There is no character in Hindu mythology perhaps as revolutionary as Radha. She occupies a paradoxical position in the Hindu pantheon; she is central to Krishna worship yet conspicuously absent from mainstream texts. Despite being Krishna’s foremost beloved, Radha remains missing from the Bhagavata Purana, the most renowned scripture on Krishna’s life, as well as the Mahabharata and its appendix, the Harivamsha.

This absence is not entirely accidental: it is a silence that speaks volumes about something patriarchal authorities found threatening about Radha.

The centers of power, the male Brahmanical authorities who determined which stories warranted inclusion in the official canon saw something formidable in Radha’s narrative, something worth controlling through omission.

The centers of power, the male Brahmanical authorities who determined which stories warranted inclusion in the official canon, saw something formidable in Radha’s narrative, something worth controlling through omission. What makes this exclusion highly deliberate rather than accidental is the evidence that Radha existed in earlier traditions long before these canonical works were composed.

References to Radha appear in the first-century Gatha Saptasati by King Hala and also the fifth-century Panchatantra. She is also mentioned in various Puranas like the Padma Purana, Vayu Purana, and Matsya Purana. Her presence in these diverse sources makes her absence seem not an oversight but an editorial decision.

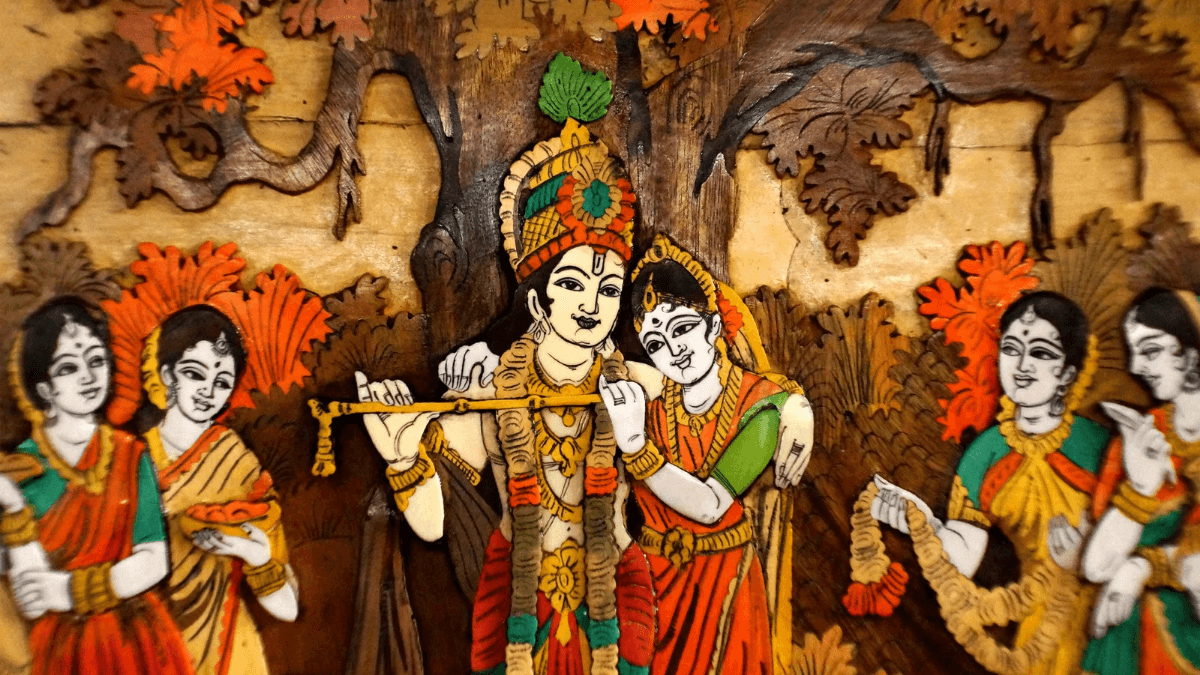

Radha first appears prominently in Jayadeva’s twelfth-century Gita Govinda, nearly 1,500 years after the earliest Krishna narratives. This text emerged from regional devotional movements. Her emergence through non-canonical channels suggests a grassroots popularity that institutional religion did not officially sanction.

Her emergence through non-canonical channels suggests a grassroots popularity that institutional religion did not officially sanction.

The gravitational pull of her narrative proved too strong to erase, yet too dangerous to canonise. This pattern of exclusion from mainstream texts while flourishing in popular devotion reveals much about the nature of patriarchal anxiety concerning female autonomy.

Radha’s threatening autonomy

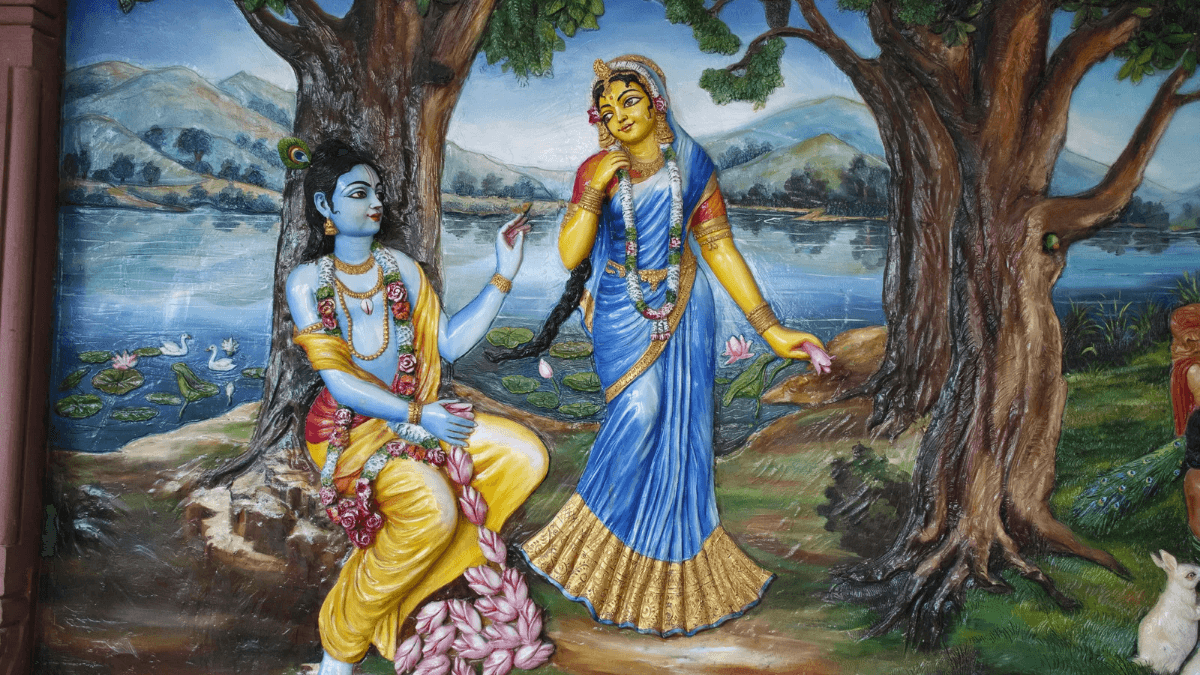

What made Radha so threatening to the patriarchal order? She represents perhaps the most visceral and indisputably disruptive expression of divine love in the Indian tradition. Unlike canonical goddesses like Sita and Parvati, whose desires were channeled through marriage, Radha’s desires operate outside patriarchal control.

Her love for Krishna isn’t sanctioned by family or society but arises from her own will. While Sita’s spirituality comes through her suffering and self-sacrifice, reinforcing the notion that women’s spiritual worth is tied to their endurance of hardship, Radha achieves spiritual distinction through her emotional capacity and her connection to Krishna based on mutual bonding rather than hierarchical protection. This model of female spirituality achieved through desire rather than denial presented a dangerous alternative to patriarchal religious frameworks.

Vaishnava poets like Vidyapati and Chandidas, who came after Jayadeva, produced verses from Radha’s perspective perhaps because they recognised the need for a love-goddess whose story wasn’t governed by maryada (dignity) and societal rules. Radha’s narrative in that sense is not colourless but glamorous and irresistible.

She is who she is without any apologies, a model that threatened the foundations of patriarchal control over women’s emotional and sexual lives. In her, devotees found a figure who validated the possibility that the deepest emotional truths might be accessed through authenticity rather than social conformity. This made her both irresistible to devotional movements and threatening to institutional orthodoxy.

The exclusion of Radha becomes even more significant when contrasted with the canonical inclusion of other female figures. Draupadi’s polyandry, potentially threatening to patriarchal order, was carefully contained within the narrative by making it the result of a mother’s misunderstood command and divine destiny. Her sexuality, though unusual, remained under male control through marriage and divine sanction.

Sita’s challenges to Rama are similarly contained through narrative consequences that ultimately reinforce patriarchal values. Her questioning of his judgment leads to her forest exile, and her final assertion of independence results in her return to Mother Earth. The narrative seems to reward her submissions and perhaps even criticises her assertions of will.

While both Radha and Sita are considered incarnations of Lakshmi according to several texts, Sita survives as a goddess far more prominently than Radha.

While both Radha and Sita are considered incarnations of Lakshmi according to several texts, Sita survives as a goddess far more prominently than Radha. Sita is enshrined in temples with Rama, while Radha is often absent from early Krishna temples. This differential treatment reveals the patriarchal preference for the devoted wife over the autonomous lover.

The architectural and ritual exclusion of Radha mirrors her textual erasure, both serving to marginalise a model of femininity that could not be easily controlled.

Containment strategies to erase Radha’s story

Radha offered women a dangerous template for spiritual and emotional fulfillment outside the patriarchal structures, a model for refusing the typical narrative of feminine submission that the status quo perpetuated through literature.

Her agency extends beyond mere romantic choice to spiritual authority as she achieves divine status not through suffering or association with a male deity, but through the strength and integrity of her own experience.

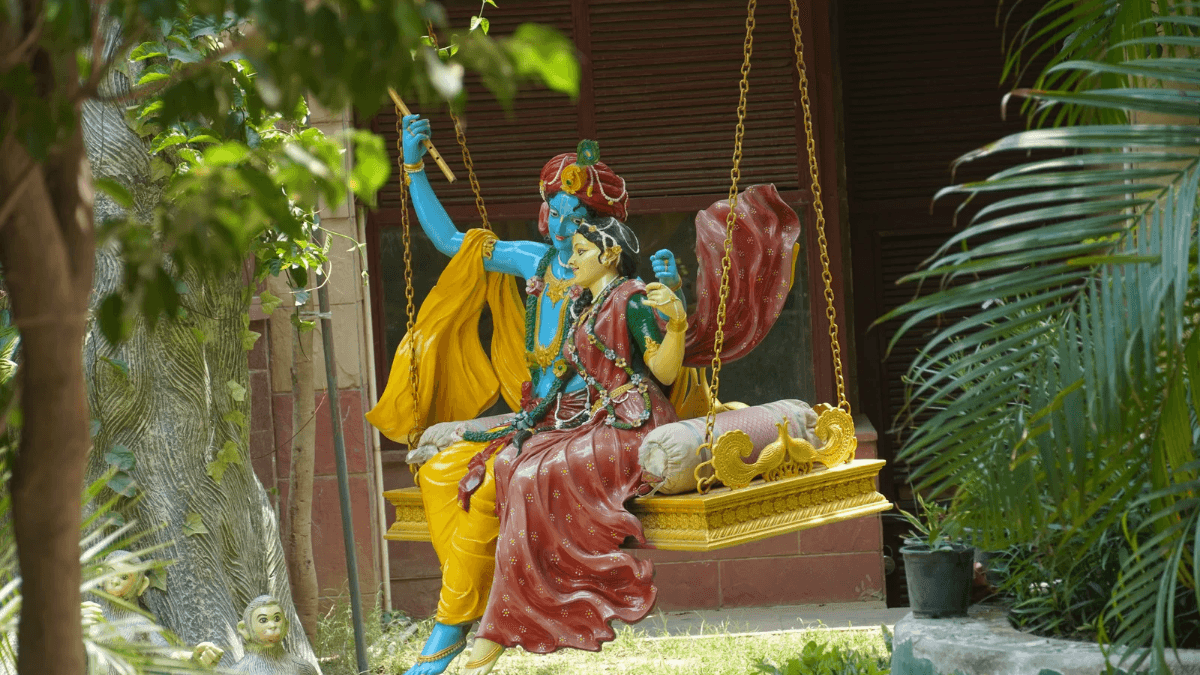

Once Radha became too popular to ignore, later texts attempted to legitimise and contain her disruptive potential through theological maneuvers. The Brahma Vaivarta Purana explains that Radha was married to an impotent man (Ayan/Rayana) who was “a part of Hari (Vishnu)” himself, creating a divine justification for what would otherwise be adultery.

It further claims that Radha and Krishna were married in a “secret” ceremony before she left for Vrindavan. The Devi-bhagavata Purana mentions that Radha is Shiva incarnate and Krishna is Kali, thus sanctifying their union through divine disguise. These retroactive theological justifications reveal the anxiety her character provoked. Her relationship with Krishna required extensive divine explanations to fit into patriarchal moral frameworks.

Another domestication strategy was to depict Radha’s story as cautionary. Her pain and longing for Krishna were presented as the consequence of an illicit relationship. In some traditions, she was portrayed as an abandoned woman who caused embarrassment to her society and in-laws.

In some traditions, she was portrayed as an abandoned woman who caused embarrassment to her society and in-laws.

Simultaneously, to legitimise her relationship with Krishna, later texts depict her as an extension of God himself. Her story is transformed from the love between two beings into a symbol of the mortal soul’s yearning for the divine, shifting the narrative from threatening human desire to acceptable spiritual allegory. These competing interpretations reveal the struggle between devotional movements that embraced her revolutionary potential and orthodox institutions that sought to contain it.

Perhaps most dangerous was Radha’s spatial freedom. Unlike Sita, whose movements were carefully contained within domestic or sanctioned spaces, Radha’s love occurs in forests and pastoral settings, in liminal spaces away from social surveillance. Sita’s story emphasises her domestic skills and patient suffering even in exile.

Draupadi, despite her fiery nature, ultimately fulfills her role as wife to the Pandavas within palace and court contexts. Radha, however, remains fundamentally undomesticated. Her love occurs in natural spaces outside the controlled domain of the household. This freedom mirrors her emotional autonomy, both representing forms of female independence that patriarchal systems have historically sought to restrict.

From male mediation to contemporary resistance

The male poets who eventually gave voice to Radha represent both empathy with and appropriation of female experience. Even though Jayadeva brought Radha from folk literature into mainstream narration, he maintains Krishna as the central subject of his work, while Vidyapati’s poetry shows a “radical interest in female concerns.”

Even though Jayadeva brought Radha from folk literature into mainstream narration, he maintains Krishna as the central subject of his work, while Vidyapati’s poetry shows a “radical interest in female concerns.”

Despite their genuine attempts to inhabit female subjectivity, these male poets ultimately contained Radha’s voice within certain acceptable frameworks. The revolutionary potential of Radha’s voice is simultaneously revealed and constrained through these male articulations. This paradoxical mediation of giving voice while maintaining control reflects broader patterns in how patriarchal culture both acknowledges and limits female expression.

A striking exception to this male mediation is Muddupalani’s eighteenth-century Telugu erotic poem, Radhika Santwanam (The Appeasement of Radha). As a female court poet writing about Radha, Muddupalani offered a rare glimpse of female desire articulated through a woman’s perspective.

Significantly, her work faced censorship in colonial and post-colonial India, demonstrating continued patriarchal discomfort with female sexual agency, especially when expressed by a woman author rather than filtered through male imagination.

Radha’s canonical exclusion resonates powerfully in our current socio-political context.

Radha’s canonical exclusion resonates powerfully in our current socio-political context. As Hindu nationalist discourse elevates certain feminine ideals, particularly Sita’s model of self-sacrificing devotion to define “authentic” Indian womanhood, understanding how religious canons excluded more autonomous female models becomes an act of feminist resistance.

Religious narratives continue to be weaponised to restrict women’s autonomy in contemporary India, making historical analysis of exclusions directly relevant to present struggles.

The erasure of Radha reveals the deep historical roots of contemporary efforts to control women’s sexuality through religious authority. By exposing the deliberate patriarchal strategies that excluded Radha from canon, we gain insight into how similar strategies continue to marginalise women who defy patriarchal expectations in modern India. Recognising these patterns allows us to question them rather than accepting them as timeless religious truths.

Radha continues to stand tall as a rare gem amidst love sagas from across the world. Though institutional authorities attempted to silence her, her appeal was too powerful to eliminate entirely. In the systematic exclusion of Radha, we see not just an ancient patriarchal strategy but the template for ongoing attempts to control female agency through selective storytelling.

Her eventual inclusion in mainstream Hinduism represents a victory of female agency over patriarchal control, showing how even the most determined efforts to erase autonomous female desire ultimately cannot succeed when that desire speaks to something fundamental in the human experience.

References:

- Archer, W.G. Love Songs of Vidyāpati. Routledge, 23 June 2021.

- Gokhale, Namita, and Malashri Lal. Finding Radha. Penguin Random House India Private Limited, 10 Dec. 2018.

- John Stratton Hawley, and Donna Marie Wulff. The Divine Consort. Motilal

- Banarasidass Publishers Private Limited, 1984.

- Muddu Paḷani. The Appeasement of Radhika. Penguin Books India, 2011.

About the author(s)

Writer. Educator. Student. Public Speaking Trainer.

Amazing

Lol what a verbose piece of crap. Please tell in next segment how Muhammad’s marriage to a 6-year old girl smashed patriarchy. Hai himmat Kabra?