One of the most important subsets of the genre of feminist horror is body horror. Within body horror themes, body issues and reproduction related traumas continue to be the most discussed. In other themes, women display the “femme-fatale” trope by either by being vampires hunting down men or just women avenging their trauma or suffering.

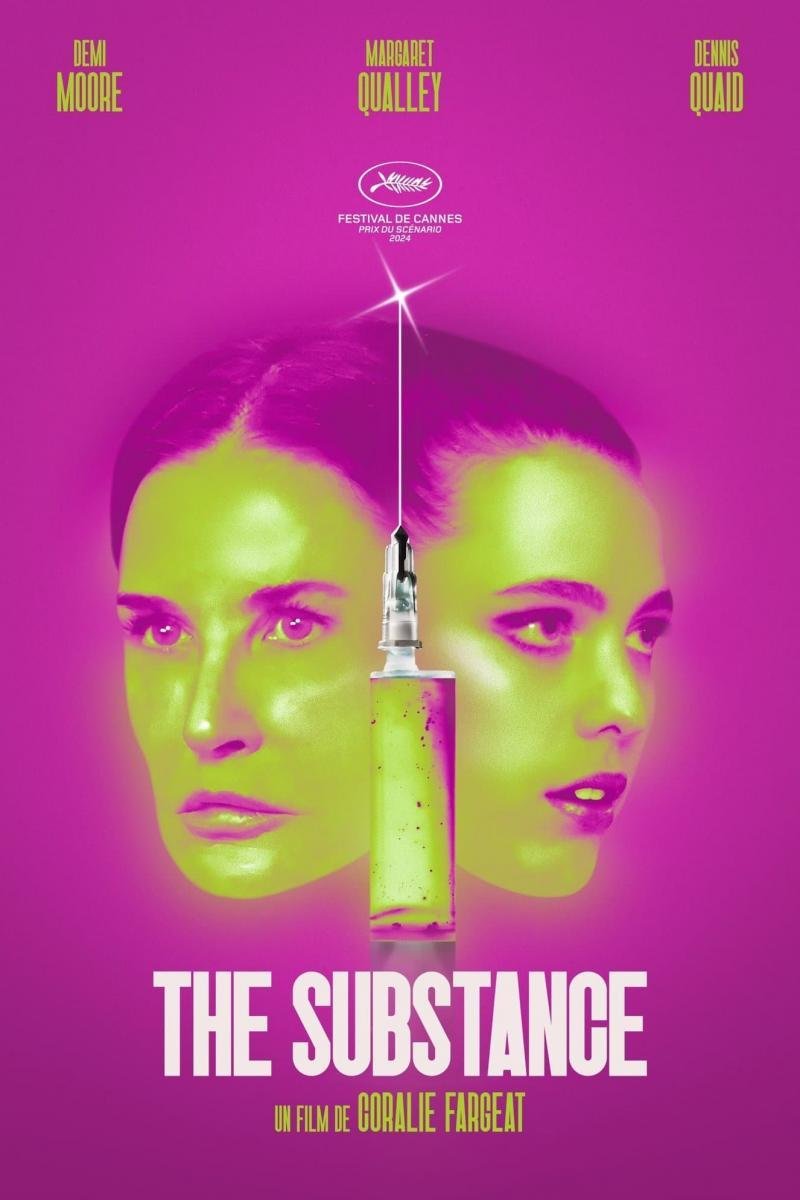

The very recent film by French director Coralie Fargeat, The Substance (2024) provides a sort of screen depiction of women’s issues, via a genre that has been categorised as “satirical horror”.

The films may go back to the 1970s or even beyond, like in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), a woman playing the titular role has been tricked into a marriage and childbearing for ulterior motives, discovering which she starts battling on physical and psychological level till the last scene. In Carrie (1976) we see the plot unveiling with a girl anxious due to menstruation. The larger politics that all the themes combined, whether made responsibly or not, point towards is women’s bodily autonomy and dignity. Trauma, desire, vengeance, etc. are the variations.

The satire on horror

The very recent film by French director Coralie Fargeat, The Substance (2024) provides a sort of screen depiction of women’s issues, via a genre that has been categorised as “satirical horror”. While not a popular dictionary meaning of the term being in place, one could take the liberty to interpret this genre as a set of films with traditional elements of a horror film with smartly subverting the real message and in the process, mocking the very traditionality of the evident theme.

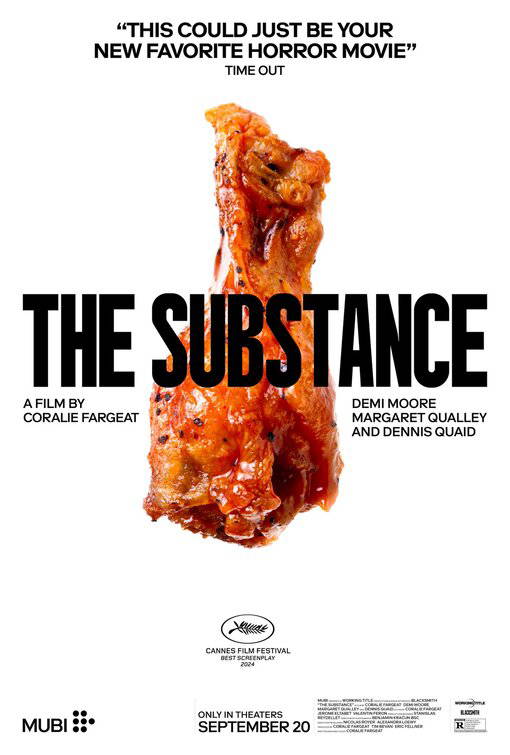

It’s almost meaningless to be discussing the minute-to-minute story or the plot of the film, as the subject of the film comes quite apparent from the trailers and posters. But the intelligence with which each angle is shot and the choice of shades of colors and narratives used in some frames create the difference. The film dwells upon a fading Hollywood celebrity’s desperation to sustain herself in the show business. This makes her order a black-market drug that promises a younger and more beautiful body clone in the conditional situation if both, original and clone, bodies switch every seven days.

The troubles start when both the bodies- which are supposed to be a singular consciousness- start growing apart and hostile towards each other. Eventually, the seven-day balance is disrupted and both the bodies suffer some nightmarish consequences.

Graphic art of the horror

There are some specific scenes and moments through the film wherein the direction and scriptwriting provide a slice of a strong feminist satire and commentary on capitalism. For instance, the sexist producer of the show from which the lead character is being replaced due to her aging is interestingly named as “Harvey” and is shown to be heartless in terms of business.

In a scene he is shown to be gluttonously munching on cocktail shrimps while the lead character is watching him in both disgust and amusement from across the table. The camera zooms particularly at his mayo smeared hands and lips for some second pointing how men can always afford to be eating as much as and whatever they like despite reaping profits out of women’s well-toned and worked out bodies. Men can be out of shapes and yet relevant! Women’s eating can never be as normalised as it is for men.

Men can be out of shapes and yet relevant! Women’s eating can never be as normalised as it is for men.

The cocktail shrimps could be reflecting their expensive choice of food/snacking at the behest of the women doing beauty business for them. Ironically, in scenes where the lead character is indulging in careless eating, it is primarily for setting scores with the younger body clone and not for enjoying the items. This comments on how women never easily get to relish on food or enjoy their sexualities in the capitalist society without there being some context or narrative behind it. In another scene, Harvey gives the lead a book on French cuisine as a farewell gift, as of course, she is an aging celebrity, who is not relevant anymore, so cooking is something she could go back to as a retired woman.

The plot requiring the two bodies to switch every seven days means that there are always conditions on women’s freedom, choice, desires and work. Over exhaustion and leading disconnected dual lives juggling between the public and private are the heavy costs that capitalism demands from working women.

Similarly, the right to rest is a negotiation for women. Women workers and professionals are still negotiating there working hours, rest and recreation. Not all private offices are implementing unconditional paid maternity leaves in India; not all workplaces are ardently observing gender pay parity. If we borrow from theologian activist Tricia Hersey who founded the organisation the Nap Ministry, “rest” can be seen as a form of resistance. Contextually, her work defined “rest” as a counter-hegemonic political act by Black women against the discourse of slavery and racism (Hersey 2022).

The Substance could be seen as reflecting that “women are never at rest but always labouring.” The women, in absence of securities like paid menstrual leaves, or those women who are constantly working “on” their physical bodies, are never really resting, if one may put it that way. Industries like that of sex work, entertainment, modelling, etc. have women in the workforce but are usually heavily controlled by powerful men who own large shares of profits.

The feminine grotesque

As a satire on traditional body horror genre, The Substance also controls the narrative of the “feminine grotesque”, as in the final scenes, by allowing some screen space for it. The body is destroyed in the end but symbolically, in a glorious manner, doing exactly what the lead character had originally planned on schedule-wise. The destruction doesn’t happen with any hero v. anti-hero one-on-one tussle. Here, the woman’s body is the enactor as well as the subject. However, the feminine grotesque can be seen as a warning to the society of how distorted the outcomes could be if a woman constantly caters to the societal standards, expectations and is giving in to desperation.

Body horror has significant potential in putting it out rather assertively that there is violence and constant mutilation being done to the female body. It is done through a systematic psychological and physical oppression which requires a feminist inquiry even if the enactor is the woman herself. This elevates, to some extent, the conflicting discourse created by the liberal conception of “right to choice” or; that cosmetic enhancements done to a woman’s body by her is her right to choice and expression or; that there is no need to ask the problematic question if the choice is manufactured by the neoliberal industry using male gaze.

The Substance, thankfully, highlights that active choice could be manufactured. By the end of the film, as a takeaway, the audience is certain that the “monster” is the anomaly. The monster is the system, itself.

About the author(s)

Radhika Jagtap (jagtap.radhika7@gmail.com) teaches at the School of Law, University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Dehradun.