You can almost taste the sweetness of the cactus pear when it is devoured on screen by protagonist Anand halfway through Sabar Bonda. He is both hungering for a love he has lost with the death of his supportive father, and relishing a love he has gained from reconnecting with an estranged friend.

Longing and desire surface in several visceral moments across Rohan Kanawade’s debut film, Sabar Bonda, which is set in rural Maharashtra over the 10 days of a mourning ceremony. The first Marathi title ever to compete at Sundance, it won the festival’s world dramatic cinema competition.

Longing and desire surface in several visceral moments across Rohan Kanawade’s debut film, Sabar Bonda, which is set in rural Maharashtra over the 10 days of a mourning ceremony.

There is no one way to grieve, but in the immediacy of funeral proceedings, there is sometimes no way to grieve. For Anand, the traditional mourning period is strained by a sense of duty. As soon as he arrives from the city to his ancestral village, keen-eyed relatives supply a wishlist of rituals and rites.

At one point in Sabar Bonda, hesitating because of all the decorum expected of him, he asks his friend Balya: ‘Am I allowed to go out?‘ Balya shrugs naturally, ‘Why not?‘ Their small exchange signals a sense of permission: To leave behind stifling perfunctory condolences and go where Anand can breathe for the first time, in the safe presence of a friend.

Lost and found

As conversations slowly unfurl between Anand and Balya in Sabar Bonda, we learn of their shared childhood summers as well as their shared knowledge of each other’s queerness. It is not only the grieving rituals they want to get away from, but also the inevitable, unbearable advice to ‘find a ‘nice girl‘ to marry‘.

While city-dweller Anand’s parents accepted his sexuality, they lied to relatives that he would marry ‘when he finds a nice girl‘ to stave off questions. Balya’s rural family has never acknowledged that he does not want to marry, and try to talk him into responding to a ‘nice girl’ match.

Sabar Bonda, with cinematography by Vikas Urs, uses photograph-like rounded corners — almost as if to keep the two characters’ budding affections safe, protected, and free of sharp edges.

Sabar Bonda, with cinematography by Vikas Urs, uses photograph-like rounded corners — almost as if to keep the two characters’ budding affections safe, protected, and free of sharp edges. All the softness that emerges from their scenes together has another important effect. It makes the small aggressions in other scenes much more noticeable. For instance, no matter how briefly family members murmur suspicions and concerns, the harsh effect of their words is clear.

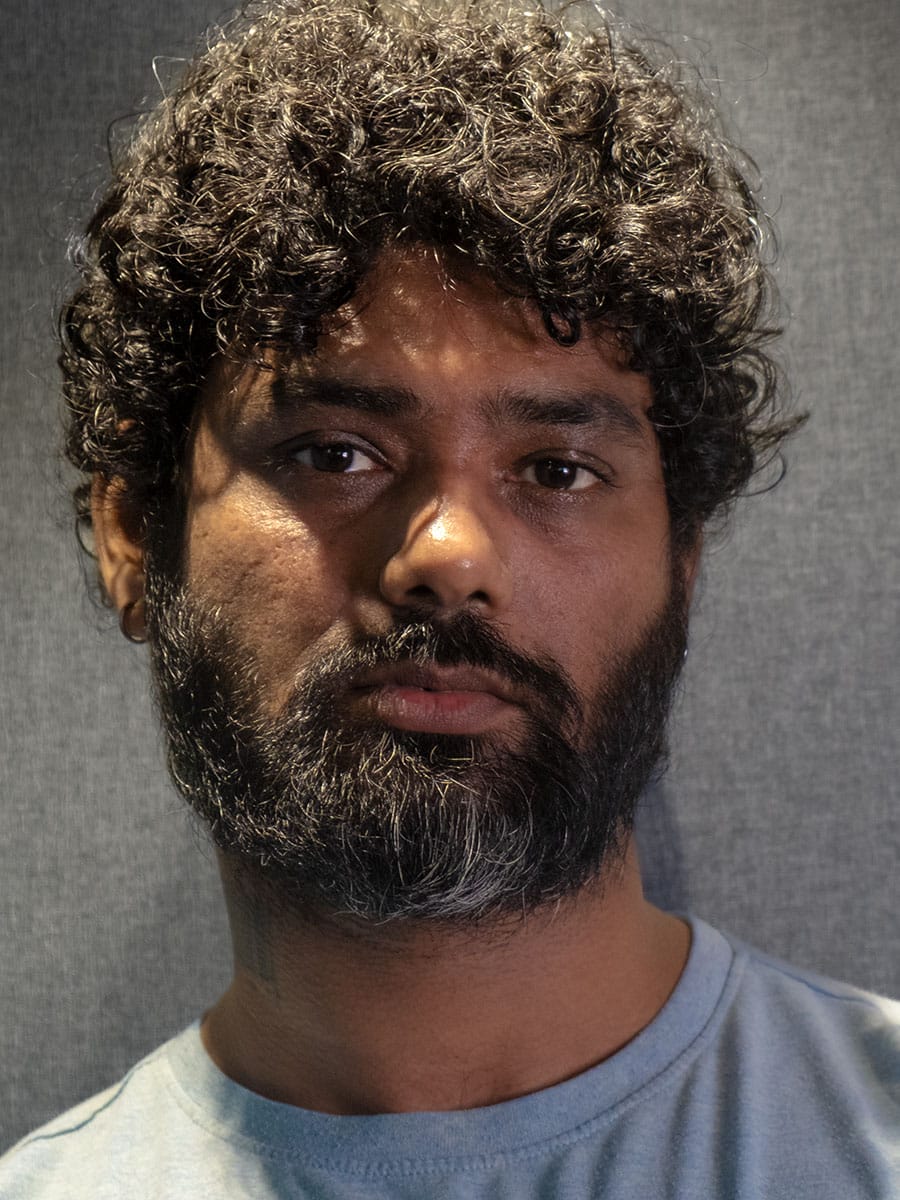

The cast of Sabar Bonda delivers remarkably contained performances. Bhushaan Manoj as Anand embodies loneliness in his slumped shoulders and downcast gaze. Playing Balya, the bolder of the two main characters and someone who labours physically for a living, Suraaj Suman is sprague and spry.

As a woman in a traditional household, Anand’s mother is torn in various directions—even as a wife in mourning, she must remain a compliant daughter-in-law, or turn into a protective mother where necessary. Jayshri Jagtap makes each of these shifts with unmanufactured grace in Sabar Bonda.

Sabar Bonda: nothing quite like being known

What Balya offers at a time of loss—presence and permission—is something that Anand’s father also gave him during his lifetime. An undemanding kind of acceptance that his son didn’t have to earn. ‘You know yourself and that‘s important,’ Anand remembers him saying when he came out as queer.

‘You know yourself and that’s important,’ Anand remembers him saying when he came out as queer.

He recounts this more than once, such was the impression that sentiment made. His mother’s acceptance had been promised even earlier, as another scene reveals: ‘I always knew. Your father tried to explain things to me, thinking I would not understand. But I always knew.‘

Not a lot of films are made about supportive parents. Perhaps that does not make for a compelling plot. But this one is more from the heart than about the plot. It is inspired by Kanawade’s own lived experience of losing his father, a taxi driver who supported his son’s personal and professional desires. Sabar Bonda is a deeply felt and observed tribute both to queer love and to parents who understand.