“Power is not merely something that one possesses, but something that one enacts through repeated behaviour“, Judith Butler’s insight from Gender Trouble captures precisely how masculinity operates in the digital age. Today, masculinity is not only shaped at home, in school, or within peer groups, it is constantly constructed and performed online. Instagram comment sections, Reddit threads, YouTube reaction videos, anonymous Telegram groups, short-form meme pages, and influencer communities have become new classrooms where boys learn what it means to be men, or, more accurately, what they are told masculinity should be.

In these digital worlds, one can see how masculinity takes on new textures that are louder, more competitive, more aggressive, and more intolerant of vulnerability. Raewyn Connell, whose work on hegemonic masculinity remains foundational, argues that “masculinity is not what men are, but what they do to maintain power.” And the internet is a vast space where this doing is encouraged, rewarded, and multiplied. Acts of domination and ridicule become not only personal choices but performances that are spectacles of masculinity watched and applauded by thousands.

A meme may simply appear as humorous or clever, but many memes are deeply rooted in sexist, casteist, classist, or homophobic notions, where humour becomes a vehicle for the circulation of hate.

The performance often begins with something seemingly harmless, such as a meme. Meme culture, which has become the primary language of online youth, plays a crucial role in shaping digital masculinities. A meme may simply appear as humorous or clever, but many memes are deeply rooted in sexist, casteist, classist, or homophobic notions, where humour becomes a vehicle for the circulation of hate. When a meme mocks a woman for speaking up about harassment, for wearing certain clothes, for being outspoken, or simply for existing publicly, the humour normalises violence. It tells boys, ‘this is acceptable. This is funny. This is how you talk about women.’

The 2020 Bois Locker Room case is a stark example of how young boys used memes, screenshots, and private chats to sexualise minors, discuss rape, and laugh about it together. These boys were not in their twenties, they were high school students. Some emotions stick because they bind us to others, and in this case, the emotion was mockery, and the binding force was misogyny. The digital world taught these boys that humiliating girls was not harmful, rather, it was considered entertainment.

However, cruelty grows faster when it is shielded by anonymity. One of the most powerful accelerators of digital masculinity is the ability to act without consequences. In anonymous forums, men can express rage, frustration, resentment, and entitlement without revealing themselves and without facing accountability. The result is a hypermasculine performance of harsh words, sexual threats, casteist slurs, and violent fantasies delivered with boldness they would never display offline. This is visible in the daily reality of many women journalists and activists in India.

Amnesty International’s Troll Patrol (2018) found that women of colour receive 34% more abusive messages than white women. In the Indian context, Dalit, Adivasi, and Muslim women face particularly intense forms of online violence, often blending misogyny with casteism and communal hate. Anonymity allows men to treat women not as people but as targets, proving their masculinity through the depth of their cruelty.

The concept of digital masculinity is even more hazardous when it is combined with political ideology. Nationalism and masculinity interlock in the context of India. In 2021, a young climate activist, Disha Ravi, was not attacked solely because of her political position, as she was arrested and charged with distributing a toolkit to aid farmers in protesting. Disha was subjected to gendered insults, character attacks, and sexual implications by online trolls, in which political masculinity was exerting itself on her womanhood. The same trend appears in the incidents involving female journalists, actresses, and activists who, in most instances, are genderedly assaulted in political posts, while their male counterparts speak out without the same kind of harassment. The implication is evident that any form of dissent is considered masculine when it is done by men, deviant when done by women.

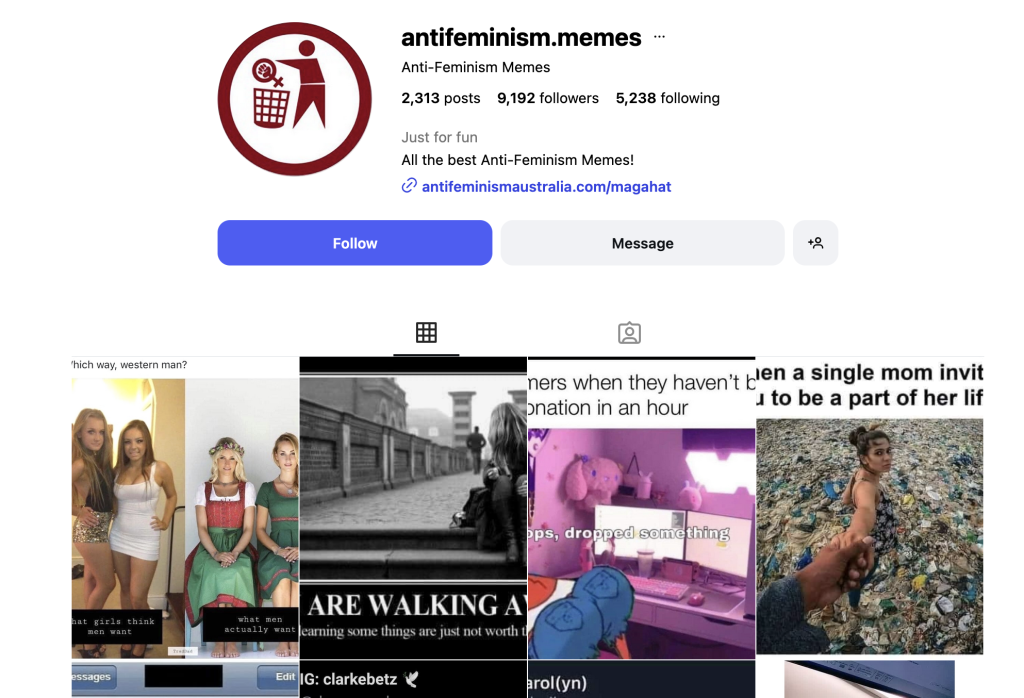

Nevertheless, maybe the most disturbing type of digital masculinity is a result of the development of incels (involuntary celibates), Men’s Rights Groups, and anti-feminist communities. These groups share a common feeling of resentment, a claim, and violence against women. Incels are convinced that sex and love belong to them, and women are indebted to their love. The language of incel circles, violent fantasies, and conspiracy-oriented stories about feminism and female autonomy reeks with misogynistic expressions. India also has Reddit, Telegram, and YouTube spaces for incels. Many teenage boys, who seek validation or a sense of identity, fall into these echo chambers.

Many influencers who preach “alpha male” behaviour, “no mercy” dating advice, and anti-feminist rhetoric gain massive followings, shaping how boys think about relationships, emotions, and women’s autonomy. Men’s Rights Activists add another layer to this hostile environment, while some raise legitimate issues, such as men’s mental health or biased custodial laws, many weaponise these discussions to attack women. They claim that feminists hate men, that women fabricate harassment allegations, and that “modern girls” are ruining society. During the #MeToo movement in India, many men’s rights activists and anti-feminist pages ran campaigns attempting to discredit survivors, often using doxxing, character assassination, or mass-reporting to silence feminist voices.

One of the most powerful accelerators of digital masculinity is the ability to act without consequences. The result is a hypermasculine performance of harsh words, sexual threats, casteist slurs, and violent fantasies delivered with boldness they would never display offline.

Anti-feminist meme pages also play a significant role in shaping digital masculinities. These pages present feminism as a joke, feminists as irrational, and gender equality as a threat to male identity. They promote rigidity, like a man must be strong, unemotional, and dominant. A woman must be submissive or else be mocked. For young boys who consume this content on a daily basis, misogyny becomes not only familiar but desirable. It becomes an integral part of their personality, sense of humour, and online presence. Together, these digital cultures form a machinery of masculinity, a system where hate is not merely expressed but produced, encouraged, refined, and repeated. Every “joke,” every threat, every meme, and every hateful comment becomes a small act in a larger performance of power, and that power is almost always directed downward, toward women, gender minorities, and marginalised communities.

One male user shared how he stopped posting or writing about feminism on social media after receiving waves of hostility, “I used to share content about gender equality, feminism, sexuality etc., but the insults and trolling became unbearable. Men on my feed called me ‘weak’ and ‘simp’ for supporting women. Even my own friends mocked me and said, ‘Real men don’t get emotional.’ I felt cornered and exhausted, so I stopped speaking up. It felt like I had to choose between my beliefs and my mental peace.” Another user reflected on how unlearning patriarchal values feels like swimming against the current, “…when I try to rethink masculinity, every reel, meme, and podcast online says men must be dominant, emotionless, and always in control. The algorithm keeps feeding me alpha-male content, and sometimes I feel pulled back into the same mindset I’m trying to leave.” In contrast, another user described how backlash made him more determined instead of silenced, “When I spoke against misogynistic jokes online, people flooded my inbox with abuse. At first, it shook me, but then I realized how necessary activism is. The hate only showed how deeply change is needed and now I’m building a support network of men who want to reflect and do better instead of staying silent.“

In the end, the narrative around digital masculinity is not a story about boys vs. girls, but it is a story about power, how it moves, how it seduces, how it performs.

Research validates these emotional and psychological impacts. Jane (2014) describes the rising trend of “e-bile”, extreme digital misogyny, showing how online harassment silences voices advocating for gender justice, mirroring the withdrawal feelings from feminist engagement. Ging (2019) highlights that algorithm-driven masculine subcultures such as incel and “alpha-male” spaces act as pedagogies that socialize boys into rigid, emotionally detached masculine norms. Furthermore, Jo et al. (2024) found that backlash can sometimes strengthen activism and foster community-based resistance. Together, these studies show how digital platforms both reproduce toxic masculinities and simultaneously become spaces for counter-narratives and empathetic activism.

We cannot dismantle digital patriarchy using the tools of silence, shame, or individual resilience, because the scale is too large, and the machinery is too well-oiled. What we need is a multi-layered approach, such as feminist digital literacy in schools, emotional education for boys, platform accountability, community support systems, and a cultural shift that allows boys to feel and express vulnerability instead of masking it with aggression.

Digital masculinities are not inevitable. They are constructed meme by meme, comment by comment, algorithm by algorithm. And anything constructed can be deconstructed. The internet is capable of producing hate, but it is also capable of producing care, solidarity, and new, gentler ways of being men. If boys can learn cruelty online, they can also learn compassion. If anonymous forums can amplify hate, communities of accountability can cultivate empathy. The same digital spaces that create harm can also be used to heal, if we choose to reshape them.

In the end, the narrative around digital masculinity is not a story about boys vs. girls, but it is a story about power, how it moves, how it seduces, how it performs. Additionally, it is a narrative about the possibility of reimagining what it means to be a man in a world where traditional scripts are redundant, and the question is whether we are willing to rewrite those scripts, one click at a time.

About the author(s)

Dharanesh Ramesh is a native of Coimbatore and a postgraduate student of Gender and Development Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad. Rooted in the belief that stories shape structures, his study and work explore the intersections of gender, caste, and public policy through an intersectional feminist lens. He is particularly drawn to understanding how power, privilege, and policy weave together to define inclusion and equity in everyday life. Inquisitive by nature, Dharanesh often turns to drawing, painting, photography, and writing as extensions of his reflective practice. His work seeks to bridge thought and experience, analysis and art, in the pursuit of justice and representation.