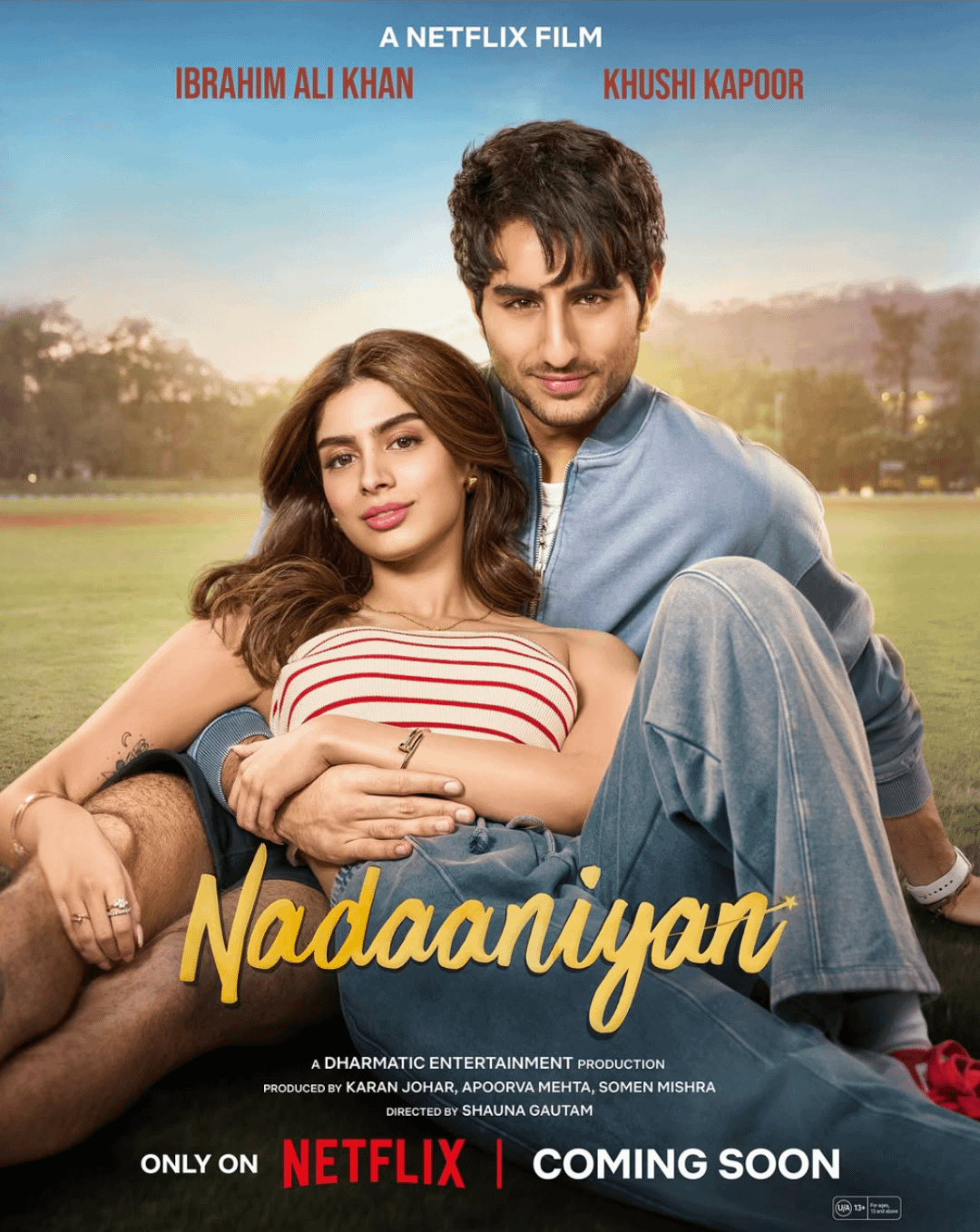

If you ever wondered what happens when money, privilege, and a Netflix deal collide in a spectacular implosion of bad filmmaking, look no further than Nadaaniyan. It is a coming-of-age college drama that follows Arjun (Ibrahim Khan), a brooding rich kid with an identity crisis, as he navigates the hyper-curated world of Delhi’s elite. The plot, if one can even call it that, centers around a debating competition that apparently holds the power to change lives—though how, we never truly understand.

The plot, if one can even call it that, centers around a debating competition that apparently holds the power to change lives—though how, we never truly understand.

Somewhere in this mess is Pia (Khushi Kapoor), a girl so unnoticed by her own family that it takes a complete stranger for her parents to realise she might have a future. Together, they attempt to convince us that their story is one worth telling.

The script and the enactment of Nadaaniyan: a match made in heaven

Watching Ibrahim Khan and Khushi Kapoor act is akin to witnessing two rich kids perform a high-school skit where no one has the heart to tell them they lack even a shred of talent. Ibrahim, playing Arjun—our reluctant, brooding protagonist—is what happens when you cast someone whose main qualification for the role is a surname and a six-pack. His version of expressing conflict involves alternating between one of two facial expressions: mild confusion and absolute disinterest.

Khushi Kapoor, on the other hand, brings the kind of energy to the screen that makes you wonder if her character, Pia Jaisingh, is even aware she’s in a film. The chemistry between the leads is so non-existent that the air between them feels more palpable than their supposed romance. Every time they lock eyes, it’s less Kuchh Kuchh Hota Hai, more two strangers accidentally making eye contact on the Delhi Metro.

The film also features Agasthya Shah and Orry, Instagram influencers attempting to act and make the film feel smart by virtue of it being meta and aware. Shah’s role as Arjun’s debating club rival—because yes, this film really thinks debating is the ultimate battleground for cinematic conflict—feels like an extended skit he would upload with the caption: POV: When You Try to Out-Debate the Rich Kid Who Doesn’t Have to Work for a Living.

If Nadaaniyan were to take the phrase ‘suspension of disbelief’ literally, it would strap it to a rocket and launch it into another galaxy. The film operates in a world where logic has not just been abandoned but actively shunned. Take, for instance, the baffling subplot where Pia’s parents—played by Suniel Shetty and Mahima Chaudhry—pay attention to their daughter for the first time in 18 years because Arjun, a near-stranger, tells them she has the potential to be a lawyer due to her “razor-sharp brain.”

The film operates in a world where logic has not just been abandoned but actively shunned.

The proof of this so-called sharpness? She delivers a catastrophically terrible argument against free vaccines during a pandemic—an argument that reads less like a display of intellect and more like a love letter to Mr. Poonawalla’s vaccine empire.

Perhaps we expected too much from a film that earnestly believes having a woodfire oven in the cozy outdoor home of a Delhi (sorry, Greater Noida) doctor and a teacher in an elite school for the ultra-rich, lit by warm tones, is an accurate representation of middle-class life. The middle class here is not a socioeconomic reality but an aesthetic—a curated illusion meant to serve as the perfect backdrop for a story that mistakes privilege for relatability.

Nadaaniyan wants us to believe in romance beyond class divides, but there are no divides here—just mind-numbingly dumb cliques masquerading as friends, negligent parents suddenly realising their child exists, and vague aspirations to go to an unnamed “abroad” school via victory in an unnamed “international” debate competition.

We can only wish Dharma had let us fill in the blanks ourselves. Nothingness would have been funnier, more meaningful, and far less painful than what we got.

Logic? We don’t do that here

The script is where Nadaaniyan truly shines—if you consider shining to be the equivalent of watching a car crash in slow motion. The film prides itself on absurdity, mistaking it for quirky genius. At one point, Arjun, in an attempt to prove himself as the superior debater, takes his shirt off. Because, of course, nothing says “I am a man of intellect” like a perfectly sculpted torso glistening under strategically placed fairy lights.

Then there’s the debating club showdown, which feels less like a war of words and more like an inside joke no one let the audience in on. The crowd cheers at random intervals, siding with whoever has the last word, reminiscent of that How I Met Your Mother episode where Robin convinces Barney that people at MacLaren’s will cheer for anything. The only difference is that in Nadaaniyan, this wasn’t satire—it was meant to be a pivotal moment in the film.

Perhaps the most infuriating part of Nadaaniyan is how it wants to be self-aware about its own nepotistic casting but lacks the intelligence to do so with any actual impact.

Perhaps the most infuriating part of Nadaaniyan is how it wants to be self-aware about its own nepotistic casting but lacks the intelligence to do so with any actual impact. The film opens with a cringeworthy attempt at breaking the fourth wall, where Arjun jokes about how “connections don’t matter” in the industry. Except, instead of coming off as Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s razor-sharp meta-commentary, it feels more like a rich kid casually acknowledging their privilege in a room full of struggling artists and expecting applause.

This is where watching Superboys of Malegaon before Nadaaniyan becomes an almost tragic exercise in contrast. The dreamers of Malegaon put their lives on the line—money, jobs, relationships—to create something real, something that mattered. Meanwhile, Nadaaniyan is what happens when people with unlimited resources squander the opportunity to create something meaningful and instead settle for writing dialogues like, “Tumhare naam mein Sharma hai kya?” to make fun of a shy boy, or using “Tum toh global warming ki wajah ho” as a pickup line.

Aesthetic over substance: the reelification of cinema

At times, Nadaaniyan looks like it was shot with the singular intention of being turned into a Pinterest mood board. The cinematography is excessive in its desperation to be called stunning, but it only ends up feeling like a colour-graded hallucination. The South Delhi setting, which could have added layers to the film’s narrative, is instead reduced to a postcard version of itself, where no one seems to belong anywhere.

The soundtrack, too, follows the “If It Sounds Good, It Must Be Good” philosophy. Dreamy lo-fi beats accompany long shots of Arjun staring into the distance, as if he’s contemplating life’s deepest questions, when in reality, he’s probably wondering why he signed this film. The background score swells at every possible moment, attempting to infuse emotion into scenes that have none. It’s the cinematic equivalent of adding excessive seasoning to an undercooked dish—no matter how much you try to mask it, the rawness still shows.

This is a film that should have been a satire but instead plays out like a very expensive inside joke that only benefits those who made it.

This is a film that should have been a satire but instead plays out like a very expensive inside joke that only benefits those who made it. It’s frustrating not because it’s bad (which it is) but because of the sheer waste of resources, talent, and potential. Bollywood has the ability to produce sharp, evocative coming-of-age films (Wake Up Sid, Udaan, Dil Chahta Hai), but instead, we get Nadaaniyan—a film that is neither self-aware enough to be meaningful nor ridiculous enough to be enjoyably bad.

It’s not a film; it’s a rich-kid vanity project disguised as cinema. And the saddest part? It won’t be the last of its kind.