The year 2016 witnessed Shayara Bano approaching the Apex Court, appealing the decision of her husband, who divorced her through the repetition of the word ‘talaq,’ three times.

Media houses formulated headlines highlighting the gruesome state of Muslim women, powerless and hopeless, subjected to the wrath of their husbands. They projected the act of Bano reaching out to the Court for redressal not as a step against her husband but as a challenge to all Muslim men, generalised to be patriarchal, and the deep-seated orthodox tendencies in their religion.

Islamic law, in their narrative, proved to be a disappointment, while the state was hailed as the messiah. However, one must not forget that this very state has been complicit in the violence against Muslim women, isolating them, without paying any head to their deteriorating mental health, as highlighted in “Social Suffering in a world without support” a report by the Bebaak Collective. For instance, in 2021, an app named “Sulli Deals” surfaced on X. The object of the app was to “teach Muslim women a lesson” putting them up for “auction” by circulating their photographs and presenting them as “deals” to be availed. Violence is not merely physical. An omnipresent and omnipotent tool like social media often becomes an instrument for degrading Muslim women.

Contextualising the case in terms of time and space

After over thirty years of the Shah Bano judgement of 1986, which ignored her material needs, disregarded her demand to lead a dignified life while adhering to her religion, and was hailed by the then opposition as a ruling to “appease” the orthodox Muslims for garnering votes, in 2016, Shayara Bano petitioned in the Supreme Court after being subjected to domestic abuse and unilateral divorce through triple talaq. Her legal battle was based on three concentric aspects: illegalising (a) polygamy, (b) nikah halala, and (c) triple talaq in accordance with articles 14, 15, 21, and 25 of the Indian Constitution, thus stirring a tension between personal laws and secular laws.

The judiciary is entrusted to act as a mediator between religious personal laws and constitutional fundamental rights. While two judges out of the five-judge bench perceived triple talaq to be a crucial component of freedom of religion, the other three declared it to be a highly arbitrary tool that can be misused by a Muslim man.

The discussion culminated in the criminalisation of triple talaq through the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, although it was decreed that a valid alternative talaq procedure be formulated within the domain of civil rights. The Act granted a seal of approval, a sanction to the ruling party’s attempt to mark it’s presence in the functioning of the Muslim community to ensure the nation’s security, promoting the belief that if Muslim women (victims) seek the help of the state, they will be recognised as loyal Indian subjects.

In this case, the relation between the woman’s needs and her community’s desires was sidelined, and the hypervisibility of the handful of women who approached the court led to the invisibility of the remaining Muslim women, who perhaps may have employed numerous other means to overcome similar situations of domestic violence and dowry harassment, “khula” (the islamic practice permitting a woman to divorce her husband) being one among such means. In the case of Shah Bano, however, a contradictory approach was adopted, which declared that her interests conflicted with the Congress’s vision for unity emerging from the diversity.

“Rescuing” Muslim women

“Rescuing women” is a phrase that establishes the state as the protector while simultaneously tying women down to and justifying their oppression. Referring to Muslim women as victims can be traced back to the colonial endeavour of rescuing brown women from brown men, establishing their “paternalistic domination.”

Why did the idea of protecting Muslim women suddenly strike the state? The government successfully manipulated Shayara Bano’s personal experience to support the Muslim othering phenomenon. The Muslims are perceived as a security threat to the populace, not capable of being assimilated within the national fold. From a feminist geopolitical lens, the territorial politics involved in the process of nation-building has gendered implications, with “femonationalist” state projects portraying one section of the community as a threat and the other as a victim, based on their “naturally occurring” attributes- men being aggressive, women being weak and requiring help. This also sheds light on the state’s representation of Muslim women as “damsels in distress” awaiting a saviour to relieve them of their dire circumstances.

Sara R. Farris, in “In the name of women’s rights, The rise of femonationalism” argues that “femonationalism is the exploitation of feminist theories by nationalists and neoliberals in anti-Islam campaigns and to the participation of certain feminists and femocrats in the stigmatization of Muslim men under the banner of gender equality.“

A powerful state and powerless women of the Muslim minority

Today, the central government’s vision for ‘Ek Bharat, Shreshth Bharat,’ involves not only an emphasis on unity of the population but also the segregation of the otherised Muslim. The case is a stark example of how politics is gendered, how the law is not neutral but is influenced by the geopolitics within the country- between the majoritarian state and the Muslim minority. In the name of liberating its “Muslim sisters“, the ruling party, posits Muslim men as a threat to internal security and to women, further subordinating the position of women and furthering the government’s vision of a Hindu nation.

The law minister claimed that the Act was only aimed at ensuring empowerment, redressing the injustice, and restoring the dignity of Muslim women and not tied to religion. This statement is a gross under-representation of the electoral landscape of the country, wherein religion and politics are intertwined. Underlying this effort by the state and its organs to rescue and save Muslim women is a political manoeuvre to include the “good” Muslims (women who need to be “rescued”) and exclude the “bad” section of the community (men who are abusive and violent) who pose a threat to the idea of the nation as envisioned by the state. This effort was also in line with the ruling party’s electoral promise to implement a Uniform Civil Code.

The state intended to further the narrative that by escaping the clutches of triple talaq, women could be liberated from oppressive customs and steer themselves towards a progressive life, doing their bit for nation building. This highlights how feminism is used as an instrument for promoting the vision of “Akhand Bharat”. This case illustrates how the Court selectively protects and unprotected members of the same community, placing the women in relation to the state in a way that stresses upon their religious difference- treating marriage and divorce cases of Muslim women as a legal problem.

Sometimes a protector, other times a persecutor

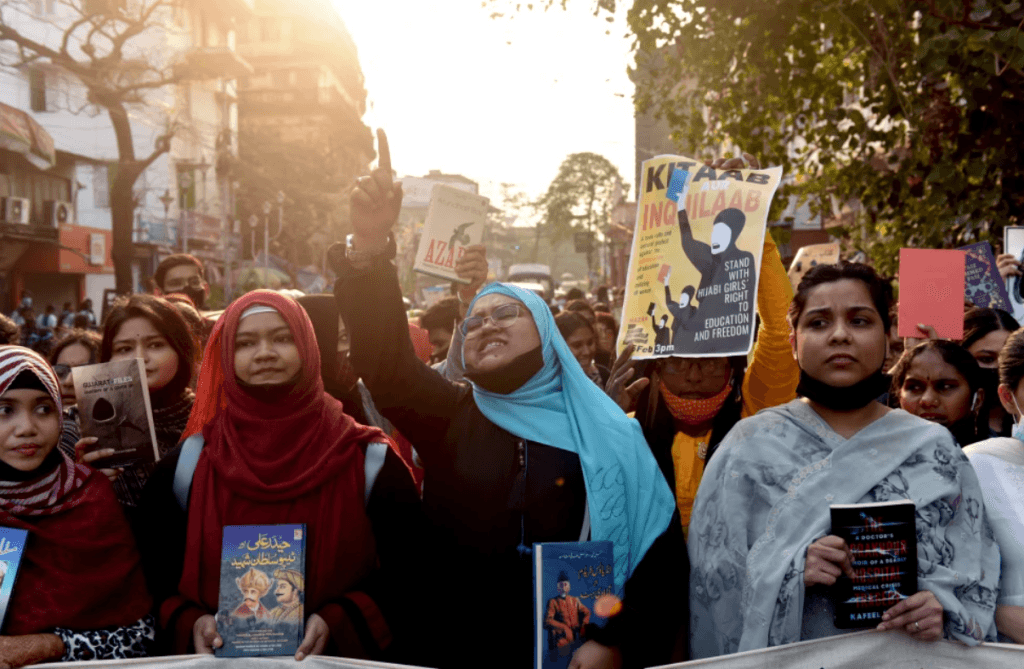

In one instance, we see an effort to “protect” Muslim women, while in another, men wearing saffron clothing and shouting praises for Lord Ram surrounded women wearing the hijab in Karnataka as a means of expressing resentment against Muslims in the state.

This masculinist approach has been propagated by the ruling party in the state as the defining feature of a Hindu nation. When we speak of the making of a masculinist state and furthering of hindu nationalism, it becomes crucial to discuss the hijab ban.

Jyoti Bania, in “Hijab Row as the Reflection of a ‘Hegemonic Hindu Masculinity‘ in the Service of Hindu Nationalism,” argues that the incessant protests to implement the ban exposed a “hegemonic hindu masculinity,” institutionalised and authorised by the state as an instrument of nationalism. This so-called false masculinity is an attempt to strengthen Hindu nationalism, which has as its basis the will to marginalise and suppress Muslims, particularly women.

Invisibilisation of women’s interests and demands

Bebaak Collective, in “Stop The Criminalisation of Triple Talaq,” referred to the Act as “arbitrary, excessive and violative of fundamental rights in the Constitution“, floating the possibility of women being subjected to increased violence and threatening their household and economic security. Selectively attributing their attention to legal cases wherein women can be projected as victims, the ruling party unintentionally reveals how in a Hindu nationalist state, “Muslimness” is only a law and order problem.

Addressing the state, Bebaak Collective, in ‘Criminalizing Muslim Men‘ (2019), argued that “You cannot pretend to save Muslim women, while seeking to bring the Muslim community to its knees.” Underlying the banner of protecting Muslim women is the state’s attempt to declare that only those women who constitute the minority religions need protection, for the Hindus have long granted women “equal” rights.

It is evident how the government becomes a flagbearer of preserving women’s rights and promoting gender equality, only to further its own ends. As a consequence, the concerned women are rendered invisible, their desires and interests are not attended to, as the case acquires a new focus, that of locating the place of Indian Muslims within the state. Therefore, women’s legal demands for justice and gender equity are suppressed within this broader framework of nationalism.

About the author(s)

Syeda Shua Zaidi is a student of B.A. (Hons) Sociology, at Miranda House. Passionate about poetry, filmmaking, heritage walks, social work and all things vintage, you would find her reading the works of Murakami, Khaled Hosseini and Agatha Christie while treating herself to a cup of tea. Firmly a believer of "disagreements are welcome, disrespect is not".