Warning: spoilers ahead

Putting it briefly, Shuggie Bain is a book about alcoholism, queerness and Thatcherism. Most of all, it is about love, and despite the love not being healthy at all times, it is always pure.

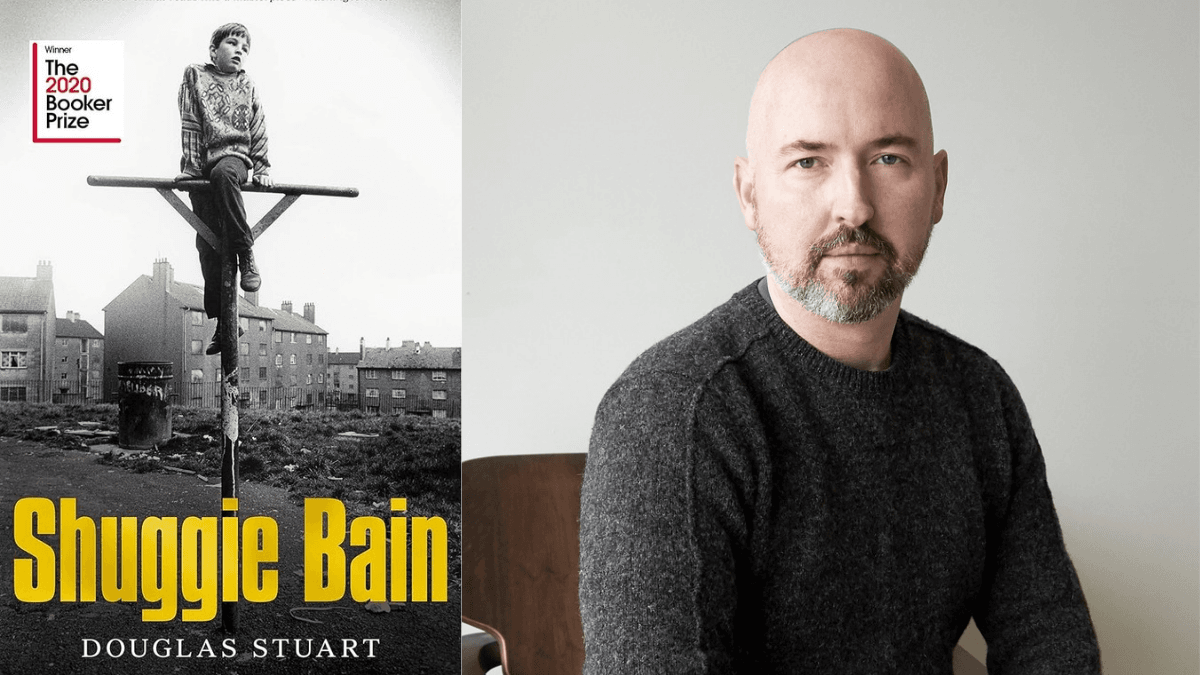

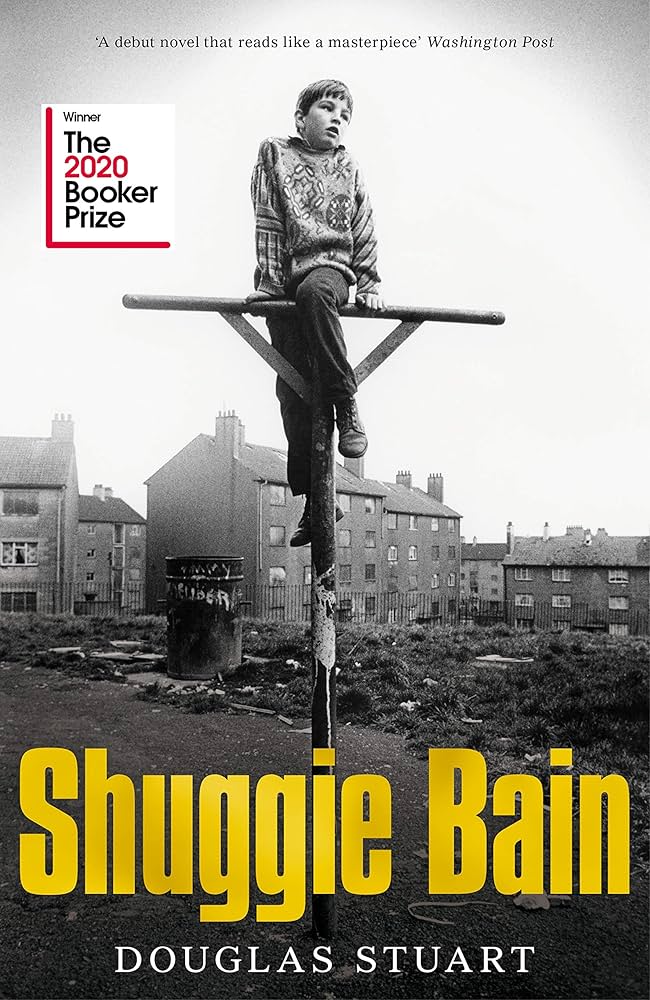

Douglas Stuart’s debut novel, Shuggie Bain, won the Booker Prize in 2020. The book is set during 1980s Glasgow, just as Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, and the effects of Thatcherism was seeping into the industrial city of Glasgow, leading to unemployment and poverty. The city is bleak; it is almost as though whilst reading, the world that the reader creates is a world where the images are a grim gray.

The book is set during 1980s Glasgow, just as Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, and the effects of Thatcherism was seeping into the industrial city of Glasgow, leading to unemployment and poverty.

The Booker prize winning novel is a deeply moving depiction of what it is like to live with a parent grappling with substance abuse. We first meet Shuggie Bain as a 16 year old cutting deli meat on the counter. He seems like a little boy on the cusp of something- possibly with big dreams. He lives, however, in a dingy bed sit owned by a Pakistani woman shared with several men seemingly in their middle age.

The book goes back eleven years and we see Shuggie as a five year old, living with his mother Agnes and his older brother and sister Leek and Catherine, who are both in their late teens.

The story of Shuggie Bain

In many ways, the real protagonist of Shuggie Bain is Agnes. She’s a woman at the precipice of her forties, with beautiful black hair. It almost seems as though a broken heart has fueled her drinking problem. She lives with her second husband Big Shug, after escaping the monotony of a loveless first marriage with a pure Catholic, who did, in fairness, take good care of her, but whom she felt almost no desire towards.

Big Shug sweeps her off her feet. She runs away from her husband, with Leek and Catherine to find a home with him, but soon enough the reality of the situation hits and she is forced to bring her family to her parents house, making her stifled, unsuccessful and small.

Stuart does a marvellous job. Agnes’ drinking, though awful, seems to be comprehensible. She wants to live a life larger than the one she has, and even if only for a few moments, drinking enables that. Shug slowly separates himself from her life after leading her out to a ‘safer’ space, in a different house at the edge of town, and then leaving her for good.

Shug slowly separates himself from her life after leading her out to a ‘safer’ space, in a different house at the edge of town, and then leaving her for good.

Her children deal with the substance abuse in different ways; Catherine gets married and goes off to South Africa, Leek creates art and Shuggie clings to his mother as the only world he has ever known.

Queerness and masculinity in Shuggie Bain

Shuggie is younger than his siblings, and it shows. The way that he carries himself is different- he adjusts his life around his mothers’ drinking, staying home to take care of her, going out to scourge for food, undressing his Mum so she’s comfortable, slowly wiping vomit off of her.

It almost seems like a quest for both Agnes and Shuggie to seem normal: Agnes seems to be an outcast due to her drinking problem and Shuggie seems to carry himself too effeminate to be considered a real boy, masculine enough. Unlike his peers, he shrugs off football, does not walk occupying space, as a ‘man’ should do, and he is teased relentlessly because of it.

A horribly touching sequence is this moment from when he was a little boy, being given this beautiful doll to play with and he takes her out. There is a puddle of oil through which sunlight passes and so Shuggie is bewitched by the colours of a rainbow. Thoroughly enchanted he dips his dolly into the enchanting swirl, only to be horrified, as he pulls her out that she is drenched in layers of oil and grime, and will never look as lovely again.

Years later, his classmates begin to suspect that he is a ‘wee poofter‘, as his eloquence sidesteps the natural Glasweigan dialect and the words that he chooses to use while talking seem to be comparatively posh.

Years later, his classmates begin to suspect that he is a ‘wee poofter‘, as his eloquence sidesteps the natural Glasweigan dialect and the words that he chooses to use while talking seem to be comparatively posh. His manners at such a rough edge of the town are unexpected, and therefore dainty, making him an easy target. His way of talking and the aspirations he has make him reminiscent of Pip, from Dickens’ Great Expectations.

The reader cannot help but grow fond of Shuggie as well as he shows us his world through a darkly comedic yet compassionate lens.

The fragility of substance abuse

Agnes is an unforgettable heroine. Despite being absolutely devoured by addiction, she is tender. Her personality almost overflows. She is trapped by alcoholism and by people around, who almost intentionally mislead her, abusing all of her vulnerabilities.

She has good intentions: to take care of her children, feed them well, ensure that they grow up to be kind, she even takes care of neighbours who have absolutely kicked her when she has been down in the past, but despite all of that she seems to be right in the fist of addiction, eaten up by all of its horrors.

She is a woman of pride, and ensures that Shuggie stays unashamedly himself too. Everyday, with her hair and make-up done, she climbs out of her grave and holds her head up high. When she has disgraced herself with drink, she puts on her best coat, and goes to find food for her children. She lets the world think that she will be okay.

When she has disgraced herself with drink, she puts on her best coat, and goes to find food for her children. She lets the world think that she will be okay.

Agnes is also sexually abused several times, and the sadness of it all breaks her, she almost believes that she drinks to feel happy, until the rush of it all comes back to her and she is swathed in sadness again- after which she drinks to forget herself, because she doesn’t know how else to keep the pain and loneliness away.

Ultimately, Agnes is killed quietly in her sleep by the drink, very much like Stuart’s own mother was. It is almost an unforgivable act to the reader, that Stuart lets her die. Shuggie Bain is, after all, presented as a work of fiction. The reader cannot stop rooting for her, cannot stop loving her and cannot stop wanting to save her, despite it all.

In an interview with The Guardian, Stuart has said ‘I don’t think I could have written the book (if my Mum was alive), because Shuggie is about loss and grief, so I wouldn’t have had the impetus. I didn’t just want to conjure up hardship and the pain of loving someone with addiction, but also the wonderful small things: her pride, her resilience, her dignity, her glamour. I wouldn’t have needed to have written it if my mother had still been alive.‘

Stuart hides nothing of the savagery of alcoholism in his novel. His prose is gloriously pictorial; the reader doesn’t read Shuggie Bain, he lives in its world. You are sickened by its viciousness in one sentence, tearing up at the next and then belly-laughing on the other page. It truly is a brilliant book.

The staggering thing is, despite Shuggie Bain being soaked in abhorrence, it is the softness that wins at the end.

About the author(s)

Treya covers art, culture, climate and the environment. She has aspired to be a journalist ever since she was little. She has reported for The Hindu and Deccan Chronicle among others and explores how feminism takes root in everyday life by leading sessions with young people on gender, digital safety and the "good girl" syndrome.