“As was often the case, you couldn’t tell whether abortion was banned because it was wrong or wrong because it was banned. People judged according to the law, they didn’t judge the law.“

These words resonate deeply when one thinks about the dark and complex history of women’s reproductive rights across the world. The agency of and over the female body has been snatched away by patriarchal legal systems time and again, even in the most advanced countries of the global West. This poses one significant question – does the law always get to be “above all?”

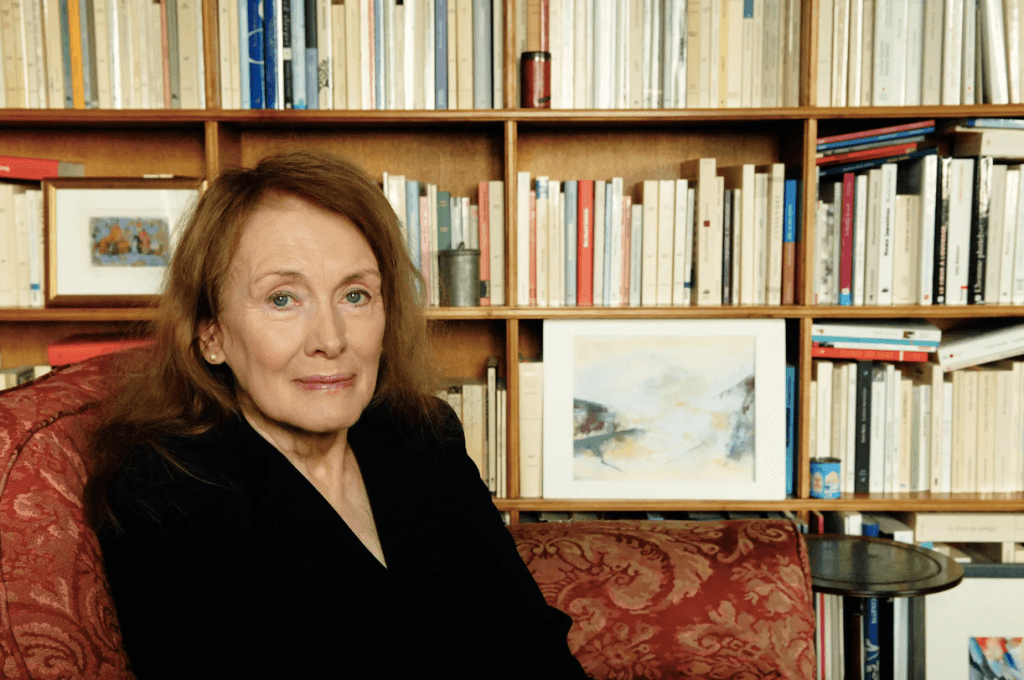

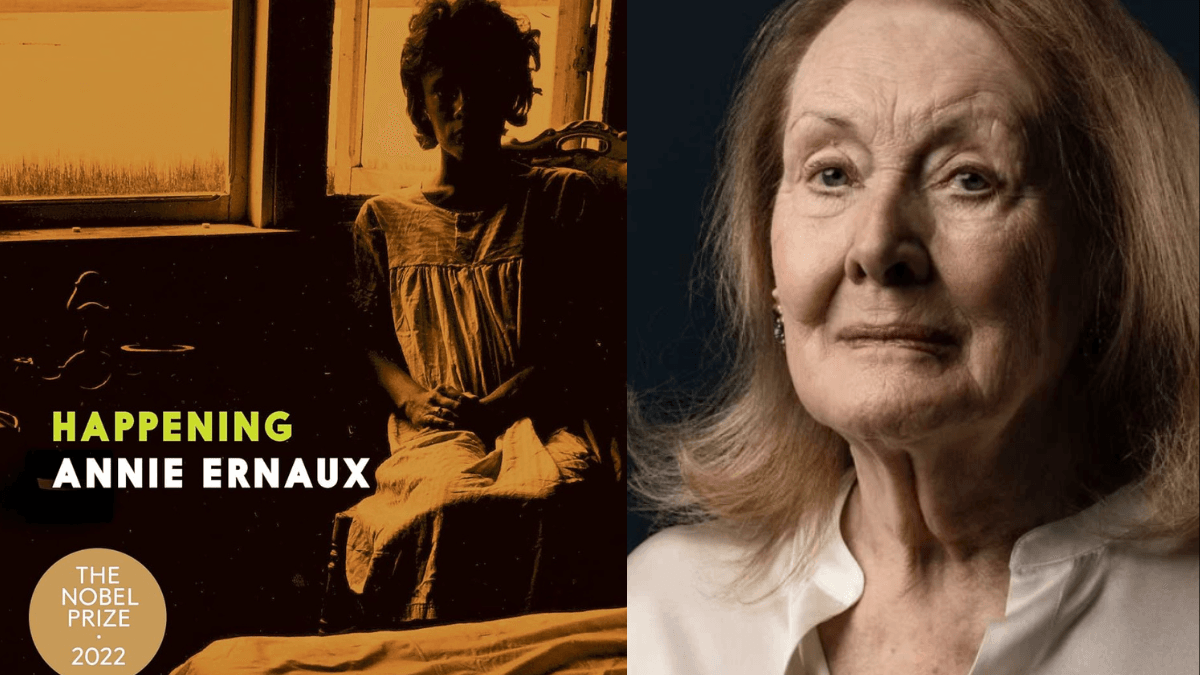

The issue of abortion is tightly woven into an intricate socio-cultural fabric of class, religion, morality and law. This fabric is minutely unstitched and examined in Annie Ernaux’s 2000 memoir, “Happening” in which the French writer narrates her deeply personal experience of seeking an illegal abortion in 1960s France. Through her memoir, Ernaux deals with the difficult task of writing from one’s memory – which inflicts immense psychological and emotional dilemmas, especially concerning traumatising experiences like this.

However, the writer emphasises the need to record the trials and tribulations of women under formerly enforced oppressive laws. As she says, “…when a new law abolishing discrimination is passed, former victims tend to remain silent on the grounds that “now it’s all over.” So what went on is surrounded by the same veil of secrecy as before.” Therefore, 60 long years since Ernaux’s travails, “Happening” remains both a window to the past and a mirror to the present– where anti-abortion laws and “pro-life” movements are not entirely separated from our reality.

Abortion, women, and gender injustice

The year was 1963, when Ernaux, a young and gifted student at a university in Rouen, France, found herself confronted with an unwanted pregnancy which disrupted her ambitions and plans for the future, and posed physical challenges. As she recalls in her memoir, her frustration and helplessness echoed the same of thousands of women across time and space who have found themselves in similar situations.

Unplanned pregnancies often disclose the harsh truth about the difference in the lived experiences of men and women, and how patriarchy rarely holds a man accountable for the consequences of their sexual encounters. It is only the woman, who is supposed to be “of good character” and assume utmost sincerity and responsibility as to how she regulates her own sexual life. As Ernaux mentions in her memoir, “The only person who failed to show an interest was the boy who had gotten me pregnant… I should have realised this meant he no longer cared and was anxious to resume his breezy lifestyle, concerned solely for his exams and future career.” Ernaux, meanwhile, being an ambitious researcher who planned to write a thesis on women in Surrealist writing, found herself incapable of working due to the physical and health issues arising during pregnancy. This is how gender inequality manifests itself through legal systems when it directly deprives a woman of the right to her own body, and the right to choose what she wants to do with her life.

Gender injustice backed by the law, also acquires a horrifyingly tangible form, through the physical pain inflicted on women by a state which does not even sanction the bare minimum – a legal abortion centre providing safe reproductive healthcare. Bound by the law which regarded abortion and contraceptives as punishable with terms of imprisonment, Ernaux recalls in “Happening,” how she turned to the illegal and unsafe options available to her. She started considering unsupervised, self-exercised abortions with knitting needles, and operations by underground, unqualified medical practitioners.

‘Pro-choice’ for all?

The mainstream ‘pro-choice‘ movement, as we know it today, does not shelter every woman equally. We realise how the issue of intersectionality is majorly ignored when we find that women from different social and economic sections – including low-income working-class groups, women of colour, and lesbian individuals – cannot identify with the movement at all. The movement’s singular focus on abortion rights often neglects class, sexuality, race, and other markers of difference.

In her memoir, Ernaux places a special emphasis on her economic identity and working-class background. Born into a family of labourers and storekeepers, she was a first-generation learner who turned out to be gifted and intelligent; thereby aiming for class mobility through her education. However, during this particularly difficult time of her life, Ernaux found herself in a strange middle-ground, living the dual life of an ordinary working-class woman and an educated Bourgeois, “modern” woman. In a particularly jarring episode that she narrates in her memoir, a medical intern verbally harassed and misbehaved with Ernaux the day she was hospitalised after aborting her foetus by herself.

However, later the intern seemed to be apologetic, only because he hadn’t known of Ernaux’s student background and had taken her for an ordinary salesgirl or factory worker. A nurse had later asked her why she didn’t tell the intern she was “like him” – a reaction that Ernaux describes in her memoir as the “assumption prevailing among “humble people” that “those in high places” enjoy the right to place themselves above the law.“

These subtle differences in the lived experiences of women belonging to different class backgrounds, despite being under the same oppressive regime, prove how intersectionality exists in the realm of abortion rights. In India, where abortion has been legal since 1971 with certain conditions, there remains a stark contrast between abortion services for the elite or middle-class urban population, and that for the underprivileged women in rural areas.

Skewed distribution of abortion facilities and providers, and underdeveloped clinics, continue to make abortion difficult in rural India. Even in facilities that do provide abortion services, there exist social obstacles like lack of confidentiality and insistence on the husband’s or relative’s consent, even though not required by the law.

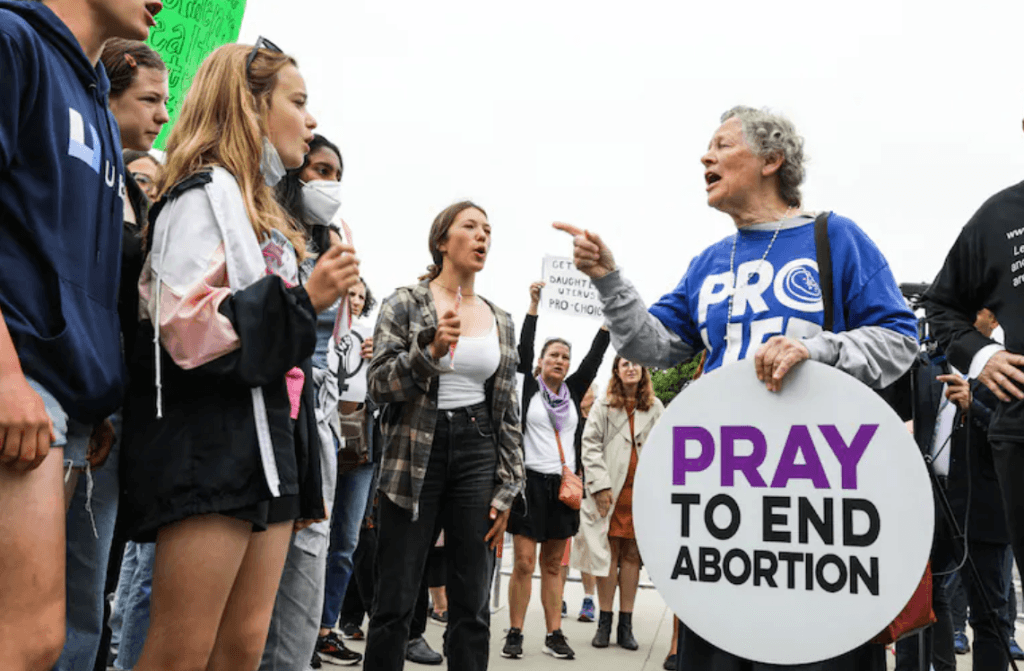

Religion and the right to life

Religion and the State are hardly separated when laws like that of anti-abortion are passed, with institutions like the Church fuelling legal restrictions constantly. In “Happening,” Ernaux recalls her interactions with the right-wing voters and devout churchgoers in her social circle, including her family physician Doctor V, who remained largely unsupportive of her decision. Religion’s moral necessity of preserving an unborn foetus’ ‘right to life,’ as well as the “sacred” duties of a woman as a mother and procreator, seems to present ethical conundrums. In her memoir, Ernaux also admits to being “through with religion” after confessing her abortion to a priest in a church one afternoon and immediately feeling like a criminal. In the eyes of a religious person like the priest, she was nothing but a sinner.

In this context, one might refer to contemporary American philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson, and her works on virtue ethics surrounding (and defending) abortion rights from a moral standpoint. In her famous 1971 essay “A Defense of Abortion,” Thomson presented a hypothetical scenario: you wake up one morning to find the body of a famous violinist attached to yours, who is sick and is using your kidneys with your rare blood type to survive. Is it morally incumbent on you to remain hooked up to the violinist, despite you not taking up the responsibility willingly? Through this cleverly engineered hypothesis, Professor Thomson demonstrates how the right to decline to aid someone, stays with the person aiding, considering that it is their body and they have the right to choose. It is not murder if you choose to detach the violinist’s body from your own. In other words, an unborn foetus’ ‘right to life‘ does not, and cannot, triumph over a woman’s right to decide what happens to her own body.

Similarly, a few years before this essay’s publication, Thomson’s British contemporary Philippa Foot, wrote “The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect” (1967). Here, Foot defined the Doctrine of Double Effect in abortion, in terms of the distinction between ‘direct‘ intention (what a person intends as the end goal) and ‘oblique‘ intention (what one obliquely intends as the action’s foreseen consequence). Given that Thomson formed many of her ideas on Foot’s theories, the direct intention in the violinist hypothesis would be the detachment of the violinist’s body for health and freedom – while the oblique intention would be the inevitable death of the violinist.

There have been several philosophical theories and discussions that defend abortion rights, tackling its difficult ethical dilemmas with logical, precise argumentation. Yet, even years of research and debate have not permanently eradicated the deeply-rooted stigma and conservative views when it comes to a woman getting an abortion.

In America, the ‘pro-life‘ movement has garnered a significant following among the masses, and even explicit backing from right-wing political groups. Since the US Supreme Court overturned Roe vs Wade (the 1973 case establishing the constitutional right to abortion) in 2022, abortion has been banned or limited in 18 American states. Thus, Ernaux’s experiences, as documented and narrated in “Happening,” remain largely relevant even six decades after its publication.

an amazing piece of article Meghma!

congratulations and keep it up dear friend.