While conditional access to abortion exists in India, the process of seeking one involves navigating the complexities of an institutional and legal system riddled with contradictions and arbitrariness. These challenges severely impact women’s timely and safe access to a critical reproductive healthcare measure.

A new study by the Centre for Health Equity, Law, and Policy (C-HELP) at the Indian Law Society, Pune, found that between 2019 and 2024, Indian court rulings on abortions consisted of inconsistencies, delays, and rights violations. The report titled The Bench and Body: An Analysis of Abortion Jurisprudence in India (2019-2024), examined the judicial landscape of abortion access by analysing 1126 cases adjudicated by the Supreme Court and various high courts.

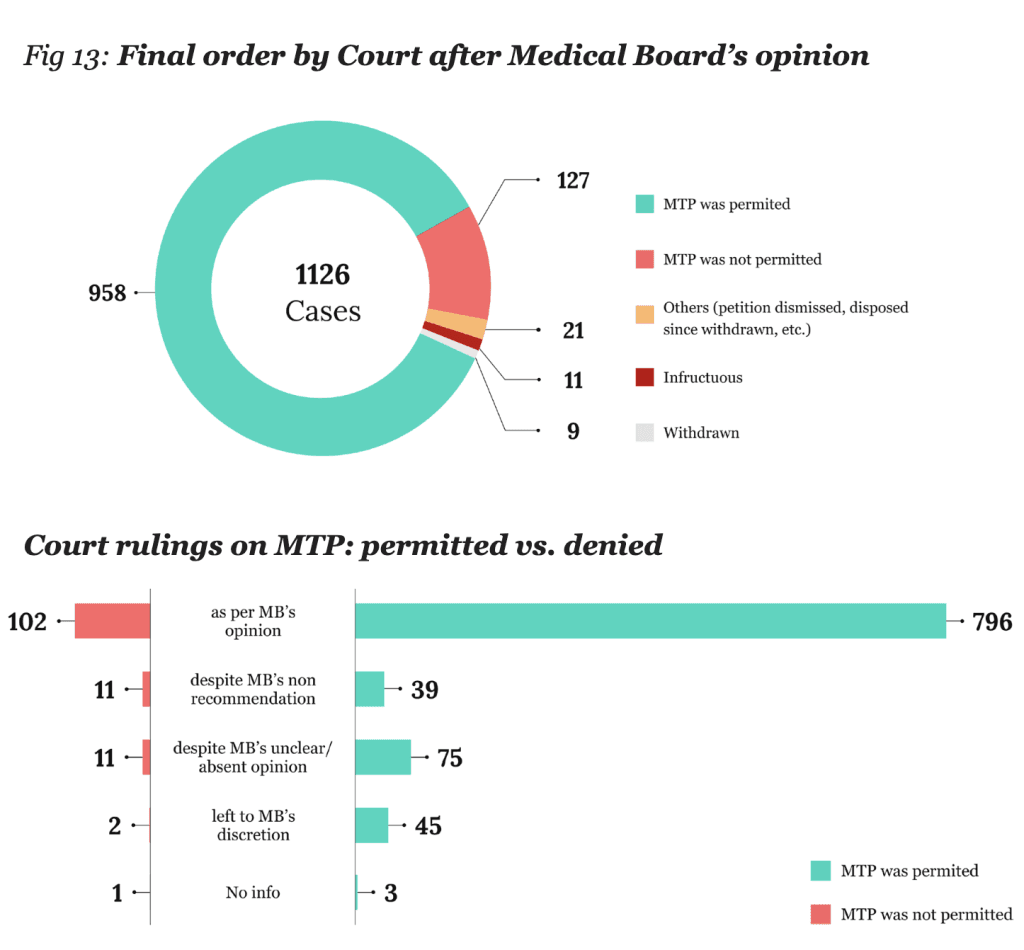

In 85 per cent of these cases, abortions were allowed by the courts. However, a pattern has emerged in which judicial intervention has become the de facto mechanism on which abortion access is predicated, even though the law does not require this. Criminalisation of abortions leads to healthcare providers refusing to perform them without court mandates to avoid the risk of prosecution. This forces women to court, creating barriers to timely and dignified access to reproductive healthcare.

Legal status of abortion in India

The legal landscape of abortions in India is complex, with a gulf existing between de jure and de facto practices. While abortion is criminalised, provisions exist that allow women to seek them under specific circumstances and on certain grounds. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act (MTP), 1971, and its 2021 amendment govern this. All terminations conducted beyond the scope of this Act constitute a crime and are subject to criminal penalties.

The MTP Act doesn’t guarantee the right to abortion; it only extends the option to certain types of pregnancies. Pregnancies may be terminated in cases involving risk to the life, physical health, or mental health of the pregnant woman; severe foetal disabilities; sexual violence; and failure of contraception.

Before the amendment, the gestational cut-off under the Act was 12 weeks with the approval of one registered medical practitioner (RMP) and 20 weeks with the approval of two RMPs. The 2021 amendment increased these limits to 20 and 24 weeks, respectively. Beyond this gestational cut-off, those seeking abortions will have to approach the courts.

Crucial findings in the report

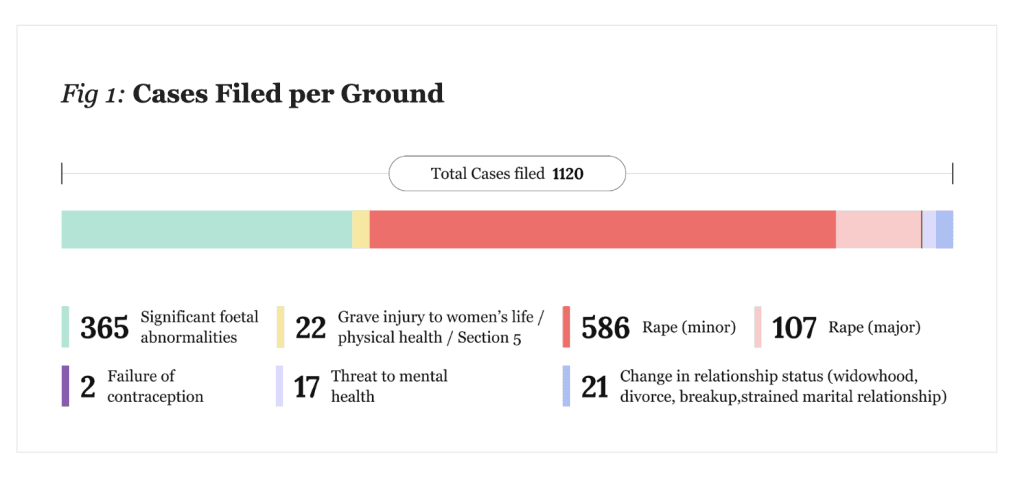

The study found that in 52.04 per cent of cases analysed, judicial intervention to access abortions was sought in cases of sexual violence involving minors. This was followed by grounds of major foetal abnormalities (32.33 per cent) and sexual violence involving adult survivors (9.41 per cent).

Abortion was allowed in 85 per cent of cases, and denied in 11.28 per cent. In 81.89 per cent of these cases where abortion was denied, the court’s decision was based on the opinion of the Medical Board, i.e., 9.23 per cent of cases studied ended in access to abortions being denied by the courts due to the Medical Board’s recommendation.

The study also found that the interpretation and application by courts of the criteria outlined in the MTP Act weren’t consistent. Some benches relied on a rights framework to affirm abortion rights, while others rejected such a rights-based framework in favour of a more rigid reading of the Act or made rulings based on considerations beyond its scope. Even within the same court, including the Supreme Court, inconsistencies exist across benches. Women seeking abortions under similar circumstances were, therefore, met with inconsistent outcomes depending on the approach the bench took.

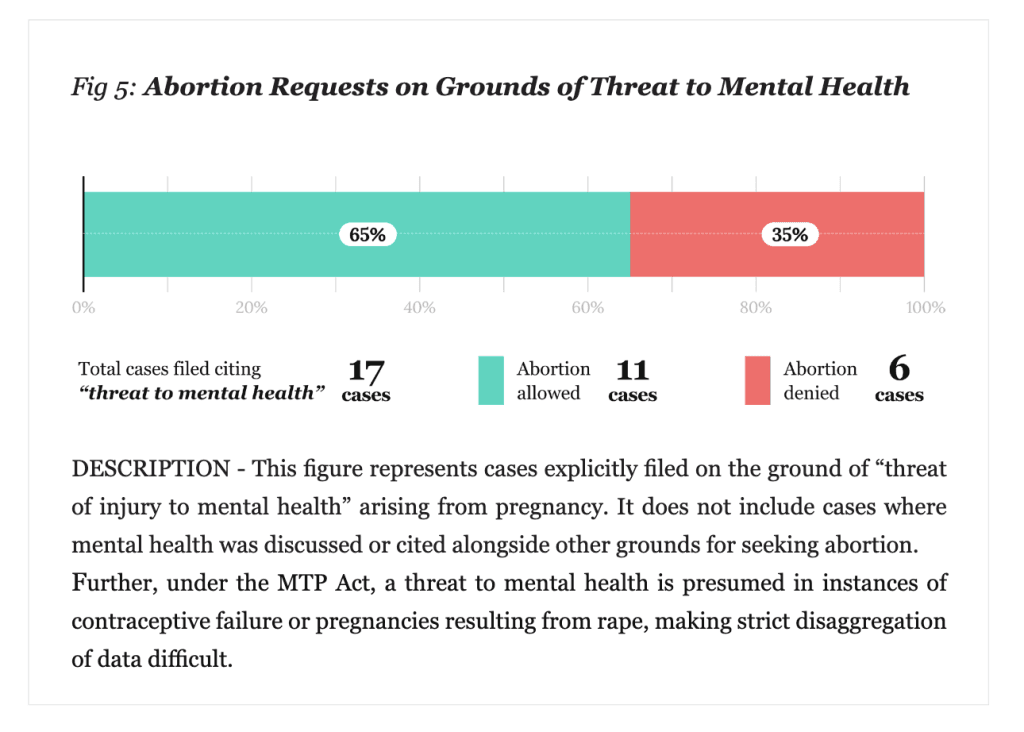

Abortions sought on mental health grounds also saw a narrow understanding of the term in many cases, with courts and Medical Boards requiring a formal diagnosis of mental illness to grant a termination request. However, one of the most critical findings of the study is that several of these cases didn’t require petitioners to approach courts to access abortions as per the MTP Act. These cases fit the criteria set in the Act and were within the gestational window. This was especially true of cases where petitioners were seeking terminations on the grounds of sexual violence.

Barriers for minors seeking abortion

Provisions in the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012, require healthcare providers to report all cases that fall within its ambit to the authorities. Providers, concerned about running afoul of the law, often deny minors abortions without judicial intervention. Further, under the POCSO Act, all sexual activity involving minors, even consensual relationships involving adolescents of the same age, is criminalised.

However, in cases of pregnancies resulting from sexual violence against minor survivors, they are often pushed to approach the courts, even when these pregnancies have not exceeded the gestational limit. Of the cases studied (305) where sexual assault was the grounds for seeking termination of the pregnancy, 234 cases involved minor survivors. While most of these cases saw the petitioner’s request for abortions being granted, making court orders a de facto requirement to terminate the pregnancies of minors creates obstacles in their ability to access abortions in a timely fashion and with relative ease.

Medical Boards

The MTP Act allows for the establishment of permanent and ad hoc Medical Boards. When courts hear abortion pleas, they can constitute an ad hoc Medical Board to provide their expert opinion regarding the impact of continuing the pregnancy on the physical and mental health of the woman and in assessing foetal abnormalities.

However, the report found that in some cases, the Medical Board went beyond the scope of this role and invoked ideas that were moralistic, medically irrelevant, and discordant with provisions of the MTP Act. In 1.60 per cent of cases, the Medical Board recommended against abortions, citing concerns regarding future pregnancies. In five cases among them, courts denied abortions solely over this concern expressed by the Medical Board.

In Raisa Bi vs State of Madhya Pradesh (2019), the High Court denied a 13-year-old child, who was a sexual violence survivor, the right to terminate a pregnancy. The Medical Board’s recommendation to the court was that the pregnancy be continued, noting that the child had no major mental illnesses and the pregnancy posed no risk to her life. This recommendation and subsequent court ruling callously dismiss the devastating mental health implications of a childhood pregnancy, especially one that is a product of sexual assault.

Ad-hoc Medical Boards, where open-ended investigation was allowed, disproportionately focused on ‘foetal health’ as well. Moralistic overtones were also noted among members of the Medical Board, as were discussions of foetal viability. The report further noted that Medical Board decisions tended to place increased focus on the foetus, instead of the pregnant woman. There is also opacity in the constitution of Medical Boards, with little to no measures in place for accountability. Nor is there adequate oversight to prevent them from making decisions influenced by their own biases.

Shifting judicial ideas and critical lapses

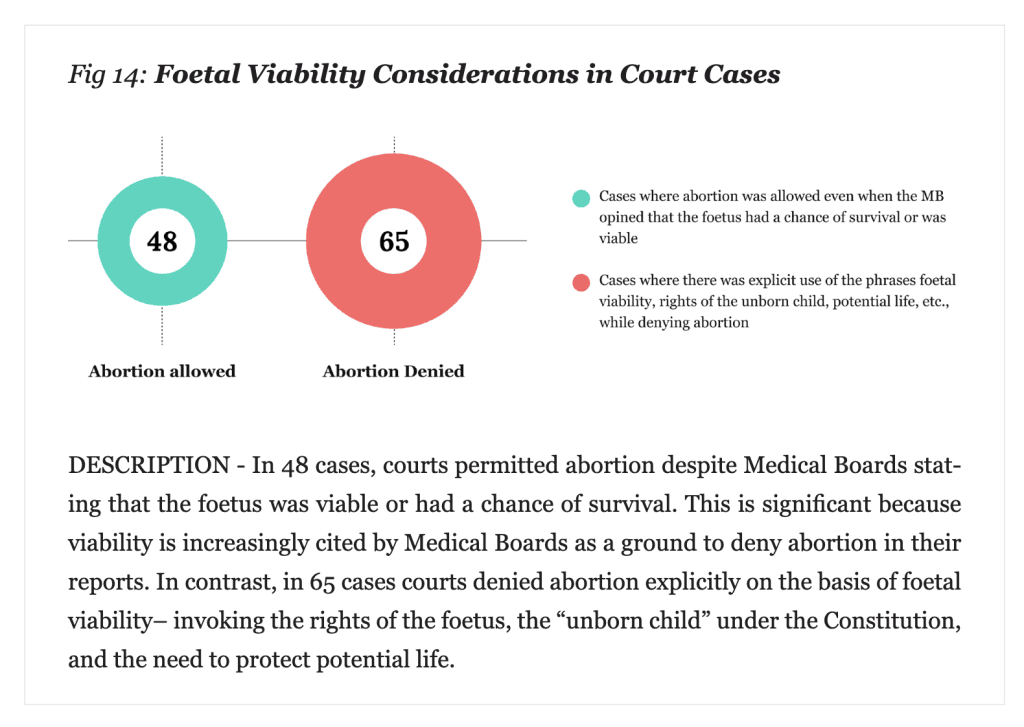

A concerning finding was that in several instances, courts and Medical Boards invoked ideas of foetal viability, a contentious subject in abortion discourse, and one which doesn’t constitute grounds to deny an abortion as per the MTP Act. In 65 cases beyond 24 weeks of gestation where abortion was denied, one of the grounds cited by the bench and Medical Board was the presence of a viable foetus.

In nineteen other cases, notions of foetal personhood, the foetus’s right to life, and its fundamental rights were mentioned. This is a cause for alarm because ideas of foetal viability and personhood are often used to legislate anti-choice measures into existence, like in the case of the United States. Ideas of foetal rights are antithetical to women’s exercise of their reproductive rights and autonomy, and in considering foetal rights when granting or denying abortion requests, courts and Medical Boards are doing so at the cost of the rights, interests, and bodily autonomy and integrity of the pregnant person.

The report also found problematic language used by courts in their rulings, including emotive language, language with paternalistic and moralistic undertones, and language lacking in empathy. In several cases, anatomically incorrect terms were also used by courts in discussing pregnancies. The report also found delays in rulings, with one such delay stretching to three months. Delays push women beyond the gestational limit, which can then be used against them to deny access to abortions.

Another notable finding was that women who were viewed as victims by courts were more likely to receive abortion care as a consequence of paternalism. The report ends with several recommendations, most notably the decriminalisation of abortions and addressing denials by healthcare providers within statutory limits.

One important thing to note here is that this study only analysed abortion access in cases where judicial intervention was sought; it doesn’t paint a comprehensive picture of the abortion access landscape in India. Many of those who are denied abortions don’t pursue the matter to court, and several are forced to turn to unsafe abortions. Approaching courts is a considerable strain on resources and time, precluding the option for many.

While 85 per cent of cases that sought judicial intervention resulted in an abortion, it would be erroneous to extrapolate this data to the larger question of abortion access outside of courts. The situation of abortion access remains bleak; a quagmire of statutory and procedural inadequacies, further exacerbated by socio-institutional patriarchy and stigma. This study is a critical reminder that reproductive healthcare in India suffers from critical inadequacies and needs urgent reform to ensure that all women have easy, timely, and dignified access to abortion healthcare.

About the author(s)