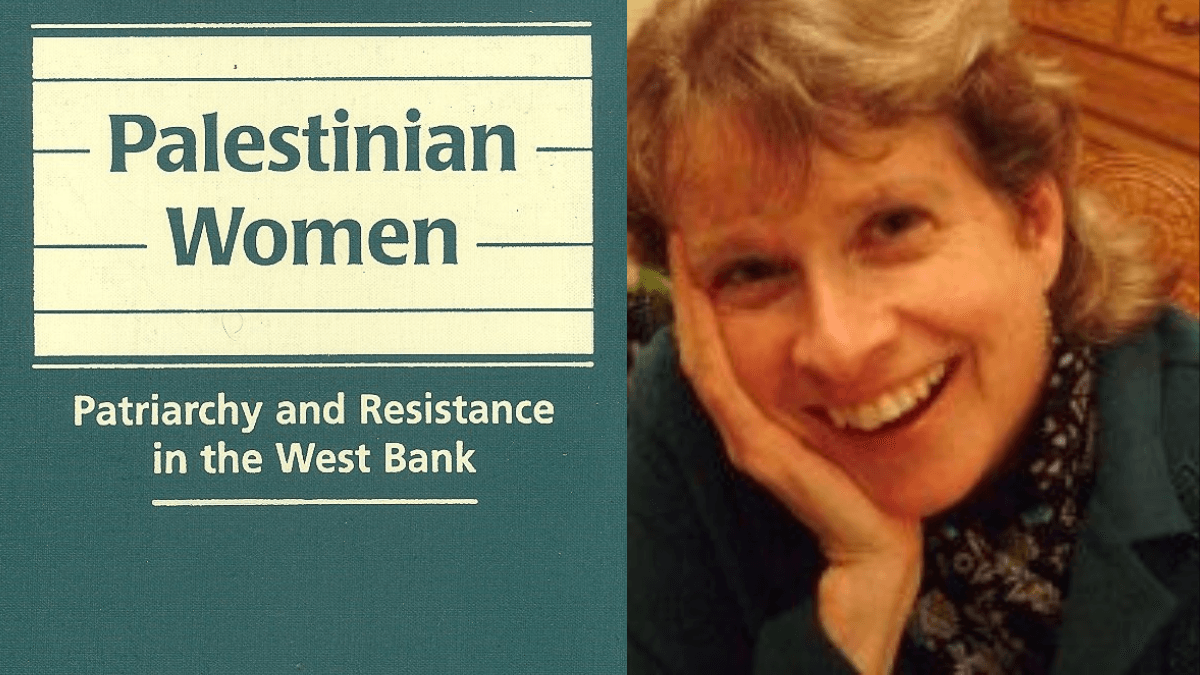

The question of Palestine is indeed raised to understand an almost century-old human rights violation. But it remains incomplete without paying analytical attention to its women, who are vulnerable to double discrimination and are the most marginalised. Cheryl A. Rubenberg, an eminent political science professor, came up with her major research breakthrough, “Palestinian Women : Patriarchy and Resistance in the West Bank.” Her area of specialisation was the Middle East.

Initially, Latin America was her focus of research, and then subsequently it shifted to the West Bank in Palestine after her visit to Beirut’s refugee camp. Owing to her stance on Palestine as an occupied territory, criticism was lobbed against her. Although she is known through her work, she is not well documented in history as a contributor to the Palestinian Rights Movement.

Rubenberg’s focus on Palestinian women in the West Bank

The book is specific to the West Bank in Palestine. The women from the villages and refugee camps are the focus, who are mostly invisibilised in discourses and discussions on the Palestinian struggle. It was Rubenberg’s sincerity to cover up the refugee camp and village women in the argument. She mentions it is Palestinian women who belong to the upper, middle, and upper-middle classes that get social and demographic representation in articles, academic discourses, and students’ discussion forums. These refugee camp and village women constitute 60 percent of those who are marginalised from visibility. She is inclined to bring to the forefront social stratifications and gender-based inequalities in camps, villages, and the labour market in the West Bank. Such an argument is indeed needed to broaden the perspective about Palestine when it comes to understanding the people’s struggles. In addition, she undertook qualitative and quantitative methods to corroborate her argument. Though this is a case study carried out on some women and their individual experiences.

Palestinian women need an autonomous space to share their experiences, as their vulnerability lies at two levels. Institutionalised discrimination, or apartheid, is imposed upon them as a result of settler colonialism on the one hand. On the other hand, they are still struggling to assert their rights. The book opens with some shared experiences of the Palestinian women. There was a woman named Umm Hassan, aged 49, who affirmed that there should be discussions about women as individual beings to comprehend their situation.

Another woman, named Miriam, aged 42, drew a line of distinction between villages and cities and their lives in them. Villages are perceived to be narrow-minded and have limited opportunities, while cities offer more democracy to them. Even though it is apparent to the enlightened people that imperialism and colonialism have brought complete human rights violations to Palestinians, and women and children are the worst sufferers.

There was so much heterogeneity regarding women and their relation to patriarchy that Rubenberg came across during her research survey. Some women accept societal norms and give justifications for their positions, while some are reluctant to adhere to them but are compelled by patriarchal society to take up socially constructed roles, and some denounce societal values and expectations as they understand their repercussions on them. To be concise, she mentions, “dominant power (Patriarchy) is not merely oppressive, but productive too. Individuals are not merely its agents but passive receipts too.”

Rubenberg’s arguments revolve around gender, culture and politics

The gist of Rubenberg’s argument revolves around the interconnectedness between gender, cultural norms, and politics. One fails to contribute to the Palestinian independence struggle if one understands them as discrete concepts. She further asserts that both women and men fall victim to patriarchy. It does not seem possible for women to be free unless men are bound to patriarchal notions.

Throughout the book, it is articulated that the dominant power system does not work in isolation, but it breeds societal norms and expectations that unleash political and economic constraints on women. Political and economic dynamics have taken place since the inception of imperialism-settler colonialism, bringing changes in family arrangements and sustaining traditional roles for women.

For instance, Israeli colonialism led to the Nakba (Catastrophe) in Palestine, resulting in a trail of displacement, suppression, and devastation of Palestinians and their belongings. Due to this, men started migrating to other countries to earn a livelihood, which affected women to a great extent. In their absence, they were under the guidance of ‘closest male relatives‘ who controlled them to remain confined to traditional roles.

In subsequent times, as a result of the 1987 Intifada or the period of uprising against human rights violations, long-term imprisonments and killings put a double burden on women to maintain households and earn a livelihood through traditional activities, including sewing and knitting. Although some women were engaged in protests. But for camp and village women, it remained even more restricted when it came to free movement and education due to societal expectations and notions.

The intifada was largely male-dominated. Women were reduced to supportive roles rather than taking up leadership positions. There is a recorded experience of a camp resident, named Karma, aged 32, who states that it is not actually expected from women to be active in politics but to provide emotional support and comfort to men involved in politics.

In education, people may get confused between the recent studies that show female participation in lower and higher education is greater than that of men and Rubenberg’s research work, whose emphasis is laid upon colonial expansion and societal barriers that stop women from getting an education. Well, it is not arduous to understand her focal point on refugee camp and village women in the West Bank who are deprived of educational rights. Education is seen as a threat to the dominant power structure. That is why several notions are constructed around it to sustain power dominance. For instance, in the research community, most women want education for girls but to make them better mothers, daughters-in-law, and wives. Some of them do not even understand the importance of independent government functioning and the effective implementation of laws for imparting education to girls to have agency. Besides limited economic resources and extreme poverty, leaving the camp for education brings character assassination to girls. This is considered an important factor for dropout rates among girls.

The predominance of women in the informal sector in the West Bank

According to an article on Al Jazeera, women empowered other women by teaching them to turn their traditional roles into income sources during the first Intifada. However, the book affirms the informalisation in the West Bank that incorporates 55.6 percent of female workers in predominance. The informal sector consists of different categories such as husbandry, plant production, crafts, household industries (sewing, house cleaning, knitting, home food processing, catering, cooking, babysitting, etc.), and bastat (street vendors). This sector is called ‘the most exploitative sector,’ as it requires labour power but does not ensure sufficient income for women. It is relevant to note that women are forced to sell their labour power to sustain traditional gender roles.

In fact, within the confines of their traditional activities, women even have to bear the brunt of the social notion of impurity attached to house cleaning, which is deemed more impure than institutional cleaning. Israeli colonialism-led economic devastation and migration of men to other countries are two prominent factors that led house cleaning to prevail.

The absence of independence, human rights, economic, political, and social stability, and, more importantly, gender considerations further makes societal expectations stringent. Rubenberg’s research analysis states that women have limited choices due to the non-functioning of an independent state.

Rubenberg’s work, a major contribution to the Palestinian struggle

Rubenberg’s work on Palestinian women should be acknowledged as a major contribution to the Palestinian struggle. It is a reminder to incorporate gender considerations into a comprehensive study of Palestine.

Indeed, Israeli colonialism has left a long-lasting stagnation in Palestinian livelihoods, but the patriarchal system in Palestine does not let women lead the movement to dismantle stagnation.

About the author(s)

Nashra Rehman finds her profound interest in addressing the plight of Muslim women and their unappreciated marginalisation. Her focus remains on bringing a novel argument to life.