Language is more than just a tool of communication—it is a living repository of history, culture, and identity. In a time when language is also being used as a battleground for politics, the recent Supreme Court verdict affirming Urdu’s rightful place in India came as a landmark judgment.

The controversy began with a complaint citing a signboard in Maharashtra’s Akola district which featured both Marathi and Urdu writing.

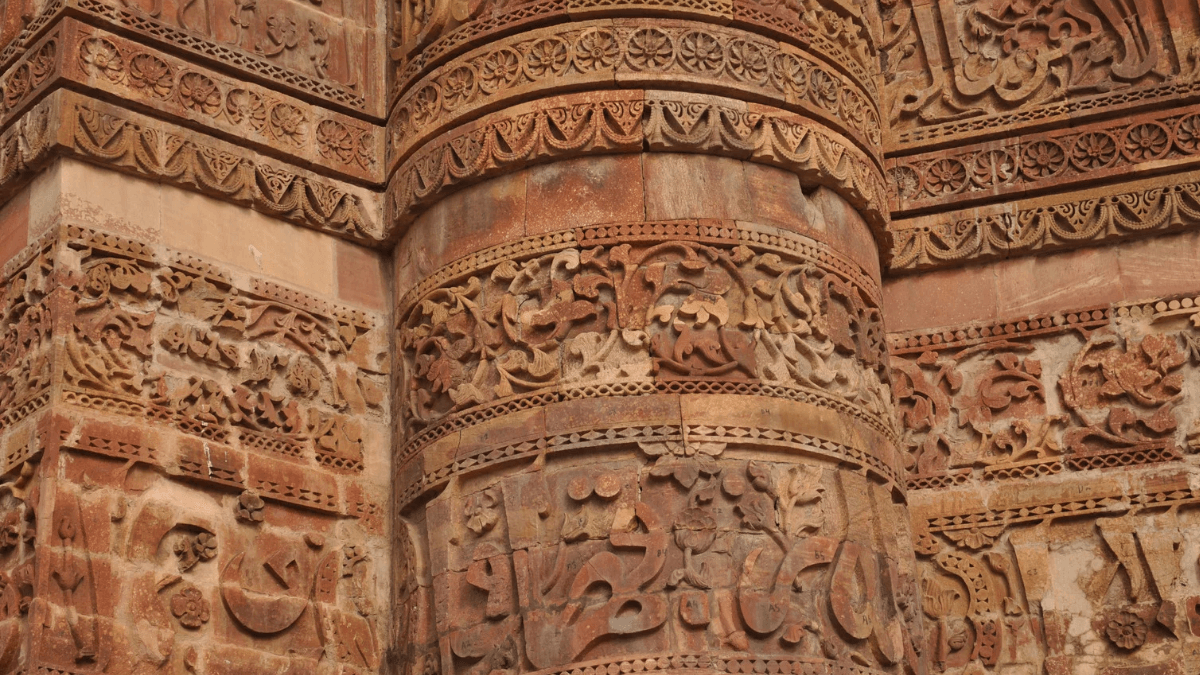

Refusing to give in to the pressures of identity politics, the country’s highest court reaffirmed Urdu’s status as a constitutionally recognised language, describing it as the ‘finest specimen of Ganga-Jamuna tazheeb‘ and a reflection of the ‘composite cultural ethos of the plains of northern and central India.’

But what led to such a complaint being filed in the first place?

Misconceptions faced by Urdu

Despite originating in India and flourishing in the subcontinent for centuries, Urdu has become a victim of misconception—including being considered a foreign or an alien language.

Urdu’s mischaracterisation as an alien language largely comes from its association with Muslims. Attributing a religion to any language is fundamentally wrong because languages evolve within regions, cultures, and communities—not religions. Languages share a large historical base and can’t be confined to a single religion, just as Hindi can’t be solely linked to Hindus and is shared by people across religions.

Labelling Urdu as foreign would also mean insulting Hindi because both languages share an inseparable history—they share a single point of origin, a common grammatical structure, and derive their vocabulary from the same Sanskrit and Prakrit base. Hindi and Urdu are inextricably linked and considered registers of the same language known as Hindustani.

Hindi and Urdu are inextricably linked and considered registers of the same language known as Hindustani.

Urdu is an Indo-Aryan language like Marathi and Hindi. It is as Indian as any other language of the country, and calling it foreign would also mean attacking the cultural pluralism of India.

Origin and historical background of Urdu in India

Urdu originated in the Meerut division of Uttar Pradesh and was part of Hindustani—a culmination of Hindi and Urdu—which was the lingua franca of Northern India pre-independence.

The origin of Hindustani is traced back to the 13th Century, with its words largely derived from languages such as Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic. Even until the late 19th century, Hindi and Urdu were still not bifurcated or recognised as being two distinct languages.

Urdu was widely spoken by Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims alike. Some of Urdu’s most celebrated poets and writers were Non-Muslims such as Munshi Premchand, Kanahiya Lal Kapoor and Pandit Ratan Nath Sarshar.

Hindi and Urdu are still deeply interconnected to the point where many linguists and literary scholars don’t categorise them as separate languages. One cannot speak either of the languages without invariably using words from the other.

Past and present attempts at politicising Urdu

Till the pre-independence era, there was little to no distinction between the languages and both were collectively used under Hindustani to rally people against the colonial powers. The distinction slowly started taking shape during the colonial reign, when East India Company’s divisive policies started gaining momentum.

The distinction between Urdu and Hindi reached a peak during partition when Urdu came to be wrongly attributed as a Muslim language. This assumption was furthered by Pakistan adopting it as its national language, despite only 9.25% of the population speaking Urdu. In India, Urdu is spoken by less than 1/3rd of the Muslim Population.

Even in Indian states where the language is spoken widely, it continues to face discrimination. Uttar Pradesh has the highest number of Urdu speakers in India, making it the third most spoken language in the state after Hindi and Bhojpuri.

Yet when Samajwadi Party leader Mata Prasad Pandey made the demand for UP state assembly proceedings to be translated to Urdu—since it was previously announced that they would be available in Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Bundeli and English—this was met with vituperative comments from UP CM Yogi Adityanath stating the promotion of Urdu would lead to ‘children becoming maulvis‘ and ‘take the country towards kathmulla-pan‘.

The opposition points out the irony that the Chief Minister regularly uses Urdu words in his speeches such as ‘badnaam‘, ‘gunehgaar‘ and ‘sarkar‘, and still deems it appropriate to make a statement like this against the language— pointing out the attempt to “other” a language that is deeply interwoven into the cultural fabric of the country.

The recent attempts of Hindi Imposition are seen as part of a larger narrative of creating a homogenised identity where outliers are subject to discrimination.

Attempts like this play into the larger narrative the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party is being accused of. The recent attempts of Hindi Imposition are seen as part of a larger narrative of creating a homogenised identity where outliers are subject to discrimination. This, in turn, creates easy targets such as Urdu used to further create a distinction between what is “ours” and what is “theirs”.

States like Uttar Pradesh have also been subject to discriminatory treatment of language where names of places with Urdu origin are changed, Urdu signboards at government buildings and railway stations are taken down, despite the state having a large population of Urdu speakers.

In 2023, a circular issued by the Delhi Police Commissioner instructed police staff not to use Urdu and Persian words in official work. A list of 383 words to be avoided was prepared, along with their alternatives in Hindi and English.

The decline of Urdu

The decline of Urdu has been seen since independence, and discriminatory policies have only furthered this decline.

Urdu is being deprived of resources, with Urdu-medium schools and colleges slowly fazed out of government funding and being deprived of infrastructure. Thousands of posts for language teachers remain vacant.

Delhi’s Urdu Bazar is a testament to the decline of Urdu Literature which had once been the hub of Delhi’s literary scene. A place once buzzing with over 80 Urdu bookstores, filled with enthusiastic readers of literature and poetry, and famed poets now stands deserted, with a mere 6 bookstores that also struggle to sustain themselves.

Growing popularity and attempts at revival

Many point out that the language is experiencing a cultural revival, where interest in the language is seen growing.

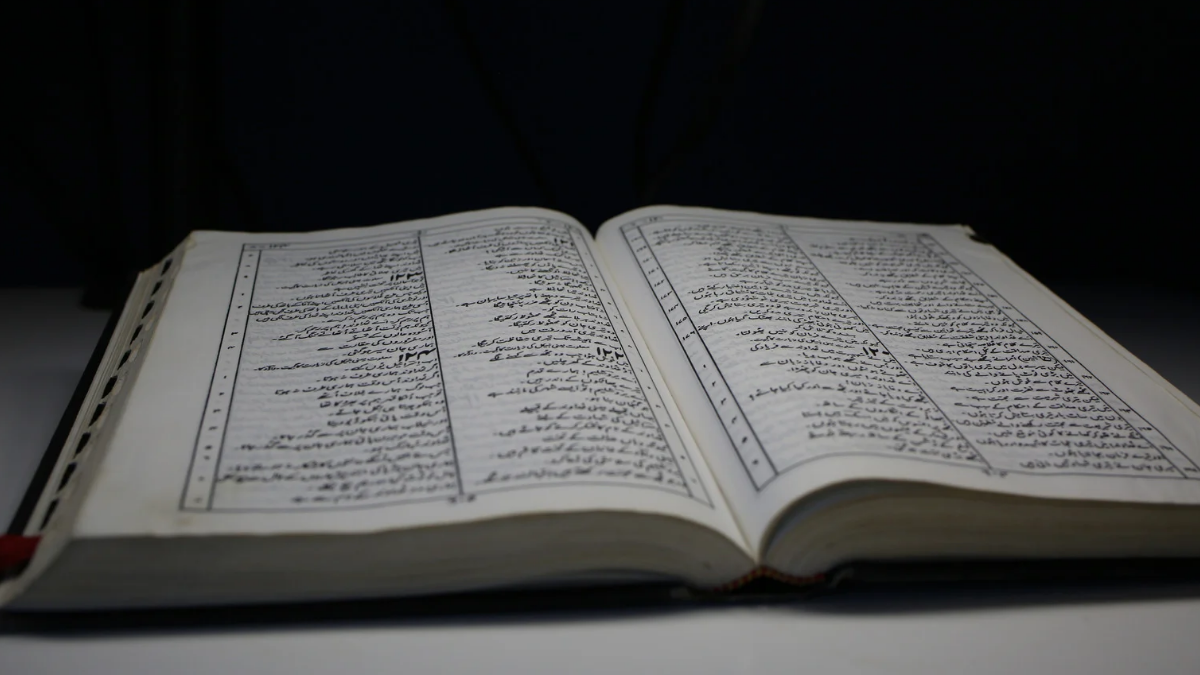

Platforms such as Rekhta started attempting to conserve Urdu literature and poetry. Rekhta has quickly grown into the largest online catalog of Urdu Literature with over 2 lakh books and poetry from over 5000 poets. Readers can also access these works in Devanagari and Roman script and easily look up unfamiliar words in the in-app dictionary.

The growing interest in the language is also reflected by people wanting to learn it formally through language courses.

Many members of the South Asian diaspora have also shown an interest in the language by joining online Urdu learning courses and wanting to teach the language to their kids.

Offline programs have also been accredited creating interest in the language among youth with programs such as Jashn-e-Rekhta.

The program was first held in 2015 and has steadily grown in popularity over the years, with recent editions seeing record-breaking crowds.

The program was first held in 2015 and has steadily grown in popularity over the years, with recent editions seeing record-breaking crowds. Hailed as the world’s largest Urdu literary festival, showcases include ghazals, poetry, qawwali, music, panel discussions and calligraphy workshops.

Linguists such as Rizwan Ahmad have a different view on the festival being linked to Urdu’s revival, ‘The attendance at a Jashn festival or a mushaira or a qawwali is not an indicator of the revival of a language.’ He believes Urdu has become increasingly marginalised over the years, citing the growing trend of Urdu books being printed only in the Devanagari script, ‘as a response to the lack of proficiency in the script among the younger generation of speakers.‘

Celebrated Urdu poet Gulzar refutes this view and believes that the decline in the script doesn’t indicate a decline in the language. ‘The language itself is still alive as it always was…Urdu and Hindi are essentially the same language. It is the script that keeps varying—sometimes Devanagari, sometimes Urdu.’

Gulzar also advocates for an open-minded approach to language evolution, allowing Urdu to adapt naturally over time, much like other Indian languages.

What the future of the language holds

While there has been a decline in Urdu, many people remain optimistic about the resilience of the language. The fear of the decline of the language has been seen in writing as old as 1857 when the politicisation of the language began to take shape. All these years later, Urdu still remains.

The language has, of course, evolved. The Urdu of the 18th-century Mughal court is quite different from the Urdu of the 21st century. This is a testament to the adaptability of the language, which has helped it survive. As society changes, languages change with it. It is often those languages that remain in their purest forms, like Latin or Sanskrit, that face the risk of extinction.

As society changes, languages change with it. It is often those languages that remain in their purest forms, like Latin or Sanskrit, that face the risk of extinction.

Urdu has a rich cultural history that will always keep it alive, be it the shared cultural memory of the independence struggle, the timeless poetry of Ghalib and Faiz, or the melodies and dialogues written in the classical period of Indian cinema.

This language is an essential part of India’s rich cultural history and heritage. Its loss would also mean the erasure of a shared cultural memory that has connected Indians over centuries.

The language’s decline is not just a byproduct of modernisation but of marginalisation. Reviving it would mean allocating enough resources towards it, making it more accessible to younger generations, and fighting against attempts to politicise the language.

The future of the language is uncertain, but not hopeless. Every language goes through a change, and it affirms its status as a living and breathing language. Urdu is going through such a revival—with continued interest and effort, it’s likely to grow stronger in the years ahead.