The British criminalised homosexuality in their colonies due to their belief in Victorian Christian puritanical ideas about sex. In India, this was done through the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which came into effect in 1862, including Section 377 that outlawed same-sex relationships.

This led to growing prejudice against the LGBTQ+ community, portraying them as criminals or kidnappers—a harmful stereotype still used to label homosexuality as strange or an illness. These biases have deeply impacted the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals, pushing them to the margins of society.

A study done by Careernet Prism highlights the struggles faced by LGBTQ+ employees in India, including sexual harassment, discrimination, and limited opportunities. It reveals that 25% earn less than they deserve based on their qualifications, and while 60% face harassment and 73% of them do not report it, often dismissing such incidents as minor.

A study done by Careernet Prism highlights the struggles faced by LGBTQ+ employees in India, including sexual harassment, discrimination, and limited opportunities.

In India, family plays a central role, and for LGBTQ+ individuals, gaining acceptance from their family is often the first hurdle. When they come out, families often view it as an illness and seek treatment. When this fails to bring change, families usually withdraw support. This lack of acceptance forces many LGBTQ+ individuals to leave their homes.

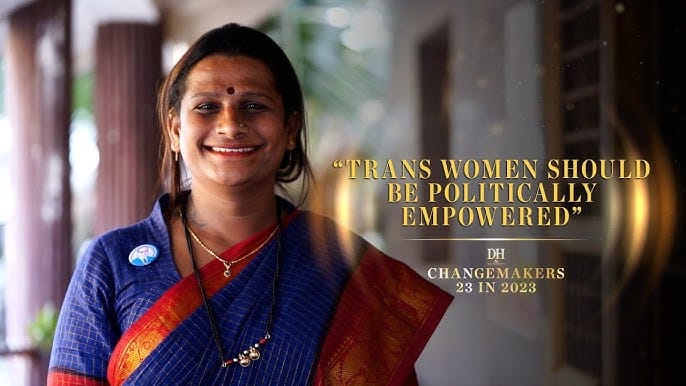

The same happened to Kaveri when she came out to her family as a transgender woman, she was forced to leave home at the age of 15. Kaveri D’Souza, who is from Cherkadi village in Udupi, Karnataka, now lives in Pethri with her family consisting of her brother, sister-in-law, and nephew and works as an auto driver at the Pethri auto stand and also takes calls from regular customers. Kaveri stands out as the first transgender woman auto driver in Karnataka, in a society where driving is seen as a male-dominated job and women are often mocked for being bad drivers.

She recalls how she had to drop out of school before completing class 10 because of the changes happening in her body and her struggle to identify with a gender different from the one assigned to her at birth.

From exile to empowerment: Kaveri’s fight against prejudices

After leaving her village in 2004 she slept at bus stands, worked at hotels, slept in her office because she did not have a space to go back. She did multiple odd jobs including working in the garment industry, selling churmuri outside weekly Yakshagana performances, begging, sex work, as an outreach worker for HIV/AIDS patients and with NGOs working with ransgender persons. During her time away from home, she met others from the LGBTQ+ community in Mysore and moved to Bangalore with them. They took care of her and provided her with a place to stay, but she was constantly worried if they would call her home to avoid trouble.

She lied and said she was from Kodagu in Coorg. She saved money and underwent gender affirming surgery, and decided to identify as Kaveri. Despite her desire to do something other than begging or sex work, she had no support. Later, she was offered a job as a D Group worker by M.P. JayaShree, but in 2013, she contracted tuberculosis, taking two years to recover. By the time she returned, the job was no longer available.

Uncertainty, lack of job security and uncomfortable living conditions made her start to think about returning home but it needed a great deal of emotional strength and courage.

Uncertainty, lack of job security and uncomfortable living conditions made her start to think about returning home but it needed a great deal of emotional strength and courage. She remembers the day she returned home, ‘In Brahmavara, there are not many transgender people. When I returned home, the whole village had gathered. Some people were crying, some accepted me, some others rejected me.’ But she was supported by her mother and some other villagers.

After her mother’s death, Kaveri returned to her village permanently and opened a grocery store. However, the COVID-19 pandemic hit just a month later, and after the second lockdown, she suffered heavy losses. She sent her resume to over 50 companies, but all rejected her solely because she is transgender. Kaveri often wonders what people think of transgender individuals. While living in Bangalore, she had learned to drive an auto-rickshaw from her neighbor, Kantaraj, an auto driver. At the time, she learned it out of interest, never imagining it would become her profession. However, this skill eventually paved the way for her to work as an auto driver.

Building a future, Kaveri’s dreams beyond the auto rickshaw

Kaveri met Prasanna Bhat, a member of the Samruddhi Mahila Mandali from Annapoorna Nursery, who was impressed by her determination. The organisation helped Kaveri by giving her a small amount of money to buy an auto rickshaw. Deepa Bhandari, a member of the Inner Wheel Club in Udupi, a women’s charity group, praised Kaveri’s strong will. She recalled that ‘After an event that promoted women learning to drive and earn an additional stream of income, Kaveri was the only one to approach us. Even during the loan process, her determination was evident.’

Although Kaveri had learned to drive an auto years ago, she faced challenges in getting her license due to a lack of identity proof. But after she owned the auto nothing could hold her back, she describes it as ‘a sense of freedom and independence that comes with owning a business.’

Later, with the help of Prasanna Bhat, she connected with Roshan Belman, the founder of Humanity Trust Belman, who assisted in clearing her loan of ₹1,70,000 for the auto.

Later, with the help of Prasanna Bhat, she connected with Roshan Belman, the founder of Humanity Trust Belman, who assisted in clearing her loan of ₹1,70,000 for the auto. The donors of Humanity Trust are also supporting Kaveri in completing the house she has been slowly building for 10 years with limited funds. The Trust is covering the remaining construction costs. Alongside owning her own home, Kaveri’s other big dream is to raise a child, and she is now planning to adopt a child.

Hard work and fight for dignity and acceptance

In the time span of a year and nine months, Kaveri has built a loyal customer base. Gulabi, a resident of Kaveri’s village, shares that Kaveri is different from other drivers; she treats people with respect and makes them feel like family. Throughout her journey, Kaveri met many people, some supportive, others discouraging since many still view auto driving as a “male profession.”

However, she is bravely challenging these gender-based work divisions. As a transgender woman, it takes even more courage, as society is not ready to change its conservative views towards them. They are more likely to be attacked, objectified and harassed by males. By driving an auto rickshaw, Kaveri not only hopes to change her life but also aims to live with dignity and aspire to get acceptance into mainstream society.

Kaveri expressed her concerns about the lack of awareness within her community and stressed the importance of increasing awareness about the facilities available to them, as well as the self-employment schemes introduced by the government for the transgender community.

While talking about conditions of other transgender persons, she says ‘People like to compare my way of living with those of my community members. I wanted to live a life outside of begging and sex work. This was possible because my family accepted me and provided me with moral support and a place to live.’ For many transgender individuals, social conditions may not provide the opportunity for such an outcome.

Kaveri’s role in changing society’s views on transgender individuals

Rupa Hasan, a writer who works along with sex workers and transgender individuals, explains that Kaveri’s work, which is public and involves frequent interactions with others, is significant because it challenges people to face their own biases. According to Rupa ‘The general perception is that transgender people only make a living through begging and sex work. A lot of people attribute stigma to their jobs and identities.’ The reality is that it is their vulnerabilities that force them to turn towards being exploited.

Rupa Hasan, a writer who works along with sex workers and transgender individuals, explains that Kaveri’s work, which is public and involves frequent interactions with others, is significant because it challenges people to face their own biases.

She further says ‘Seeing Kaveri hard at work in a profession where even cisgendered women are rare, people will have no excuse but to reexamine why they hold such prejudice.’

Kaveri, through her courage, is actively challenging the patriarchal norms of society, pushing against the traditional boundaries that have limited many people like her. By taking bold steps in her profession and life, she is not only defying societal expectations but also moving society forward, one step at a time, toward greater inclusivity. Her actions challenge the existing status quo and inspire others to embrace diversity, helping create a more accepting and equal society for all, regardless of gender.