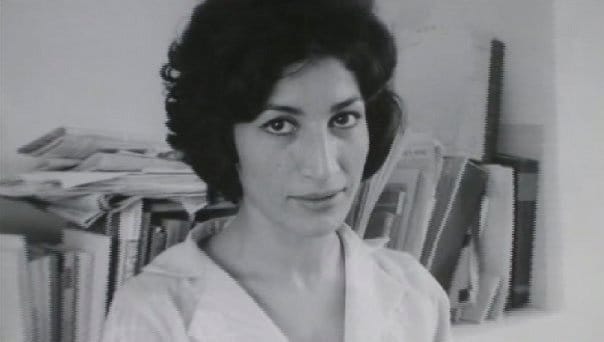

When it comes to the history of modern Iranian culture, there are only a few who shine as brightly—and as tragically—as Forough Farrokhzad. A poet, author, and filmmaker, Farrokhzad was a woman who defied the traditions of her time to carve out a legacy that has inspired millions after her. Her life, though brief, was one of passion and rebellion against the patriarchal forces that incessantly aimed to enslave her freedom.

Her artform was an unapologetic and personal rebellion against the deep-rooted patriarchal traditions of her country. In a letter dated January 2, 1956, Farrokhzad wrote, “My wish is for Iranian women to be free and equal to men. I am fully aware that my sisters in this country suffer from men’s injustices, and I use half of my art to articulate their pain and anguish.” But her artform also exacted a huge price from her—having been ostracised by her family, losing custody of her only child, and receiving heavy criticism from contemporary literary giants. After all, a woman who thinks, a woman who expresses, and a woman who writes is dangerous. How could a woman be allowed to make a space for herself in an arena largely dominated by man?

In the afterword to her first poetry collection, “Captive,” Farrokhzad wrote, “Perhaps because no woman before me took steps toward breaking the shackles binding women’s hands and feet and because I am the first to do so, they have made such a controversy out of me.”

Early life of Forough Farrokhzad

Born on January 5, 1935, in Tehran, Forough Farrokhzad was the third of seven children in a conservative middle-class family. Her father was a strict military officer who instilled discipline in all of his children. Her love for literature began early, ignited by Persian poetry and the works of Rumi and other Persian poets.

Farrokhzad married at the tender age of 16 to Parviz Shapour, a satirist and cartoonist, against the approval of both their families. While the marriage gave her a son, Kamyar, it quickly became a suffocating arrangement for Forough. She wrote about her feelings in the 1955 poem “Captive“:

I think about it and yet I know

I’ll never be able to leave this cage

Even if the warden should let me go

I’ve lost the strength to fly away.

Three years into the marriage, by 1954, the couple divorced—a scandalous move in conservative Iranian society where a divorced woman was looked down upon. The divorce resulted in her losing custody of her son—a heartbreak that would eventually haunt her life and poetry.

Forough Farrokhzad: The rebel poet

Farrokhzad’s first poetry collection, Captive, was published in 1955, laying bare her personal struggles and desires. Its boldness about female sexuality and emotional vulnerability caused a stir in Iranian literary circles. Unlike many poets of her time, Farrokhzad didn’t hide behind metaphors, but rather her words were raw, piercing, and unabashedly honest.

Erotic poetry was commonplace in Persian literature. But what was not acceptable was a woman writing about such affairs. And to add to that, here was a woman who wasn’t just writing about her sexual desires but was also recounting her affair with a man who was not her husband

The twelve-line poem “Sin” explicitly detailed her affair in 1954 with Nasser Khodayar, the editor in chief of Roshanfekr, a reputed literary magazine in Iran.

“I sinned a sin full of pleasure,

In an embrace which was warm and fiery.

I sinned surrounded by arms

that were hot and avenging and iron.“

Erotic poetry was commonplace in Persian literature. But what was not acceptable was a woman writing about such affairs. And to add to that, here was a woman who wasn’t just writing about her sexual desires but was also recounting her affair with a man who was not her husband. This infamous poem exposed her to much ridicule and controversy among the literary circles and common masses of Iran.

She further writes:

“In that dark and silent seclusion,

I sat dishevelled at his side.

his lips poured passion on my lips,

I escaped from the sorrow of my crazed heart.“

The use of evocative language and explicit sensual imagery stirred unimaginable controversy but, at the same time, cemented her as a bold woman who was not afraid to lay bare her erotic desires on paper. In the poem, Farrokhzad is an active participant in the act. It reversed centuries of Persian literary practice. In Iran, men could talk about lovers as they please, but a woman who did so was considered to have committed a transgression.

Her later collections, including The Wall (Divar) and Rebellion (Esian), reflected a maturing poet who questioned societal norms, gender roles, and her own place in the world. Her poems essentially called for women to rise up against years of oppression and injustice. She made men the subjects of her desire while owning her own sexuality.

Forough’s poetry, mostly written in free verse, broke away from the classical forms of Persian literature. In doing so, she, in her own capacity, modernised the art form. But she invited much ridicule from the puritans in the literary circles who believed in the sacrosanctity of classical Persian poetry.

One of my most cherished poems by her is Another Birth. She reflects on philosophical questions about life and death with such beautiful imagery and frankness that only a few can achieve.

She writes:

“Maybe life

is a long street in which every day a woman with a basket passes by

Maybe life

is a rope with which a man hangs himself from a branch

Maybe life is a young child coming home from school

Maybe life is lighting a cigarette in the languid pause between making

love and making love again

or the distracted gait of a passer-by

who lifts his hat from his head

and with a meaningless smile says to another passer-by, Good morning“

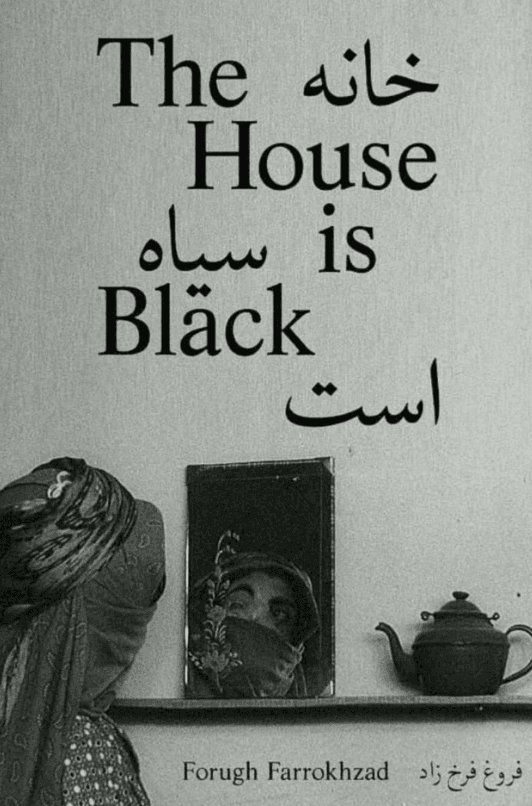

The House is Black: Her directorial venture

Farrokhzad’s genius wasn’t confined to poetry. In 1962, she directed The House is Black, a short documentary about life in a leper colony in Tabriz County. This film, produced under the guidance of her lover and studio owner, Ebrahim Golestan, is considered a cornerstone of Iranian cinema.

The documentary was produced in the twelve days that she lived in the leper colony. The film masterfully shows imagery of suffering with lyrical narration by Farrozkhad as she reads her poetry, creating an emotional and thought-provoking experience. Farrokhzad’s genius shines through in every frame, turning what could have been a voyeuristic portrayal into a deeply intimate work. One can argue that the stark portrayal of entrapment and monotony in the film is almost a reflection of her own life and also of Iranian society.

Though it was her only film, The House is Black cemented her status as a pioneering filmmaker. The film won the 1963 grand prize for documentary at the Oberhausen Film Festival in West Germany. It is considered to be a cornerstone of the Iranian New Wave.

Influence in Iran’s cultural landscape

To understand Farrokhzad’s significance, it’s essential to consider the Iran she lived in. Farrokhzad was active in a time when Iranian society was going through a tug-of-war between modernisation and tradition under the rule of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. Traditional values clashed with Western influences, creating a tense atmosphere for anyone challenging societal norms. Farrokhzad thus became a symbol of this cultural crossroads.

This can be seen in her poetry as well. While her influences were majorly Persian classical poets like Rumi, she managed to blend them seamlessly with modern forms of poetry. Talking about her poetry, Iranian poet Fatemeh Shams said, “She always had one eye back on tradition and one eye toward the future.”

But Iranian society was unforgiving. Farrokhzad’s bold life made her the target of controversy and judgement. With her progressive ideas and feminist themes, she became a cultural symbol of resistance and freedom.

A Cultural and political icon

Forough Farrokhzad’s influence extended beyond poetry. Her influence seeped into the lives of millions who were subjected to the relentless oppression of orthodox patriarchal forces. She became a cultural icon for those who dared to challenge the status quo. Her works mostly came to the forefront in 2022 during the Mahsa Amini protests.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, her works were banned in Iran for over a decade. Despite this, her poetry continued to circulate underground among feminist circles and cultural rebels. In many ways, Farrokhzad became a symbol of resistance for all those who dared to defy Iran’s oppressive establishment.

Farrokhzad’s legacy beyond life and death

Farrozkhzad was a woman ahead of her time, unafraid to challenge the norms of her society and express her truth through her art. Farrokhzad’s life tragically ended on February 14, 1967, in a car accident at the age of 32 while returning from lunch at her mother’s house. Her death left an unfillable void in Iranian culture, and hundreds of people attended her funeral.

Farrokhzad is often called the Persian Sylvia Plath, as they were both similar in their poetic style, era, and untimely death. Both women were pioneers of feminist literature and have left behind a body of work that still continues to be studied and influence millions.

Despite existing over half a century ago, her legacy endures. Today, she is celebrated not just as a poet but as a woman who dared to live her life on her own terms despite the challenges that society put her through.