In the heart of Kolkata, just near the Gariahat crossing, stands a college bustling with young women from all over the city and beyond. Many of them rush through the gates every morning, unaware that the name above them—Basanti Devi College—belongs to a woman who once shook colonial rule by simply walking the streets.

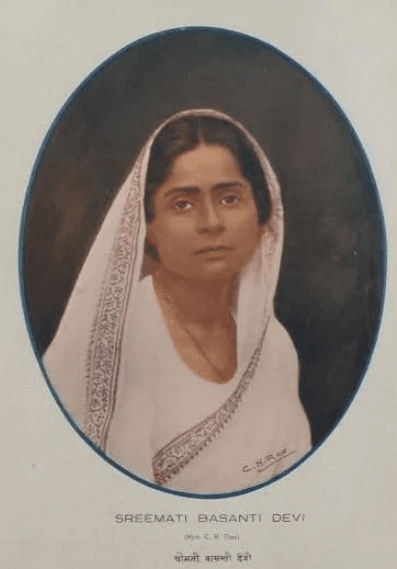

Basanti Devi Das (1880–1974), known by many as the wife of nationalist leader Chittaranjan Das, was far more than just a partner to a political visionary. She was a revolutionary, a rebel in her own right—the first Indian woman to be jailed in the freedom struggle, a powerful supporter of women’s political participation, and a pillar of quiet strength in India’s pathway to independence.

A childhood of comfort, a life of conviction

Born on 23rd March 1880, Basanti Devi grew up in an upper-caste, upper-class household. Her father, Baradanath Haldar, served as the Diwan of a large zamindari in Assam. She was educated at Loreto House in Kolkata, which was a privilege for a girl at that time. At just 17, she was married to a young barrister named Chittaranjan Das—a man who would later become one of Bengal’s most zealous nationalist leaders.

Basanti Devi lived what many might have considered an ideal life for a decade—managing a wealthy household and raising three children. However, when her husband left his law career to join the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1920, the family’s life changed drastically. The income stopped. Comfort gave way to cause. And Basanti Devi stepped into a new chapter—not as a homemaker, but as a revolutionary.

Her arrest that ignited a city

In December 1921, during the height of Gandhi’s Swadeshi movement, Congress volunteers were mobilising to boycott British goods and promote khadi, the hand-spun cloth symbolic of Indian resistance. Chittaranjan Das had an idea that would challenge more than just the colonial administration—he asked Basanti Devi to lead a group of women selling khadi on Kolkata’s streets.

The move was a bold and dangerous one, so much so that even a young political organiser, Subhash Chandra Bose, warned her, concerned about her safety. But Basanti Devi, being the rebel she was, stepped out anyway along with her sisters-in-law Urmila Devi and Sunita Devi and was later arrested by the British for the same. The impact of her arrest turned out to be rapid and violent, even though she was released by midnight.

Kolkata erupted in protest and people from all communities and walks of life united in rage and admiration. The jailing of a high-society Bengali woman for selling khadi became a symbol of courage and resistance. The city’s youth offered themselves up for arrest in solidarity. Her quiet strength even astonished colonial officers.

Basanti Devi Das was more than just a wife

Basanti Devi’s arrest did not mark the end of her activism—it marked its beginning. Days after her husband’s imprisonment, she assumed control of Bangalar Katha, the weekly publication of the Congress.

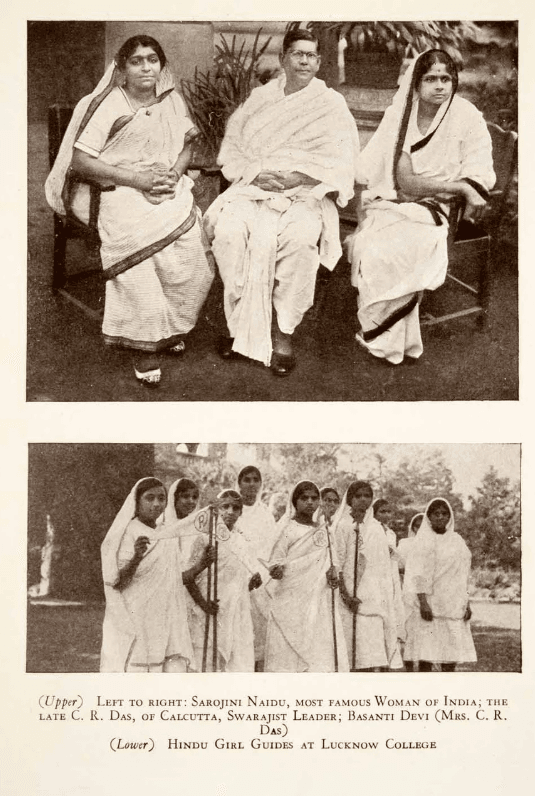

In 1922, she was elected President of the Bengal Provincial Congress, a rare achievement for a woman at that time. Marking a strong achievement yet again, she also addressed the Chittagong Conference the same year and gave a speech that inspired many grassroots agitations and encouraged mass participation. And she didn’t stop there.

With Urmila and Sunita, in 1921, she established the Nari Karma Mandir—a training centre for women activists, a revolutionary idea in an era when women’s political visibility was still minimal. Her activism wasn’t just political—it was cultural, too. Travelling across India, she supported art and cultural development as a way to resist colonial suppression of Indian identity.

The personal cost of public struggle

In 1925, tragedy struck Devi hard when her husband, Chittaranjan Das, died suddenly at the age of 55. And to add to her misery, a year later their son Chiranjeet also passed away. These losses close to her heart deeply shook Basanti Devi. In the letter Mahatma Gandhi wrote to her in 1926, he tried to console her, writing from Sabarmati: “When I think about poor Sujata and you, the whole picture of sorrow rises before me… I can only hope your innate bravery is not only keeping you up but is proving a tower of strength…”

From then on, she withdrew from frontline politics, though she remained involved in social welfare work. She continued the work she believed in quietly, all away from the spotlight. She went against caste norms while arranging for her daughter’s marriage and also stayed in touch with the organisations her husband had found.

Basanti Devi, matriarch of the movement

To Subhas Chandra Bose, Basanti Devi was more than a comrade-in-arms—he saw her as a second mother. After the death of Chittaranjan Das, Bose often turned to her for political and personal advice. In his writings, he described her as one of the four most influential women in his life. To Subhas Chandra Bose, Basanti Devi was not just a freedom fighter—she was a guiding force. After the death of Chittaranjan Das, Bose—who had looked up to Das as a mentor—found a maternal figure in Basanti Devi. In moments of doubt, both personal and political, he would confide in her. She was among the four most influential women in his life, alongside his mother, Prabhabati, his sister-in-law Bibhabati, and his companion Emilie Schenkl. She gave him not just advice but anchoring—reminding him of the freedom movement’s emotional, cultural, and ethical core. It is perhaps telling that a man known for his boldness and action found comfort in the wisdom and quiet clarity of Basanti Devi. Her home remained a space of warmth and guidance for young nationalists. And her voice, though softer now, never truly fell silent.

A name that lives on

After independence, Basanti Devi continued with social work, staying away from politics but never from public service. In 1959, Basanti Devi College was founded in Kolkata—the first government-funded women’s college in the city, named after her.

Even then, she remained deeply involved in the cultural life of Bengal. She was known to attend poetry readings, visit art exhibitions, and support young girls’ education in local neighbourhoods. She is also remembered for encouraging the publication of a revolutionary poem by Kazi Nazrul Islam at a time when few dared to. In 1973, just a year before her death, she was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second-highest civilian award. She passed away on 7th May 1974, at the age of 94.

Feminism and resistance

Gandhiji, Nehru and Bose often dominate our books and knowledge of Indian history of independence but these movements are not built by men alone. They are shaped and carried forward by women like Basanti Devi—who dared to walk out of their homes, face police batons, edit journals, give speeches, defy caste rules, and train other women to join the fight.

Basanti Devi’s life shows us that the fight for freedom and the fight for women’s rights often went hand in hand. She didn’t just step out to protest against the British—she also stepped out of the limits that society placed on women at that time. By doing this, she showed that being a good mother, wife or daughter didn’t have to stop someone from being a brave, outspoken citizen. This kind of activism, rooted in daily life and cultural identity, challenged both colonial rule and patriarchal expectations. It laid the groundwork for a uniquely Indian feminist tradition—one that spoke in many languages, wore many clothes, and took many forms. In remembering Basanti Devi, we don’t just honour a freedom fighter—we honour one of the early architects of feminism in the Global South.

Basanti Devi might not have led armies or governed states but she took the bold step to challenge the whole of the British Empire by selling khadi on the streets of Kolkata, which is as revolutionary as it can get. She wasn’t just Chittaranjan Das’s wife. She was a patriot. A pioneer. A rebel in a sari.

About the author(s)

Anushka Bharadwaj is a journalism graduate from SCMC Pune. She is an intersectional feminist with a deep interest in gender, caste, politics, and mental health. When she’s not writing or reading, she’s usually found lost in poetry, dancing to her favourite songs, or discovering new music—always reflecting on the world through stories.