The Supreme Court in April 2025 issued a new set of guidelines and directions for the centre and all state governments to prevent child trafficking and heinous offences related to it. The court ruled that ‘any laxity in implementing the directions would be taken seriously and be treated as contempt of court.’ The bench led by Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan, strongly criticized the Allahabad High Court’s “callous” handling of bail applications in a child trafficking case, observing that several accused were repeat offenders. The apex court urged the courts to complete the trial within six months and directed the states to adopt stringent measures to prevent such crimes. The judgment also reaffirmed the constitutional protection of life and liberty under Article 21. It invoked Sections 370 and 370A Indian Penal Code (now Sections 143 and 144 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita) to address trafficking and exploitation.

Major legal victory in preventing child trafficking

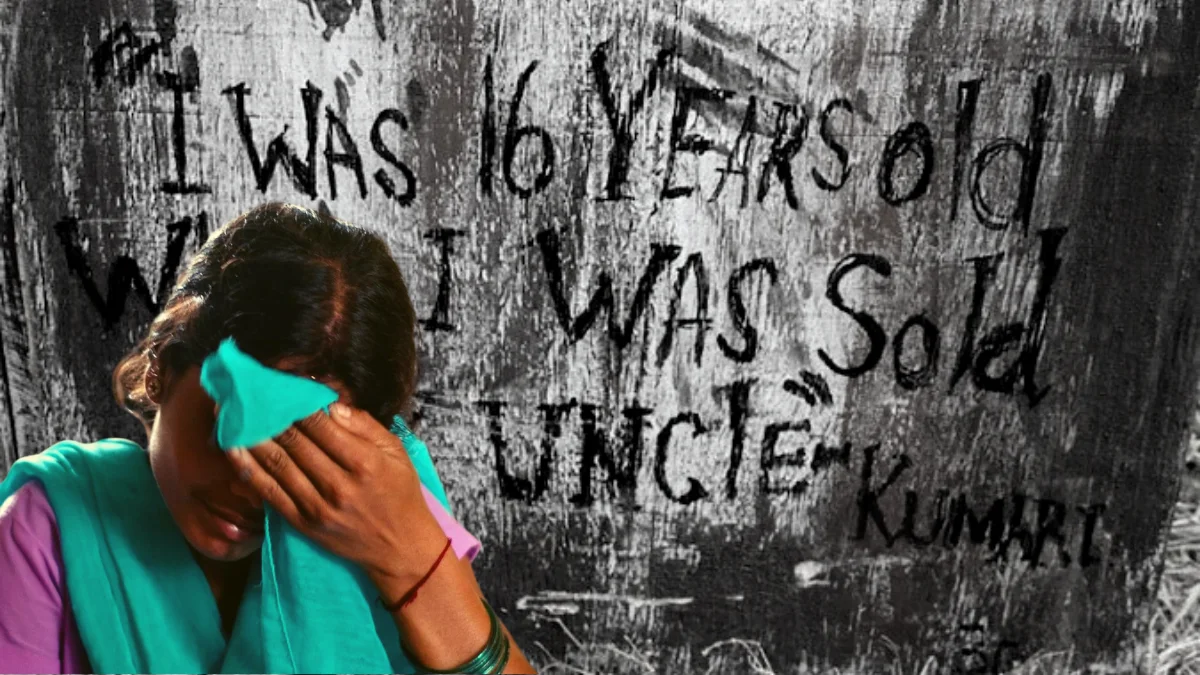

Pinki vs State of Uttar Pradesh, 2025 is a significant legal victory towards the protection of children and prevention of child trafficking given the recent surge of such crimes in the country. The case was brought against an interstate child trafficking racket in Uttar Pradesh that targeted impoverished children. Thirteen accused were arrested in connection with the offence of abducting the children and selling them for illegal adoption. While the case was pending for committal to the sessions court, the Allahabad High Court granted bail to the accused. As a result, several accused absconded and threatened the families. This necessitated the victim’s family members to file a special leave to appeal before the Supreme Court.

In this case of interstate child trafficking, street-connected children were targeted by well-organized traffickers, involving a series of deliberate acts of kidnapping, and subsequent sale of minors at prices ranging from ₹2 lakh to ₹10 lakh per child. Functioning as a coordinated network, their modus operandi was exploiting digital technology to disseminate images of the victim children, identify the prospective buyers, share location, and facilitate fund transfer.

Around 12:30 PM on April 9, 2023, Pinki, a ragpicker, discovered that her 1-year-old son, Bhahubali, who was sleeping beside her, had gone missing. Following the missing person complaint filed by Pinki, initial investigations commenced with the examination of CCTV footage from the area. Further investigation revealed that the abduction and trafficking was conducted systematically over months.

Around 12:30 PM on April 9, 2023, Pinki, a ragpicker, discovered that her 1-year-old son, Bhahubali, who was sleeping beside her, had gone missing. Following the missing person complaint filed by Pinki, initial investigations commenced with the examination of CCTV footage from the area. Further investigation revealed that the abduction and trafficking was conducted systematically over months, with the racket having kidnapped and illegally sold 19 other impoverished children.

The investigation and search operation across Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, and Jharkhand aimed to recover the kidnapped children and arrest the gang members. Each child was located within the residence or custody of one or another of the accused persons. Chargesheets were lodged before the Special Chief Judicial Magistrate, Varanasi; bail was subsequently granted by the Allahabad High Court while the committal proceedings before the Court of Sessions remain ongoing.

Consequently, relatives of the rescued children filed multiple special leave petitions in the Supreme Court, challenging the High Court’s bail orders under Sections 363 (Kidnapping from Lawful Guardianship), 370 (Trafficking of Persons), and 370A (Exploitation of Trafficked Persons) of the Indian Penal Code (now Sections 143 and 144 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita), and invoking Article 21 of the Constitution. They argued that the High Court failed to consider the seriousness of the offense, the organized nature of the trafficking network, and the vulnerability of the victims. Recognizing the commonality of the accused and the nature of the alleged offense, the Supreme Court directed that all petitions be consolidated for joint consideration.

Allahabad high court decision

Relying on the principle that “bail is the rule and jail is the exception,” the High Court granted bail to the 13 accused, citing specific reasons for its decision. These included the absence of the accused’s names in the original First Information Report (FIR), their arrest based solely on statements from co-accused during custodial interrogation, and the lack of direct recovery of victim children from the accused or immediate linkage to the crime.

However, bail was granted subject to strict conditions: the accused must not interfere with prosecution evidence or exert influence over witnesses. Additionally, the court mandated the accused’s attendance before the trial court on the scheduled date and prohibited any form of inducement or threat to witnesses.

Supreme court review

A two-judge bench comprising Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan overturned the bail grant and sharply criticized the Allahabad High Court’s handling of the matter as “very callous.” The Supreme Court underscored the High Court’s failure to account for the offense’s seriousness, the systemic nature of the trafficking network, and the overriding public interest. It observed that child trafficking inflicts enduring suffering on parents, “worse than death,” as they endure perpetual anguish unlike those grieving natural loss. Emphasizing that several accused were repeat offenders, the Court held that bail was unwarranted and ordered its revocation. In addition to annulling the bail orders, the Court issued a comprehensive set of procedural directions to ensure expeditious handling of trafficking cases.

Court’s directives and guidelines

The Court directed the committal of all three trafficking-related criminal cases in Varanasi to the Sessions Court within two weeks, with charges to be framed within one week of the order. If any accused is absconding, the trial court must secure their presence through non-bailable warrants and conduct separate trials to avoid delays. The court ordered trials to proceed on a priority and preferably day-to-day basis. The Court directed the State Government to appoint three special public prosecutors and ensure police protection for the victims and their families.

It mandated that all child-trafficking cases pending in trial courts be concluded within six months of framing charges. High Courts were directed to compile status reports on such trials, and District Judges were tasked with allocating dedicated courtrooms and judges to this category of offenses. A further instruction required close inter-state coordination among police forces and regular updates to victim families, thereby addressing both systemic delays and fragmented enforcement.

The verdict mandated that all child-trafficking cases pending in trial courts be concluded within six months of framing charges. High Courts were directed to compile status reports on such trials, and District Judges were tasked with allocating dedicated courtrooms and judges to this category of offenses.

Beyond trial-specific measures, the Court mandated the State to ensure educational rehabilitation for the rescued children under the Right to Education Act, 2009, and to provide victim compensation under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023, and relevant welfare schemes. All States were instructed to review and implement the recommendations from the Bharatiya Institute of Research and Development (BIRD) report (dated April 12, 2023), released by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to address human trafficking. High Courts were directed to gather data on pending trafficking trials, issue circulars ensuring expedited trial timelines, and report compliance to the Supreme Court. The court cautioned that non-compliance by any authority would invite strict judicial scrutiny and potential contempt proceedings.

Conclusion and impact

The analysis of the Supreme Court’s ruling reveals a multifaceted, proactive approach. First, the court’s guidelines and directives aim to protect the rights of the children in this case and prevent future instances. Secondly, by deeming the Allahabad High Court’s bail decision flawed, the court underscored the necessity of judicial accountability in the criminal justice system. Thirdly, the court reiterated that a child’s rights are absolute, irrespective of their sex, place of origin, or financial status. Thus, the Supreme Court reaffirmed its constitutional role as protector of fundamental rights, ensuring justice for marginalized groups.