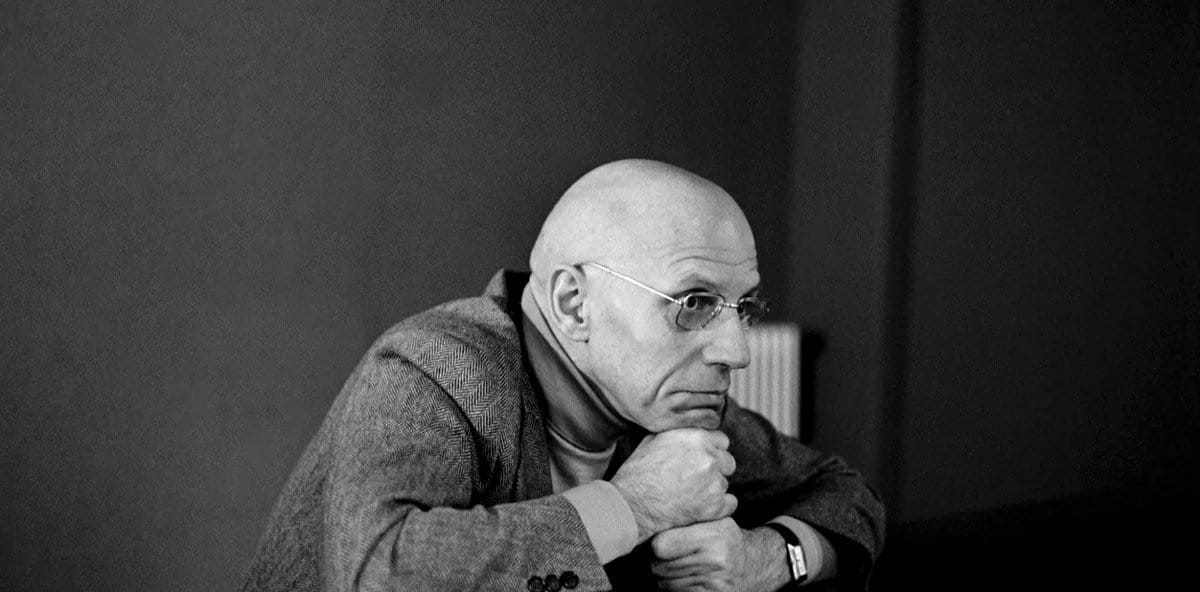

In 1976, Michael Foucault published the first volume of The History of Sexuality, where he discusses a foundational critique of “Repressive Hypothesis.” This hypothesis proposes that between the beginning of Modern history and the Victorian period, there was a culmination of a unique repression of sexuality, corporeality and sex. The cartesian dichotomy of the public and private spheres was most clearly defined in this period where sex and sexuality were subjects of private spheres. Surveillance and censorship dictated these dichotomies where the dominant narrative was being encoded in popular morality.

Michael Foucault in his critique argues that rather than a suppression of the discourse of sexuality, there has been a proliferation of discourses. It was through this proliferation that rather than being suppressed, the discourse around sexuality was being constructed by prevailing requirements. Foucault considers that merely historical analysis is an insufficient tool for the discursive study of the past. His methodology goes beyond the socially constructed binary oppositions to “excavate the archives” and “write a history of the present.”

The synchronisation of Puritanism and Capitalism in 17th-century Europe

According to the first volume of The History of Sexuality, Foucault argues that with the rise of capitalism labour that was productive was hierarchies into a gradation. Physical labour was supposed to be a productive input to harness economic growth at an exponential rate. Subtle scrutiny got embedded in the society where the subjective identity of individuals was supposed to be an aid to capitalist productivity. Aspects that were a hindrance to this project or rather were merely unproductive were to be exterminated.

Gayle Rubin, in her widely-cited essay, “Thinking Sex,” expands on how the notion of Victorian Morality came to be consolidated. She writes, “There were educational and political campaigns to encourage chastity, to eliminate prostitution, and to discourage masturbation, especially among the young. Morality crusaders attacked obscene literature, nude paintings, music halls, abortion, birth control information, and public dancing.”

This post-industrial expedition gave rise to a public space where madness was carefully ghettoised through institutionalisation. Foucault focuses on how sexuality was being adapted in this ambit where the body must also be sexually productive in compulsory heteronormativity. Sexuality that prioritises pleasure over procreation was carefully othered, and the disciplinary institutions participated in an exhaustive indoctrination of these “norms“.

The bourgeois ethics and puritan theology seeped into one another. Between the 17th to 19th centuries, the Church became another disciplinary institution to encode the morality of heterosexual monogamy. A simultaneous criminalisation of homosexuals and hermaphrodites was on its way to regulate the discourse of sexuality. Gradually confessions were made an obligation. Foucault also unveiled the subtle mechanism through which power structures are perpetuated. This gave rise to an order of discourse where madness, the opposition between truth and falsity, and institutional ratification became procedures of exclusion.

The social construction of sexuality

According to Foucault, the body is also a discursive construction which perhaps cannot be a site of resistance. Foucault’s social theory places the self within the discursive and power structures of society. He was unveiling the juridical power relations that are beyond the ambit of the physical body and that aim to construct a “docile” body.

Shelly Treiman writes in On the Government of Disability: “Although juridical power appears to regulate political life in purely repressive terms by prohibiting and controlling subjects, it actually governs subjects by guiding, influencing and limiting their actions in ways that seem to accord with the exercise of their freedom.” This is to say that subjects are more than often reproduced according to the requirements of the hegemony.

In the first volume of The History of Sexuality Foucault also conceptualised the terminology – “Biopower.” In the body theory of Foucault Individuals are constituted by power and its exercise is graffitied on their bodies. For illustration, it is the power of gaze that enables the discourse of ableism and patriarchy through a close regulation of the bodies of individuals. Foucault considers this Biopower an essential and strategic element of governmentality. Contesting the theory of repressive hypothesis he posits that the proliferation of discourses around sexuality and sex was an illustration of both governmentality and biopower. Manuals and pamphlets that discussed the regulation of children’s sexuality, venereal diseases and human sexual anatomy exemplify this and this is made possible only because of the system of repression.

Docile bodies and Governmentality

Foucault continues this “genealogical” understanding of sexuality in a series of other adjacent concepts including biopower, docile bodies and governmentality. In Discipline and Punishment (1977) he illustrates through the concept of “Panopticon” that a gaze of surveillance implicitly controls and regulates the lives of subjects. These “disciplinary technologies,” produce bodies that are under the purview of hegemony. He writes, “A body is docile that may be subjected, used, transformed and improved.”

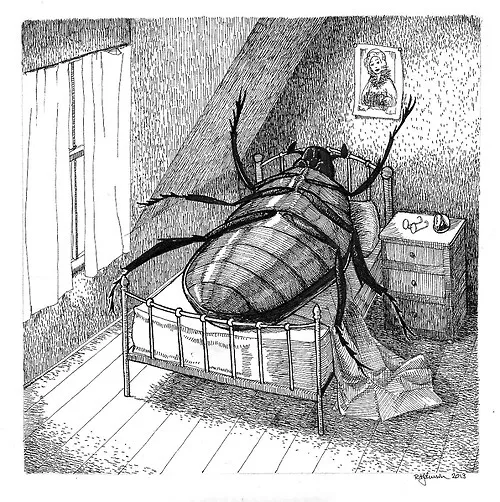

Illustrating the “repression” in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis

This aversion to pleasure was not only restricted to the domain of sexuality but also seeped into everyday lives where any form of pleasure was seen to be profane. The existential angst and guilt in the writings of Kafka can be a suitable example of this. In the narrative of The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka, the protagonist Gregor Samsa is expected to fill the saving coffers of the family in a cash economy where any deviation from the assigned performance attracts a gaze that dehumanises the subject. The biopower not only regulates his sexuality but any pursuit that is beyond the mercantile middle-class aspirations.

Foucault’s writings give an interesting perspective on the relationship between power and knowledge. The knowledge of the controlling and pervasive power of the authority reveals the duality that the state continuously develops apparatus to control the subject it claims to represent. Hegemonic concepts of sexuality, ableism, and heteronormativity, all seem to be problematised. Foucault gives us a beginning to a series of questions that can reject past conceptions of morality and envision sexuality as something free and uninhibited, as Foucault calls it “garden of earthly delights.”

References:

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. Pantheon Books, 1975.

- The History of Sexuality. 1976. Penguin Books, 1998.

- Kafka, Franz. Metamorphosis. 1915. Arcturus Publishing Ltd, 1915, www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Kafka_Metamorphosis.pdf.

- Neira Dev, Anjana, editor. A Critical Reader for Literary Theory . Pinnacle learning , 2017.

- Rubin, Gayle. Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. 1984.

About the author(s)

Anchal is a writer, poet and spoken word artist based in New Delhi. Her works have been published on various platforms, including Enroute Indian History Blogs, Indian Review E-Journal and department and annual magazines of Miranda House, Kirori Mal College and Gargi College. Currently, she is pursuing an MA in English at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and loitering around the city.

I would like to appendage few things in the article. You could have elaborated the conceptuality of ‘Dispositif’ a term elicited by Foucault. For Foucault ‘ Dispositif’ is an institutional control that control and govern our life through different disciplinary regime pervading across the spatial template of space and place. Secondly panoptic or panopticism is a concept envisaged by Jeremy Bentham which was taken by Foucault later on to stitch his argument in the production of power through the coordinated geometry of gaze and disciplinarity. Perhaps you could have mentioned Bentham before framing your sentence by citing him accordingly.

While using extremely derogatory words like “Hermaphrodite” it’s always best to acknowledge it’s derogatory nature and perhaps point it out so that people don’t end up believing that it’s a neutral term when it is not. One needs to be aware about the sensitivity of words, specially as a writer.