I’m in fifth grade, and my family includes three women: my grandmother, my mother, and my older sister. But, yes, my mother is the most beautiful of us all. She wears vermilion in her hairline, a bindi on her forehead, a mangalsutra on her neck, heavy bangles on her wrists, gold rings on her fingers, and colourful sarees that look great on her. Her anklets tinkle when she moves, and she wears toe rings in two of her toes.

My sister and I, two little girls, have no idea why they look so different. All I know is that my mother’s vibrant outfits and ornaments make her appear beautiful, and I want to look like her.

My grandma, however, is different. She always wears a basic white sari with little floral patterns and just a pair of kadas around her wrists. My sister and I, two little girls, have no idea why they look so different. All I know is that my mother’s vibrant outfits and ornaments make her appear beautiful, and I want to look like her.

Here’s a little secret, when no one is watching, I sneak into her room. I look for a dupatta and wrap it around myself like a saree, hoping to resemble how my mother wears hers. I put on her bangles, which are big for my wrists, and wrap a thread around my neck, imagining it is a mangalsutra. I stand in front of the mirror, hoping that I appear as beautiful as she does. But I don’t always get away with it. When my grandmother catches me, she criticises me, claiming that only grown-up, married women dress like that. She claims I am too young. But I don’t care; I dream of the day when I’ll be grown up, married, and as beautiful as my mother.

Time passes, and I am now in eighth grade. I noticed little changes in my mother. Her vibrant sarees have been replaced with plain suits, her bangles are fewer, and her hefty anklets have been reduced to a single silver chain around her ankle. My grandmother observes as well, and she dislikes it. She warns my mother, stating, ‘A married woman should dress appropriately. Where’s your jewellery? Your bangles?‘

One night, I see my mother quietly working in the kitchen, outfitted in a plain nightgown with her hands bare. Then my grandmother steps in, frowning. ‘A married woman should look like one,‘ she adds forcefully. ‘Suhagan ke gehne hi uski asli pehchan hote hain.’ It almost feels like she’s attempting to mimic Deepika Padukone’s iconic phrase from Om Shanti Om, ‘Ek chutki sindoor… suhagan ke sir ka taj hota hai. Ek chutki sindoor, har aurat ka khwab hota hai.‘

My mother listens silently, saying nothing. I wonder how many times she’s heard this and simply stood there, taking it all in. And I think to myself—one day, when I’m older, maybe I’ll understand all this.

Now I’m in the present, and that was my story, much like the opening scenes of a film, when the narrator discusses the past while revealing how those experiences impacted the present. And now I understand why my mother gradually stopped dressing up and remained silent over my grandmother’s scoldings. I believe she was simply tired of being instructed how to look and act every day, of not having the choice to pick her own looks, and of spending her entire life trying to become the “perfect bahu,” or ideal suhagan. However, though my grandmother passed away years ago, my mother still follows all of her “rules.” Every single one.

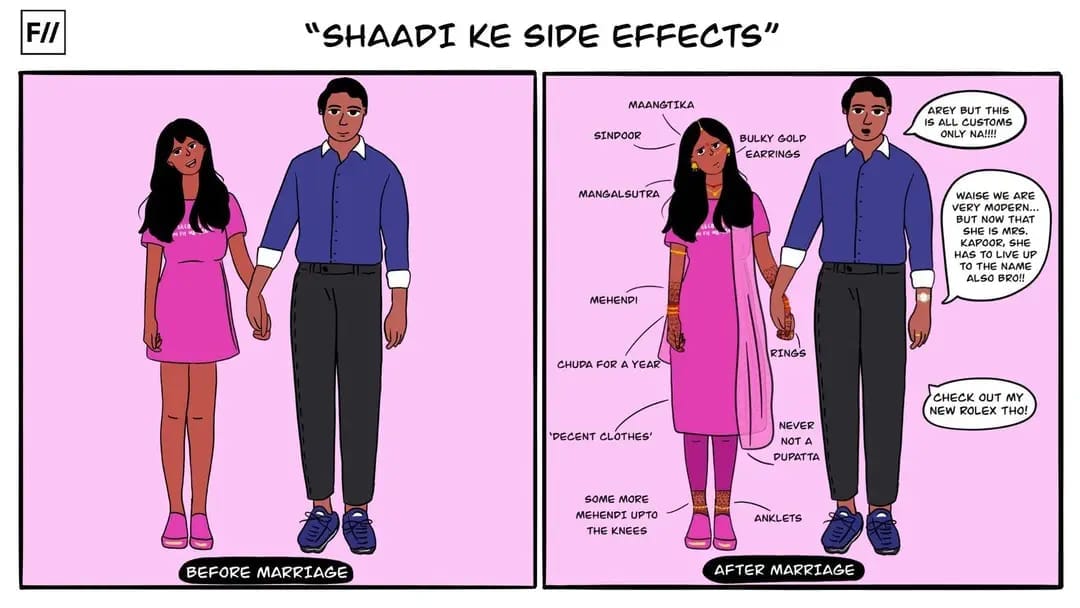

I don’t understand why being a married woman should be defined by your in-laws’ expectations or society’s set of ideals.

They say, ‘Never say never,’ yet here I am, saying it anyway. Don’t judge me, but I don’t see myself becoming like my mother. I don’t understand why being a married woman should be defined by your in-laws’ expectations or society’s set of ideals. My identity should not be limited by someone else’s perception of how a married woman should appear or act.

However, life gave me an unexpected twist. My sister, who has just been married for a year, has become a version of my mother. It’s just heartbreaking, but because it’s her story to tell, I won’t go into detail. Nonetheless, witnessing her transform into my mother 2.0 and attempt desperately to please her in-laws by transforming herself left me shocked and a bit concerned.

Moreover, just lately, during Karwa Chauth, I saw another aspect of it. Through social media, I witnessed some women enthusiastically posting their whole solah shringar, others opting for simplicity and attending the rituals in casual clothing, and some who, despite their own preferences, dressed up as suhagan to fulfil family expectations.

It helped me recognise that my perspective should be one of support for the right to choose rather than against marital symbols. ‘It’s about having the freedom to choose,‘ I thought to myself. This is not only my story; it is the story of countless women who need to find a balance between tradition and identity. So I reached out to a few women to learn about their thoughts on marital symbols, known as “suhag ki nishaniyaan“—and whether they feel empowered or pushed by them. This is what they had to say.

What women love wearing as married women, and what they don’t

These women, aged between 27 and 40, navigating married life in different states and fields, come from diverse backgrounds. However, about 75 percent of them have witnessed their mothers sacrifice their personal style and lifestyle to meet societal and in-law expectations. As a result, when it came to their own marriages, they were determined not to lose their identity to fit in.

Niharika Vats, a 30-year-old digital marketer, shares, ‘I wear my toe rings and a bracelet on an everyday basis. Wearing bangles, bindis, and other marital symbols every day would feel like a burden to me.‘

Niharika Vats, a 30-year-old digital marketer, shares, ‘I wear my toe rings and a bracelet on an everyday basis. Wearing bangles, bindis, and other marital symbols every day would feel like a burden to me.‘ Pragati Gupta, 27, who works in the finance department, explains, ‘After my marriage in 2021, I did wear mangalsutra and sindoor for a few weeks, but it wasn’t out of any obligation. It was mostly to respect the traditions of the family I was joining. These symbols represent a woman’s marital status, and after that I didn’t wear any of these symbols except my engagement ring, which, of course, is very meaningful and special to me. I believe it should be a personal choice.‘

Mandeep Panesar, a 32-year-old housewife, shares, ‘I wear traditional symbols occasionally, mostly when I go to parties or weddings to look more beautiful. Personally, I respect these symbols, but I prefer staying comfortable at home.‘

Harman, a 30-year-old Ph.D. scholar, adds, ‘I love wearing bindis every day for my own happiness—it has nothing to do with being married to me. I rarely wear other traditional marital symbols. I don’t like the social concept of a woman needing to wear these symbols to prove her marriage.‘

Meenakshi, a 33-year-old media manager, says, ‘I don’t wear any of these symbols regularly; the bindi has always been a part of my personality, even before marriage. I wear it daily as part of my outfit. On special occasions like Diwali or other festivals, I do wear mangalsutra or sindoor, but that’s purely my choice. No one pressures me, and my husband and in-laws respect that.’

Deepika, a 42-year-old associate professor, wears traditional symbols for their positive energy. ‘I wear them regularly, as traditionally they are believed to hold positive energy. I also wear bichua and payal, as they have health benefits.‘

Deepika, a 42-year-old associate professor, wears traditional symbols for their positive energy. ‘I wear them regularly, as traditionally they are believed to hold positive energy. I also wear bichua and payal, as they have health benefits.‘ Similarly, for Rekha Singh, a 33-year-old central government employee, traditional norms hold significant value. ‘I wear traditional symbols every day. They hold personal significance, and I believe traditional norms should be followed.’

Overall, when asked if they’d still wear traditional symbols if given the choice, 75% of women said they would like to avoid it, while 25% expressed they would wear them due to strong beliefs and attachments.

When your choice affects your relationship, how do you draw the line?

For many women, the balance between personal choices and family expectations can be tricky, especially when it comes to dressing or behaving in ways that are deemed traditional or acceptable by society. Niharika shares her experience: ‘Neither my partner nor my in-laws believe in the idea of dressing up to look a certain way. However, the community or society is often quick to remind me that I’m married and should look the part.’ She further adds, ‘As a wife, I’ve always made sure to maintain a relationship of equality with my partner and not treat him like a ‘pati parmeshwar’ as society expects.‘

Pragati also talks about societal pressures. ‘I have never felt the need to behave or dress in a certain way to maintain harmony within my family. However, on occasion, you do come across judgement from the community, which I think is quite common in our country where it is expected for certain social norms to dictate specific behaviours or lifestyles.’

Mandeep shares how sometimes these social norms add pressure on her relationship with her husband, ‘My husband is okay with my dressing till my in-laws are okay. If he feels that his parents, relatives, or society will question my dressing, he also will feel uncomfortable. And that’s why I agree with the statement that dressing or behaving traditionally is necessary to maintain harmony in the family.’

Harman on the other hand, not only feels the pressure of societal expectations but acknowledges how exhausting it is, ‘Yes, it definitely is in our society. But it all is exhausting. Obviously, anybody not following traditional norms would be seen and perceived badly in the community.’

Meenakshioffers a more conciliatory approach. ‘I think if your family is respecting your choices and views, then you should also be kind to them and try to indulge in something or some rituals if it gives them happiness for a while. I mean, it takes two to dance. Right?‘

Meenakshi offers a more conciliatory approach. ‘I think if your family is respecting your choices and views, then you should also be kind to them and try to indulge in something or some rituals if it gives them happiness for a while. I mean, it takes two to dance. Right?‘ She emphasises the importance of drawing boundaries early on in relationships: ‘I always made my choices clear since the beginning of my marriage so that nobody expects things out of me that I do not like.‘

As a feminist who wanted to know when these symbols represent real identity vs the urge to fit in, it’s satisfying to witness these women cross the line between society’s image of the “perfect married woman” and their authentic self. Sure, expectations persist, but they understand that the option is theirs, honour tradition or redefine it.