In a tight-knit yard in Kannur, Kerala, Bindu chechi slips a silver spoon into a crystal jar of mango pickles. ‘This dish,’ she says with a twinkle in her eye, ‘got my son his first ever bike.’ Ten years ago, she, like any other woman of her age, was a homemaker with a deep understanding of spices and flavours that had been preserved over time. Now, she is a part of a coterie of twenty women whose tangy enterprise moves across state lines. Her tale is one of the many stories where a small pickle jar has evolved from an everyday item into an unexpected tool for financial freedom.

This transformation of pickles from a table fare to a sales driver spotlights one of Kerala’s most remarkable yet underappreciated turnarounds. By leveraging the intersections between commerce and heritage, a host of women are creating lucrative businesses out of ethnic cuisines. Such pickles, brewed in pots and packed in jars, hold inside not only the distinct hint of mangoes or the burst of lime, but the chronicles of female fortitude, grit, and a thorough rethinking of their identities in the social landscape of our times.

Despite a significant amount of research on Kerala’s political participation rate and increasing literacy rates, the micro-economy of pickle-making offers a unique perspective on female emancipation, infused with elements of karuveppilai, masala, and self-sufficiency.

More importantly, the art of pickle-making is not confined to preserving food; it is about preserving the promise of a better and brighter tomorrow. In a place where coconut trees and ships flank the coastline, each and every jar of pickles cradles both time-honoured traditions and the dignity of individuals while simultaneously embracing modern markets.

From roots to revenue

The culinary timeline of pickling practices in Kerala is deeply entwined with its legacy of maritime trade and the prevalent cultural practices of the day. The communities in Kerala had mastered the art of food preservation through oil-sourced fermentation methods long before Vasco da Gama’s desire for Indian spices.

Originating from the Persian language, the Malayalam term “achaar” (or pickles) connotes a mix of intercultural interactions in the genesis of Kerala’s pickling traditions. Alluding to the seasonal changes happening in a year, the kitchens in Kerala’s traditional households store different varieties of pickles: gooseberries during winter, mangoes in summer, and lemons all twelve months.

The art of pickle-making, therefore, remained as a silent whisper of traditional knowledge, a part of the unpaid work women carried out for the well-being of their families.

Since the Indian subcontinent rests in a tropical climate, pickle-making became a necessity to slow the spoilage of edibles in a dynamic weather. Moreover, a key development in the unfolding of this history has a lot to do with how pickle-making exemplified a niche area where women were at the helm both in terms of techniques and insights. Strangled amidst a culture of restrictions, the requisite set of knowledge needed for effective pickle-making—interpreting time-of-the-year differences, fine-tuning the fermentation formula, and upkeeping the shell life quality—paved the way for an increased association of women with the recipe of pickles.

Despite their value, the significance of these skills was always trapped in the domestic bubble. Their rigorous toil, unrelenting commitment, and intuitive grasp needed in pickle production were rarely assessed in economic terms. The art of pickle-making, therefore, remained as a silent whisper of traditional knowledge, a part of the unpaid work women carried out for the well-being of their families. In the present time, this established practice of pickling is taking a new form as modern women entrepreneurs are now capitalising on this vast body of inherited wisdom to bring cultural riches to the marketplace.

The collaborative revolution

In 1991, the Indian government introduced the economic policy of liberalisation, privatisation, and globalisation to open up the corridors of India to the global market. These reforms liberalised trade, minimised government intervention, and encouraged entrepreneurship. In the same decade, in 1997, vying for similar economic transformation, the State Poverty Eradication Mission (SPEM) of the government of Kerala introduced an initiative called Kudumbashree—a poverty eradication and women empowerment program aimed at microentrepreneurship.

Conceived as a three-tier framework, it established Neighbourhood Groups (NHGs) with 10 to 20 members, where eligible women can enrol themselves as members.

Through this tripartite model, Kudumbashree quickly realised that women did not require a new set of skills, but rather they only needed assistance in monetising their existing skillset. Instead of forcing unfamiliar strategies, it grounded itself on their established field of knowledge, where pickling initiatives flourished spontaneously within the model. What they lacked, however, was support in marketing and sales, and Kudumbashree met those needs perfectly.

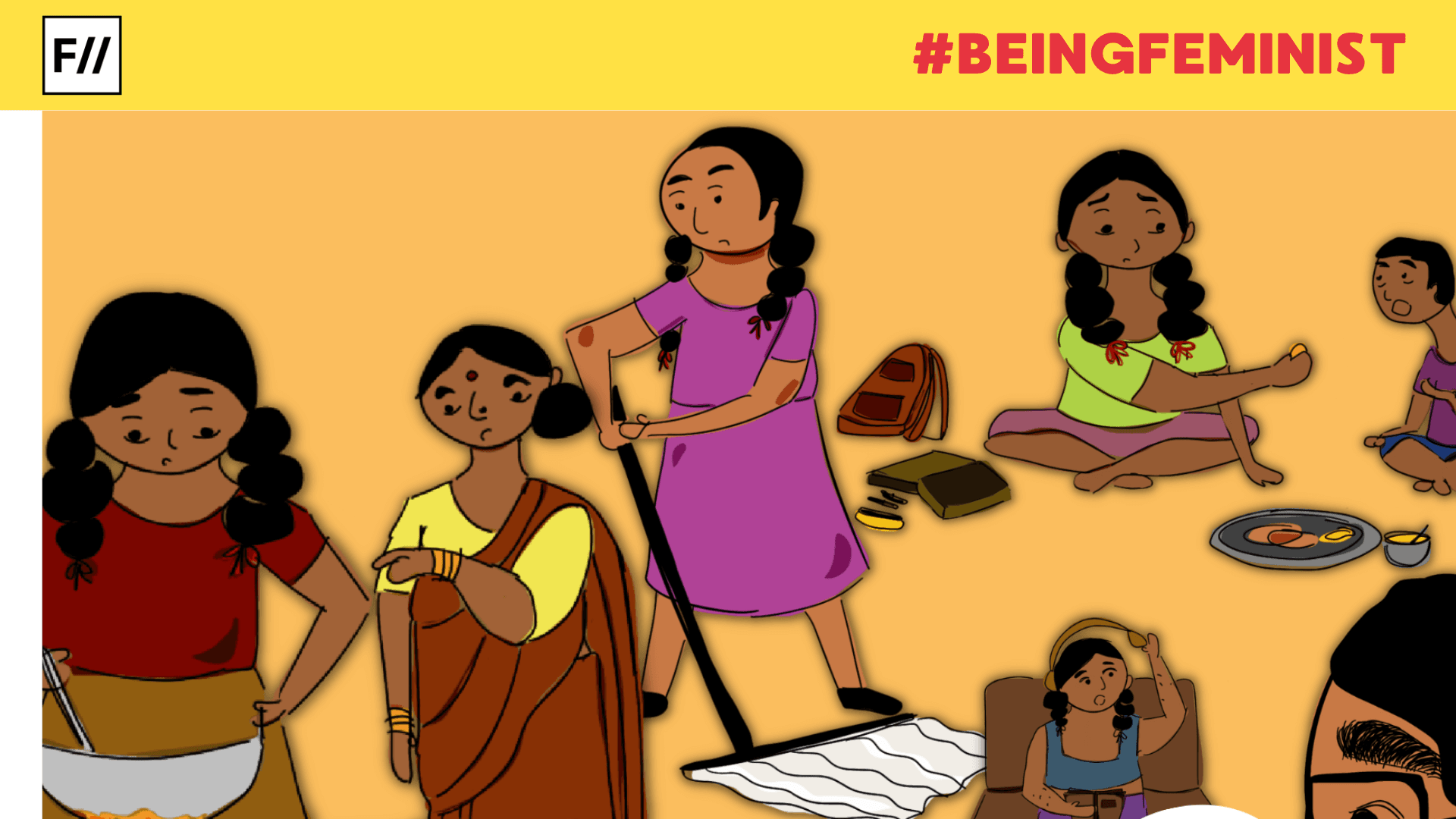

In the complexities of Kerala’s social stratification, where entrenched gender roles perpetuate inequality, the very act of making pickles developed into a credible venue for women’s participation in the workforce. These micro-scale enterprises navigated cultural boundaries and innovated within established traditions.

Through this, women afforded the opportunity to engage in remote work while also trying to increase their sphere of influence. This level of fluidity is essential in a society where women are often relegated to the background even when there is an incessant desire to carve out a space for themselves. By harnessing the power of pickling, these women effortlessly merged financial pursuits without upsetting any of their other activities in daily life. This flexible work arrangement mirrors what sociologist Saskia Sassen explains as the “informal economy“—a forum for the oppressed groups to connect, collaborate, and partake in a post-formal economic system.

By facilitating professional development workshops and monetary aid, Kudumbashree equips these women with commercial acumen, linking them with vendors, suppliers, and consumer groups in the surrounding areas. This allows the newly empowered women, particularly those from the under-represented social groups, to escape financial vulnerability and exclusion. While economic prosperity is the most significant outcome of this transformation, it also kindled a sense of agency and self-efficacy. When women see their products in stores, they feel acknowledged and valued. As a result, they slowly start to break the mould of “only doing chores” to actively seek provider roles and financial responsibilities. In a way, the mere act of pickle-making is wrestling with the relics of systemic oppression to clap back against it.

More importantly, the economic viability of these community-aided pickle-making ventures owes its success to the pluralistic landscape of Kerala society. As the state holds a significant chunk of the expatriate community in Gulf countries, the demand for these home-based pickles surged. The sentimental value attached to these outlets catered to the diaspora, and it gave them an edge over, at least, some industrial producers. While these ventures profited from a modest rise, it lit the fuse for a feminist revolution. Soon the networking and camaraderie of these women enterprises created a space for themselves where they could assert their individuality even amidst a collective.

Several women are now part of collaborative organisations from where they could, if needed, lift each other up, promoting reciprocal support and social solidarity. This collective, thus, fosters an environment through which women can embrace novel responsibilities and forge their newfound autonomy. These networks, therefore, carry unparalleled gravity as they enable women to thrive in the fast-paced world of entrepreneurship without relinquishing their culture and community. As the pickle makers of Kerala join to light the way forward, they are reconciling tradition with progress.

All in all, in Kerala, the humble jar of pickles is now transcending its essence to represent new vistas of social mobility. In the warmth of female solidarity, the process of pickle-making has evolved as a beacon of hope, freedom, and resistance. It highlights the ways in which these enterprises stand as a testament to the power of indigenous knowledge in combating patriarchy. Through their steady engagement with entrepreneurship, women are constantly negotiating their place in the public sphere, redrawing the lines of “acceptable” employment for women.

In a way, pickling is a metaphor of agency and change, a place where flavours of culture and ommerce blend. Hence, while acknowledging the savoury delight of Kerala’s pickles, let us not lose sight of the women who made this possible. Their tales, embedded into the heart of every jar of pickle, whisper stories of unbroken spirits and unshakeable resolve. Overall, in the citrussy bite of these pickles, we discover the taste of liberty—of a flavour that promises the hope of a radiant destiny.

About the author(s)

Akhila holds a Masters' degree in Society and Culture from IIT Gandhinagar. With a passion for exploring ideas through words, she enjoys writing and reading, often diving into books and essays that challenge perspectives. When not immersed in her academic or creative pursuits, she finds joy in watching movies and engaging in thoughtful conversations.