On June 1 2025, Madrasi Camp, located in Jangpura, South Delhi, and situated directly on the banks of the Barapullah drain, was demolished under the Delhi High Court’s order. It was home to 370 Tamil-origin families who had been living there for more than 50 years. The camp was demolished due to rising concerns over the flood risks before the monsoon, as the water was obstructed by an unauthorised settlement of Madrasi Camp. Delhi’s Chief Minister, Rekha Gupta, also spoke to news channels saying that ‘No one can defy court orders. Residents of that camp have been allotted houses and shifted.’ Despite the government claims that all the displaced residents were shifted to Narela for rehabilitation, only 189 residents were allotted the flats in the area out of a total 370 affected households. Later, 26 families were allotted houses, which left 155 families ineligible for allocation and hence were left homeless.

Residents’ resistance

This incident left behind many pressing questions. Rather than viewing the demolition only as an act of environmental protection or as a routine removal of an “unauthorised colony,” it is important to uncover the deeper stories of building shelter from scratch to collect the shattered remnants of what once made a home. Looking at how different stakeholders are involved in the process, including residents, political parties, and the court, and asking the critical questions: Is demolition inevitable even after residents have lived there for more than 50 years? How does the act of demolition misrecognise residents’ contributions to building and sustaining the city as labourers, domestic helpers, and daily wage earners? And what does life look like after demolition?

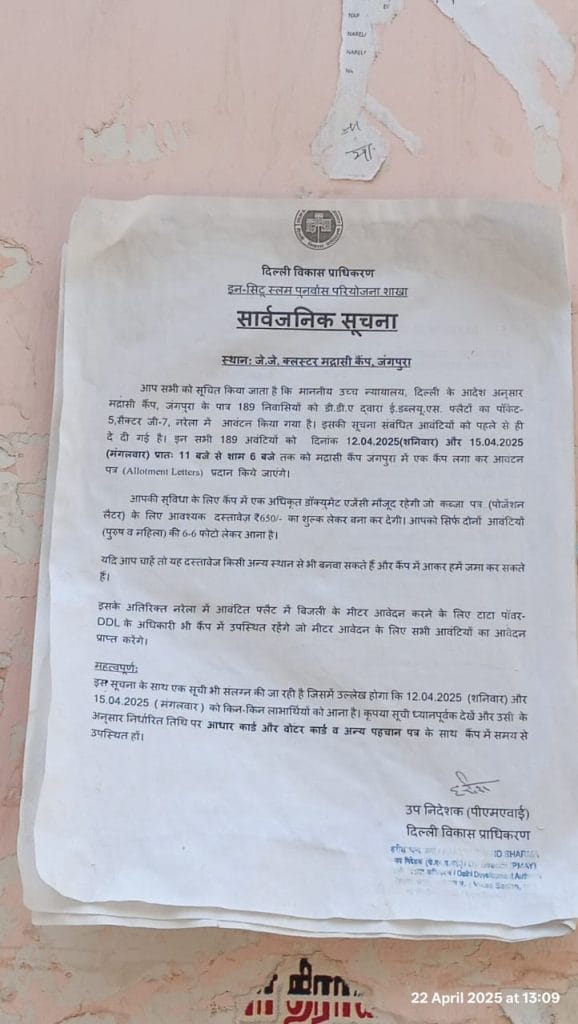

During our first visit to the Madrasi Camp on 22nd April, unaware of the situation of demolition, a group of police officers approached. One of them asked what we were doing there, followed by an instinctive response that we were from an NGO. Moments Later, the camp’s Pradhan (community leader) approached and explained the reason for the heightened tension. He said: ‘Humare logo ko pakad kr le gye hai Narela thane me’ (They detained our people and took them to the Narela police station). This shows the residents’ struggle to stop the demolition and their resistance against the process that can encroach on their livelihood.

The Pradhan also said: ‘Mera teen generation ho gya idhar’ ‘betiyo ka bhi shadi yahi se kiya, unka bhi bacha ho gya, aur ab kehte khali kro’ (Three generations of my family have lived here. We got our daughters married from here, and even they have children now, and now they’re telling us to vacate). Another resident from the camp told me, ‘Humre pass “Modi ka Guarantee Hai”’ (We have Modi’s guarantee).

In order to save their livelihood and home, they took leave from their work, and were detained by the police. The Pradhan also said: ‘Mera teen generation ho gya idhar’ ‘betiyo ka bhi shadi yahi se kiya, unka bhi bacha ho gya, aur ab kehte khali kro’ (Three generations of my family have lived here. We got our daughters married from here, and even they have children now, and now they’re telling us to vacate). Another resident from the camp told me, ‘Humre pass “Modi ka Guarantee Hai”’ (We have Modi’s guarantee).

He was referring to the card that was given during the 2024 election campaign 2024 by a BJP member, where it was written ‘Jaha Jugghi Wahi Makan’, meaning that people’s temporary houses will be considered their own house, through the process of legalisation of illegal houses. This visit to the Madrasi Camp before the demolition shows the residents were determined, agitated, and resistant to the demolition, but at the same time, they had faith in promises that were given in the form of documents like the ‘Jaha Jugghi Wahi Makan’ document by the government, especially during the election campaign.

A state of exception: 50 years of political promises

A camp resident reiterated that they have been here since the time of Indira Gandhi. Then why did the state take five decades to demolish the camp? Why was the settlement allowed, visited, supported, and promised homes, especially during elections? Political parties have visited this camp for decades, seeking votes in the name of democracy. They promised homes, rights, and dignity. Slogans like ‘Modi ki Guarantee’ and ‘Jaha Jhuggi, Wahi Makan’ became tools of persuasion.

The tools for persuasion have made the camp a state of exception where the role of the state is deployed differently. This is not a space where ‘normal laws’ are applied, and the suspension of laws remains silent over the decades. It is the city’s upper and middle classes and the state itself that strategically rely on these settlements: the former as a source of cheap daily labour, and the latter as a vote bank. Hence, the Madrasi Camp and the residents of the camp were always in limbo, where they incrementally auto-constructed their houses without any help or assistance from the formal way of planning the city, but through constant negotiation with the state during elections.

The residents of Madrasi Camp have been deprived not only of their homes but also of their livelihoods. As one of the camp residents said, ‘Hum sab ass pass kaam krte hai, waha jane se kaam chala gye, to fir kya krenge’

There is no binary of formal and informal, but spaces like Madrasi Camps work on the transversal logic of both formal and informal. This state of exception creates a way for peripheral urbanisation, but courts and the state often misrecognise their mode of producing the space, memories, and histories that are razed under the JCB’s bulldozer. The question remains: Is this merely urban planning? Or is it a deeper deception where legality is selectively invoked, and people are punished for surviving?

The cost of demolition

Evidently, the residents of Madrasi Camp have been deprived not only of their homes but also of their livelihoods. As one of the camp residents said, ‘Hum sab ass pass kaam krte hai, waha jane se kaam chala gye, to fir kya krenge’ (We all work nearby. If we are sent there, we’ll lose our jobs—what will we do then?). Here, the understanding of the residents about the deprivation caused by the demolition is not only about the shelter, but that their legal right to work will also be deprived. For them, shelter and work are integrated.

Right to livelihood – a constitutional betrayal

As mentioned in the judgment of the Olga Tellis case of 1985, the Supreme Court, in response to a PIL against huts and settlements on pavements, held that ‘The eviction will deprive them of their fundamental rights, that is, the right to livelihood in Article 21, and it is impermissible to call them trespasses, because there are economic compulsions behind their settlement.’ The Court has interpreted the right to life in a wider context where the right to life is not limited to just taking life but to what makes life meaningful, and what makes life liveable, and what the means of life are, that is, livelihood.

The right to livelihood is an integral component of Article 21. Even the state’s responsibility to make life liveable is enshrined in Article 39(a) and 41 of the Constitution, which talk about the right to work. In this light, the demolition of Madrasi Camp, even if justified on the grounds of environmental protection, raises concerns that if it results in the deprivation of the residents’ livelihoods without adequate rehabilitation or alternatives, it can be seen as an infringement of the very constitutional protections that the Court is bound to uphold.

After the bulldozers: Re-unsettling in Narela

The resettling of camp dwellers into Narela is not what it is; really, the resettling, but it’s re-unsettling. Due to the distance from the settlement and workplace, and the lack of facilities and inadequate living environment, they often resettle in other slums and camps to live. So, the process of resettlement is not actually to resettle but to re-settle into different camps and slums.