“Iske sath upari hawa ka chakkar hai, isliye beemar chal rahi hai ye,” (she has been influenced by negative spirits which is why she has been sick) informed the husband of a 25-year-old woman, Sunita who had recently experienced the stillbirth of her baby. Since then, she had been in a near-comatose state and frequent fainting spells. The family consulted a faith healer who informed them that the tragedy was a result of a jealous relative who had cursed her through black magic. On his advice, they performed a ritualistic ceremony to ward off evil spirits from her and relieve her symptoms. This ceremony gave her temporary relief but the symptoms returned. When she consulted a doctor, she was diagnosed with depression and prescribed anti-depressants.

Once in therapy, she finally shared the story of her loss. ‘Sab bolte hain bhul jao aur aage badho par itna asaan nahi hai ye karna,’ (everyone tells me to forget and move on but it’s not as easy to do so). Among the different treatments, whether through a faith healer or a doctor, she had not found an opportunity to express or even acknowledge the burden of the grief she had been carrying.

Sunita’s story is one among many that highlights the complex interweaving of belief systems tied to caste, class, and religion. It illustrates a familiar pattern where individuals are often presented with binary choices to address their suffering and even those are often decided for them by others in their community.

The intersection of faith and mental health

In collectivist societies like India, family and community beliefs play an influential role in shaping how people perceive and address mental health challenges. Many emotional or psychological issues are explained through the lens of supernatural or spiritual beliefs, which have been passed on from generation. Stories about curses, devatas (deities), and ancestral spirits are common and carry significant weight.

Emotional distress is often seen as a consequence of ‘bure karma,’ (past misdeeds). Deviating from religious or familial rituals can also be considered to trigger mental illness. In one family, skipping a ‘puja,’ (ritual) was believed to be the cause of sickness for a family member.

Such belief systems are reinforced through community validation. “Ye toh humne bachpan se suna hai” (We have heard these from our childhood). When individuals experience phenomena that are seen as spiritual, such as the voice of an ancestor or visions of religious figures, these experiences are woven into collective beliefs and are embedded in a cultural context that values tradition and community practice.

How stigma and marginalisation limit access to mental health care

India’s social frameworks of caste, class and religion are embedded in a hierarchical structure. As such, individuals at the fringes of each of these social categories often have to bear the brunt of stigmatisation. The combination of stigma, economic burden and cultural marginalisation leaves little room for choice and therefore many prefer to rely on community healers and faith-based practices.

In another example, Shehnaz, a 20-year-old woman from rural Uttar Pradesh, began experiencing symptoms of hallucinations and delusions shortly after her marriage. Her in-laws believed she was ‘possessed,’ and consulted a faith healer. When her condition did not improve, her condition was viewed as a ‘failure to recover,’ on her part and her in-laws demanded she return to her parent’s home. Later it was diagnosed as schizophrenia, a treatable psychiatric condition.

However, due to a lack of limited understanding of mental health and the high cost of medical treatment, Shehnaz faced further ostracisation and isolation from her community. It also ended up putting the onus of the problem on the patient with few options for effective care.

For those in higher socio-economic or urban settings, there is greater exposure to biomedical approaches, allowing them more freedom of choice to avail different treatment options. This openness, along with financial means and access to information, enables more variety of healthcare options, in contrast to the more restrictive and stigmatised options available to marginalised individuals.

Shortcomings of the biomedical model in addressing culturally interwoven beliefs

Given the diverse and culturally rooted beliefs that inform mental health perceptions in India, the primarily Eurocentric biomedical model of care falls significantly short in addressing the diverse needs of individuals. Being more fixated on “cure” than “care” tends to uphold the Western concept of holding the individual responsible and pathologising their felt distress. It largely ignores the systemic forms of oppression that make up the social determinants of health such as colonialism, chronic poverty, capitalism, gender or sexual violence, environmental toxins, etc.

One significant impact of colonisation is on the usage of language. Patients often use localised or native terms to describe their experiences and such terms are a part of a rich fabric of the culture they originated in. However, through the imposition of largely Anglo-centric medical terminology, a lot of the meaning behind the terms gets lost in translation. In many cases, these terms don’t even have a direct English equivalent, making it difficult to fully capture a patient’s lived experience.

Part of the issue lies in the healthcare system that compels mental health professionals to conduct assessments and to ask a few standardised questions to examine their “mental status,” and neatly slot them into a specific diagnostic label. This approach leaves little room for genuine curiosity about the person’s unique cultural and personal context and understanding the concerns from their lived experiences.

A common refrain among patients describing their cultural beliefs is, “Hum ye sab doctors ko nahi batate kyunki wo nahi samjhte hain” (We don’t share these with the doctors since they don’t understand them). When medical professionals, shaped by a biomedical perspective, ignore these cultural contexts, they risk misdiagnosing or disregarding the deeply personal and community-rooted sources of distress.

Decolonising mental health care: Bridging traditional and biomedical approaches

With such diverse mental health needs, a culturally integrated approach becomes essential. Colonisation has falsely posed the superiority of Western enquiry, relegating Indigenous and traditional practices to the margins and deeming them ‘backward,’ or ‘unscientific,’ undermining long-standing cultural systems that have supported community well-being for generations.

Neetu, a woman in her 60s, who experienced visions of ancestral figures described them as, “Mere upar hamare kul-devta ka prabhav rehta hai. Wo mujhe sapne mein meri samasya ka samadhan bata dete hain” (I have an influence of our ancestral deity. He comes in my dreams and gives me the solutions to my problems). The family then explained that these are protective spirits who have been doing so for generations in the family. This belief provided her with a sense of connection with her community and reduced symptoms of anxiety.

A decolonial approach recognises the strengths of traditional practices as a part of a holistic approach to care. Both the DSM-5 and ICD-11, frameworks for diagnosing mental health, emphasise the importance of cultural beliefs that may influence symptom expression and call for a comprehensive assessment that respects cultural context. This involves collaboration with individuals’ cultural perspectives and may include integrating medical, psychological, and culturally informed interventions. By recognising them as legitimate and complex systems, we can build a mental health model that is more inclusive, personalised, and responsive to the social contexts of diverse communities.

Community-based narrative therapy: An inclusive model

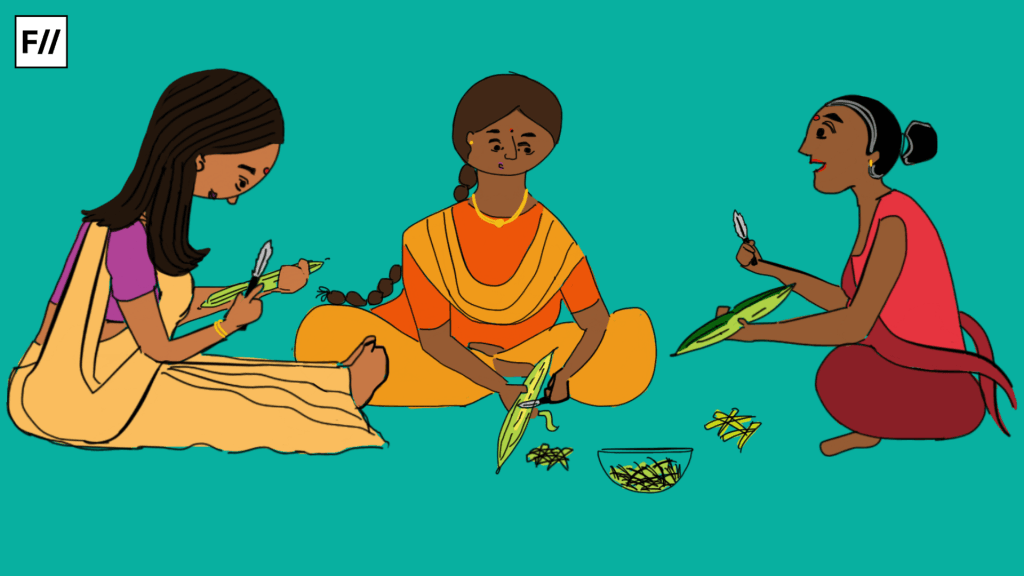

Community-based Narrative Therapy offers an alternative that attempts to bridge the gap between biomedical and traditional methods. This therapeutic approach respects two distinct forms of knowledge— academic and local knowledge and suggests that the exclusion and diminishment of people’s local knowledge is a key contributor to internalised distress. When people’s local knowledge is devalued, it leads to misery becoming an internal experience, that is further compounded when they seek assistance from those who only value academic knowledge.

One key factor is that it departs from a hierarchical tradition where information is concentrated and held by a professional and avoids positioning the therapist as the expert. Instead invites agency from the individuals to shape their narratives within the larger sociocultural context they inhabit. In a community setting, individuals can share their insights, stories, and strategies for resilience without conforming to a prescribed “solution” or path to mental well-being. Instead, they find support in each other, sharing and building upon their collective knowledge in creative ways, through music, storytelling, or local metaphors.

Community-based practices which value collective resilience and cultural knowledge, offer a well of knowledge. The kind that sustains entire communities through droughts and storms. It is not just individuals like Sunita, Shehnaaz or Neetu who draw from it but also those who rely on them and it becomes a shared responsibility to replenish it.

About the author(s)

Mahi Goyal (she/her) is a Counselling Psychologist with over 4 years of therapy experience across both urban and rural settings. She also holds a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Miranda House, DU. At the age of 18, her first novel was published in 2015 titled, ‘Real Illusion’. Her work has also been featured in the 2013 anthology of short stories, ‘Internal Reflection’. She frequently writes on the intersectionality of Mental health with gender & sexuality and human rights as well as literary analysis from a psychoanalytic lens.

❤️ love from a so called Psychologist 👩⚕️