Contentions surround parental approval for a minor to create a social media account as per the Draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025

Acting early on its ‘New Term’s Resolution,’ the Union Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MEITY) made the Draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025 (hereinafter, Rules) public to seek public consultations on the 3rd of January, 2025, through the MyGov portal. These submissions are allowed till the 18th of February but shall, however, be kept confidential by the Central Government. The draft rules attempt to give effect to the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, which was enacted in 2023 and replaced the Information Technology (IT) Act of 2000 and the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules of 2011. Even as the Indian Penal Code was replaced by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 164 years after its enactment, the evolving realm of IT has necessitated a revamp of legislation within two decades.

Provision in question

One of the key issues addressed in this legislation concerns itself with children’s engagement with the Internet and New Media. To implement Section 9 of the Act, the draft Rule 10 puts the onus upon the Data Fiduciary (DF), identified as social media companies, e-commerce firms, and online gaming companies, to adopt appropriate measures to gather consent from the parent or lawful guardian of a minor. They have to verify their age and identity and use ‘reliable details,’ that are either already with them if the parent is a user of the platform, voluntarily provided, or deposited in officially issued virtual tokens mapped to these details. Exemptions have been granted to certain sectors, including education and health, where no verifiable consent by the parents is required and tracking, targeting advertising, and behavioural monitoring of children is permitted.

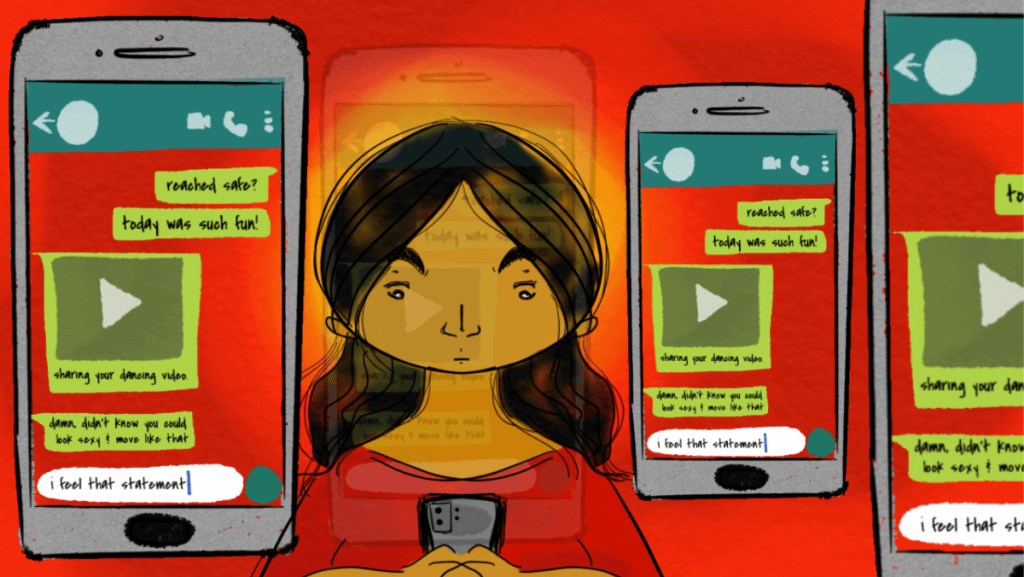

Section 9 also prohibits targeting children with advertisements, tracking their behaviour, or processing data that might harm them. Non-compliance can render the Data Protection Board to impose penalties of up to ₹200 crore on the DF. However, no penalties have been mentioned in the draft rules.

Last month, the Australian government enacted the The Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Act 2024, which restricts children below the age of sixteen years from having an account on social media. Technological giants such as META, owner of Instagram and Facebook, and TikTok are liable to stop minors from logging in or pay fines up to $32 million. Currently, the law is on trial, and it will come into effect in a year. The distinctive feature of this ban is that unlike France, the US, and now India, where parent’s consent is required, this ban is absolute.

A similar law was enacted in Florida wherein, within 90 days beginning from the 1st of January 2025, social media sites are required to delete accounts of children under the age of 14 years or face fines up to $50,000 for each violation. Those who are 14 and 15 years old require parental consent.

Securing children from cyberspace

This is the first major legislation enacted by the newly elected Indian Parliament and probably the last in the series for Australia, which goes to polls in 2025. But what has triggered this newfound interest of legislatures in child rights and the cyberspace that they are risking opposition from free speech advocates and the largest technological conglomerates in the world?

1. Rise of Misinformation: With the mediascape being democratised, as the internet penetrates the remotest corners of the world, anyone can leave a digital footprint without being held accountable for what information they disseminate. The pandemic saw rampant spread of not just the virus but also false claims regarding treatment and cure. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s decision to replace fact-checkers with community-based posts in the US has raised concerns amongst media experts.

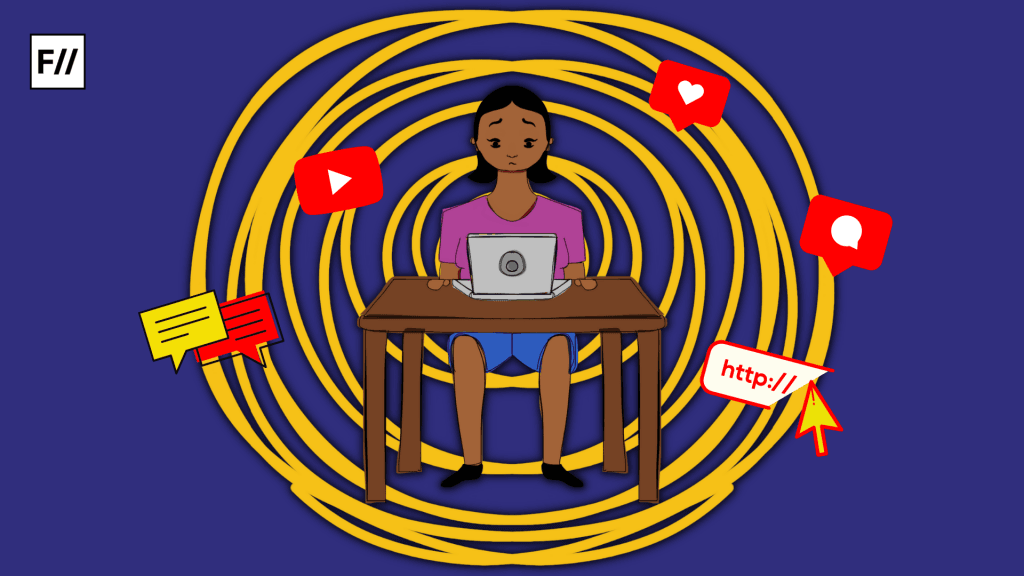

2. Social Isolation: Post the pandemic, a return to ‘normal,’ was not possible as the quarantine had insulated people, especially children, who found it difficult to interact with others in the physical reality where they were devoid of emoticons and automated messaging that could produce conversations.

3. Rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI): Though AI is not a novel phenomenon, it broke through in the post-pandemic world where the focus was shifted from rearing humanity to upgrading technology. Children found elementary tasks of academics, such as note-making, homework, basic mathematics, or even attending lectures, difficult. In search of ‘ease,’ and readiness with quality, many students resorted to using AI and mastered the art of paraphrasing to escape plagiarism checks.

4. Content Creation and Consumption: As many businesses permanently committed to the ‘Work from Home’ model, individuals got inspired to monetise their own personal space and utilised social media platforms to promote themselves, their initiatives, businesses, ‘good practices,’ etc. The onset of the ‘influencer culture,’ greatly impacted children who idealised and attempted to replicate unrealistic and maladaptive ways of living. Some children became targets of cyber scams and cyberbullying and found themselves unable to reach out to parents given the scare and socially distanced peers. This had a debilitating effect on their mental and physical health, with the rates of youngsters with symptoms of anxiety and depression nearly doubling in the pandemic period, as per the American Psychology Association.

5. Concerns regarding violation of privacy: The mandated requirements of submitting personal information before creating an account, algorithm-driven content consumption, and instances of data breach have brought DFs under speculation and legal challenges by the people and governments. Institutions and companies organising mandated cybersecurity workshops and training sessions are testimony to how the importance of digital literacy to ensure safe and responsible digital citizenship is being realised.

Deepening social inequality

However, several concerns remain. Other than the obvious contentions concerning freedom, human rights groups find such restrictions and the need for parental consent problematic, as they do not account for the most vulnerable youth, those who were already socially excluded, such as the LGBTQIA+ community.

For India in particular, Rule 10, which mandates verifiable consent from parents after their digital identity verification, is exclusionary towards the illiterate parents who lack digital literacy and access to e-services such as the Digi-Locker. The Digital Locker Authority, which was formed in 2016, has no listed digital lockers in its directory. A digital divide is created where children of such parents are excluded from accessing social media or essential digital services such as e-learning platforms.

Second, the over-reliance on government-sanctioned digital databases for verification is questionable. Though these systems are robust, they are still inaccessible and even unknown to a significant portion of the population. Moreover, it is an exaggerated assumption that everyone has Aadhaar-linked digital credentials or other such digitally verifiable proof. This provision is not inclusive of the diverse conditions of the people of India. Privileging the right to privacy over rights to access information and, to a certain extent, education and opportunity is contentious.

Third, the provision is reliant on self-declaration of one’s status as a minor. Therefore, effective age verification remains a challenge as, for example, Meta, which had sought exemptions to use behavioural data for age assessment, can now do so only to verify adulthood.

Fourth, in India, a minor is defined as a person below the age of 18 years. This age limit is higher than any other country that has enacted similar legislation, and it covers a wide demographic range, thereby increasing the burden on the DF.

Fifth, a disproportionate burden is put on smaller and newer DFs who do not have existing adult user data for verification and will have to source the same from a third-party database.

Sixth, if multiple members use the same device, the registered information on the DigiLocker will fail to differentiate. Moreover, linking the minor’s data with that of their parents creates a new dataset where the online behaviour of the parent is also made available to the DF.

Seventh, ‘age-gating,’ in a patriarchal society, reinforces the permission-seeking behaviour that is often expected from girls. This creates an atmosphere of surveillance by the family and state.

Lastly, the standard of determining ‘age-appropriateness,’ of digital content and classes of harm that children are to be protected from are not mentioned.

Certain measures that the government must take towards accommodating differential socioeconomic statuses of people to implement this rule are:

i. Forming alternate mechanisms and independent authority that will be in charge of verification,

ii. Digital literacy and awareness programs, and

iii. Providing financial aid to enable access to digital services.

As the world advances in the realm of IT, India must keep up but at its own pace.

About the author(s)

Second year student of Media Studies at CHRIST (Deemed to be University), BRC, Bangalore. A trained Kathak dancer, theatre artist and political nerd.