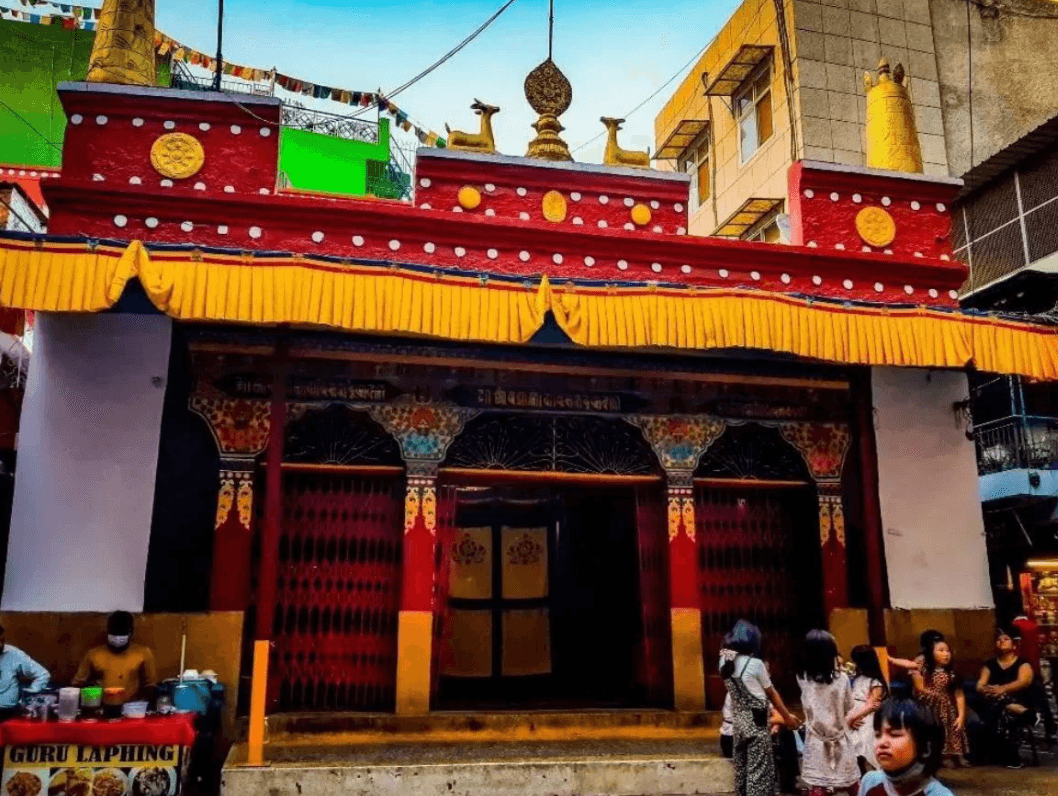

What was once a designated settlement for Tibetans marked by damp alleys and lines of people waiting to procure water from the pump has now transformed into a Tibetan cultural hub, with restaurants, hotels, shops and stalls run by Tibetan refugees, coexisting and carving a livelihood for themselves.

With the onset of the 1950s, the Dalai Lama, along with numerous Tibetan refugees were assured asylum by the Indian government, with the setting up of rehabilitation settlements for them in the country. According to the research article entitled, “Socio-Economic And Cultural Characteristics of Tibetan Migrants: A Case Study of New Aruna Nagar (Majnu Ka Tilla), Delhi,” the area comprises 12 blocks and about 350 registered families residing there.

The tale of the gradual development of Majnu Ka Tilla is the tale of the resilience and adaptability of Tibetans in a land that is away from home. In the words of Thubten Samphel in his book “Falling Through The Roof,” “Majnu Ka Tilla is a result of history’s injustice.”

Common beliefs and shared aspirations

Tenzin Wangdue, running a stall in the area, selling beads and objects regarded as sacred by Tibetans, while mentioning the little ways in which they keep their Tibetan culture alive through their entrepreneurial ventures, stated, ‘We like to believe that we have established a Little Lhasa here. Away from our homeland, we try to stay connected and integrated by decorating our stalls, shops and homes with Tibetan flags, which are regarded as auspicious, bringing good luck, and selling objects which symbolise our faith, like these beads. These are the only things we can hold on to, as reminders of who we are, and where we come from.’

When inquired about the presence of the Dalai Lama’s pictures on the doors of shops, he asserted, ‘He has been our guiding light. We hold him in deep respect and reverence. Little Lhasa cannot be complete without the presence (in spirit) of our leader.’

Commenting on the pertinence of the posters reading “Free Tibet” and “Students for a Free Tibet” often spotted on walls, Pema Lhamu, in conversation with FII, selling woollens at a stall, stated that ‘These are little things that convey our collective desire for an independent nation, free from the shackles of any hardship. It is one way of expressing our “we-feeling.” After all, our shared aspirations are what bind us together.’

Every year, Tibetans residing in the area ignite a protest to articulate their dissent against the Chinese occupation of Tibet, right outside the Chinese Embassy.

Another way by which Tibetans attempt to preserve their cultural symbols, shared meanings and practices is by selling Tibetan souvenirs, namely, little yak artefacts, beads bearing religious significance and handmade Tibetan jewellery. This attempt is also evident when one spots the symbol of the Nor Yak Café – the Tibetan yak.

According to the owner of a shop named NAMSA*, ‘Festivals are celebrated within the confines of the colony and in addition to Holi and Diwali, the Tibetan New Year (Losar) is celebrated with much excitement, also within the confines of the colony, followed by a visit to the monastery.’ This highlights how members of the community maintain a sense of in-group and belongingness, collectively celebrating festivals that integrate them. Further, he said, ‘MKT has also become a stopover for Buddhists travelling to visit the Dalai Lama.’

Interaction with cultures other than their own, while retaining one’s essence

Identities are multilayered and overlapping. They are never static, but ever-evolving. They come into contact with external influences which need not erode their essence but enhance them. When Dorjee, who sells hot dogs on a stall, was asked about decorating the stall with Tibetan flags while simultaneously selling the American hot dogs, he said ‘It is a way to do something different in the midst of the many cafés that are coming up, while simultaneously retaining a part of my identity.‘

Other signs of an interaction between the Tibetan entrepreneurs with non-Tibetan cultures can be seen in the form of Korean food items like kimchi being sold, in addition to Tibetan delicacies. This may be perceived as a way in which markers or Tibetan identity merge with aspects of cultures other than their own as a means to expand their ventures, attract more customers by appealing to their preferences, reflecting how their identity as Tibetans intertwines with their identity as entrepreneurs.

For Sanchi, a visitor, ‘It is very refreshing to see that the clothing showroom named Mapcha promotes its garments by employing Tibetan rather than Western models, which may be interpreted as one way of asserting Tibetan identity.’

On the other hand, Saloni, a pass out of Delhi University, who was visiting Majnu Ka Tilla with her friends after about 6 years, asserted, ‘The quaint cafés that are coming up may hamper the essence of the place as a primarily Tibetan hub. I cannot spot the woman who used to prepare laphing on a roadside stall. That space is now used up by a small stall selling kimchi and bibimpap. I do like how Lhasa Café’s board is carved out of Tibetan wood and ‘Welcome’ is written in both Tibetan and English.’

Thinley Dhondup, who owns the Norwang Café, describes its interior as an ‘amalgamation of Greek aesthetics and Tibetan essence. Drawing upon the white and blue shades of Santorini, we hope to appeal to the younger lot of the population. Our target audience is primarily college students and we hope to make the café appealing for them, serving Italian and Chinese meals, apart from Tibetan dishes.‘

A taste of Tibet

For X*, a woman entrepreneur selling Tibetan handicrafts, ‘These small business ventures in the market keep us connected to our culture since the items I sell have special significance in the Tibetan way of life.’ The woollen rugs she sells are handmade and give a taste of Tibetan craft. In her words, ‘What makes them special is that the wool was spun by hand and dyed using vegetable colours by women in the higher altitudes of Tibet in the days of the past. Women would weave a carpet for months to decorate their new home after getting married.’

When asked about the symbolism each colour in the Tibetan flag holds, she explained, ‘The colours symbolise elements of the earth and beyond – red signifies fire, white signifies the wind, yellow is the colour of the earth, green signifies water and blue signifies the space and the sky.‘

For Z*, ‘The area is a mini version of our homes. Even though the inner streets are dilapidated, and some walls are crumbling, there is no state-driven “revamping” of the market, it is still the hustle and bustle and little vibrant corners that give an essence of Tibet.’ The market for him can be compared to a living organism, with each stall and restaurant being the organs of the organism, working to contribute to the smooth functioning of the market.

New Aruna Nagar’s treasurer, Rinzin Wangmo expressed a desire for ‘better infrastructure in the colony as it is gradually transforming into a food hub. If the government is planning to initiate a development programme, it should actually deal with the issues faced on the ground, for instance, licensing, repairing the walls, and pavements, and beautifying the buildings. The concerned authorities have been requested from our end to restore our cultural essence.’

Cooperation and coexistence: way to go for Tibetans

Does the identity of Tibetan residents as entrepreneurs overpower their sense of belongingness as a community and the result is a declining social integration, or does it serve as another source of shared identity, not only as refugees but also as entrepreneurs?

One may assert that by running enterprises such as stalls, and restaurants within the market, the Tibetan refugees are characterised by a new form of solidarity, one that includes a degree of cooperation as well as competition, and adds another element to their sense of community feeling, wherein they may not have common experiences, but commonly shared values and beliefs in cultural traditions persist, binding the community together and at the same time, contributing to the functioning of the market.

It must be noted that the report does not aim to be either general, all-encompassing or exhaustive. It is imperative to acknowledge that the findings are relative are specific to a limited number of people for a specific time and are subject to change as time and contexts change.

*names have been changed to protect the identity

About the author(s)

Syeda Shua Zaidi is a student of B.A. (Hons) Sociology, at Miranda House. Passionate about poetry, filmmaking, heritage walks, social work and all things vintage, you would find her reading the works of Murakami, Khaled Hosseini and Agatha Christie while treating herself to a cup of tea. Firmly a believer of "disagreements are welcome, disrespect is not".