Cinema based on “real events” has always had a way of revealing not the past, but the anxieties of the present. Haq (2025), Suparn Varma’s fictional re-interpretation of the Shah Bano moment, is no exception. It enters the cultural space at a time when the Indian state is aggressively curating stories about Muslim women—stories of suffering, betrayal, and patriarchal captivity, often framed through a saviour narrative orchestrated by majoritarian politics. Within this landscape, any film that invokes triple talaq, Muslim women’s rights, or the spectre of religious authority must be examined not simply as art but as an intervention. The question is not whether Haq “treats the subject well.” The question an intersectional, radical, postcolonial, and Islamic feminist asks is more uncomfortable: Who gets to tell Muslim women’s stories, and why? Whose patriarchy is being critiqued? Whose power is being consolidated?

And where, in the thick fog of ideological appropriation, does the woman herself actually stand? Varma’s film attempts to craft a feminist parable of a woman demanding her rights, but in doing so, it also participates in a long lineage of cinematic and political narratives that make Muslim women hyper-visible while stripping them of political agency. Yet, despite these complexities, the film creates a character—Shazia Bano—whose journey reveals how the intersections of gender, religion, class, and state power shape the life of a Muslim woman in India. This review is not about whether Haq is a “good film”. It is about the tensions, silences, contradictions, and possibilities within its feminist aspirations.

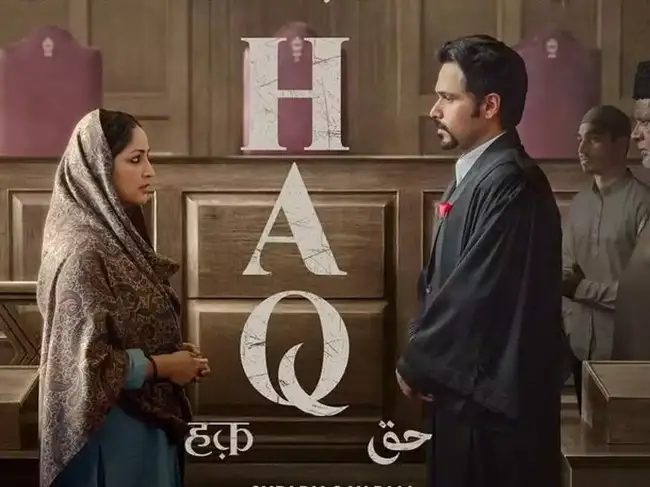

Haq: a love story that was never equal

The film introduces Abbas and Shazia as a “winsome couple”. He is a successful, modern lawyer; she is a homemaker with opinions (the cinematic equivalent of saying she is mildly progressive but still tolerable). From this author’s perspective, this is already a power imbalance. The modern, professional husband and the stay-at-home wife are not a “cute dynamic”; it is patriarchy camouflaged as middle-class normalcy.

Shazia is not simply a wife who stays at home—she is a Muslim woman, raised in a traditional community where religious ideals are invoked to maintain social status and familial duty. Her father, a “progressive” Muslim man, is still portrayed as her source of legitimacy. This reinforces an insidious cinematic trope: a Muslim woman gains respect only when stamped with approval by a progressive man. Her autonomy is contingent, granted, rather than inherent.

The film claims Shazia has a “direct relationship with God,” unmediated by clerics. But does she have a direct relationship with herself? With her inner voice? With her own desires? A feminist would argue that the film mistakes religious autonomy for personal autonomy. A woman who negotiates her faith on her own terms is still constrained if her life choices remain dictated by a husband, a father, and a society that defines her value through domestic obedience.

The early sequences romanticise Abbas’s charm, intelligence, and power. But love in patriarchal societies—especially in communities where marriage is tied to social honour—often functions as a velvet trap. Shazia’s dependence on Abbas is not emotional vulnerability; it is structural vulnerability. And the film, despite its progressive tone, never fully interrogates this.

The second wife in Haq as a plot, not a person

When Abbas brings home a second wife, the film treats her less as a person and more as a symbol of betrayal—an intrusion into Shazia’s stable life. But intersectional and Islamic feminist frameworks ask: why is the second wife always a threat to the first wife and never to the man who orchestrates the betrayal? The tension between wives is a patriarchal invention. Polygamy (always and majorly serving a man, of course), as practised in many societies, is less a religious allowance and more a deeply patriarchal act of exercising control over women’s bodies, labour, emotional energy, and reproductive capacities. I would insist: the problem is not the second woman; the problem is the man who believes he has the right to acquire women the way he acquires appliances.

To critique only the patriarchy within the minority community while leaving majoritarian patriarchy untouched is a politically convenient choice. Haq movie enters the cultural space at a time when the Indian state is aggressively curating stories about Muslim women—stories of suffering, betrayal, and patriarchal captivity, often framed through a saviour narrative orchestrated by majoritarian politics.

Indeed, the film’s own “pressure cooker metaphor”—Abbas prefers to “replace” rather than “repair”—neatly exposes the commodification of women within patriarchal marriage. But what does Haq do with this metaphor? It uses it to make Abbas villainous in a personal, moral way.

What it does not do is interrogate the system that makes such replacement possible, legal, culturally permissible, and socially normalised.

This is where Islamic feminism offers a vital critique: polygamy is not a divine entitlement; it is a historical, socio-cultural practice interpreted through men’s interests. Many Islamic scholars argue that the Quran permits polygamy only under strict conditions nearly impossible to meet—and that justice between wives, as mandated in the Quran, is a standard no man can realistically achieve. But the film does not engage with this scholarship. Instead, it perpetuates the idea that Muslim women remain trapped primarily by clerics and husbands, ignoring a tradition of Islamic feminist interpretations that centre women’s rights, consent, and dignity.

Leaving the house: the first act of resistance

Shazia’s decision to leave her marital home is framed as a moment of personal awakening. But intersectional feminism demands we see this act not merely as individual rebellion but as rebellion constrained by extreme vulnerability. A Muslim woman stepping out of marriage faces everything: community stigma, economic precarity, social isolation, legal ambiguity, state mistrust, and the weaponisation of her story by political actors.

Shazia is not simply “walking out”. She is stepping into a war zone where she is both the foot soldier and the battlefield. Her decision to seek maintenance is not a “fight for dignity”; it is a fight for survival. But here lies a deep problem: Haq uses Shazia’s rebellion to prove a point about gender justice while largely sidestepping the messy socio-political terrain in which Muslim women navigate their survival. The personal, political, religious, legal, and communal dimensions of her life collapse into a courtroom drama, flattening complex realities into digestible narrative arcs.

Triple Talaq as spectacle: who benefits from this debate?

In Varma’s film, Abbas invokes instant triple talaq to escape financial responsibility. This triggers a courtroom battle that becomes a national debate—a narrative strategy clearly inspired by the Shah Bano moment. But unlike the actual case, where the issue was maintenance and not talaq, the film focuses on the sensationalism of instant divorce.

Why is the second wife always a threat to the first wife and never to the man who orchestrates the betrayal? The tension between wives is a patriarchal invention. I would insist: the problem is not the second woman; the problem is the man who believes he has the right to acquire women the way he acquires appliances.

This is not a small narrative deviation; it is a political framing device. A postcolonial feminist lens identifies the danger here: Muslim women’s suffering is often weaponised to undermine Muslim communities themselves. Yes, instant triple talaq is unjust and patriarchal. But who turned it into a national obsession? Who uses it as evidence of Muslim backwardness? Who turns Muslim women’s pain into an electoral strategy?

In reality, the Indian state’s interest in Muslim women’s rights has always been selective, strategic, and deeply hypocritical. The same apparatus that celebrates criminalising instant talaq also restricts women’s agency in countless other spheres, targets Muslims through surveillance and citizenship laws, silences dissent, and controls women’s bodies through nationalist narratives.

Thus, the film’s critique of clerics and patriarchal interpretations of religion is valid but incomplete. It critiques the patriarchy within the minority community while remaining largely silent about the majoritarian patriarchy that creates the social conditions in which Muslim women are doubly marginalised. It is feminism without anti-oppression politics—an incomplete feminism in one’s view.

The courtroom in Haq is portrayed as a rational, secular space where truth prevails. This is a cinematic fantasy. The Indian legal system is not neutral, not today, not ever; it is shaped by caste, religion, class, gender, and political power. Muslim women often face additional barriers, including bias against their communities, lack of access to quality legal representation, fear of community backlash, economic dependence, and mistrust of state institutions.

The film celebrates Shazia’s legal victory, but the victory itself is predicated on her ability to speak perfect legal language, quote the Quran, strategically position herself as enough of a victim to win empathy without appearing threatening, and operate in a system designed for people wealthier and more connected than she is.

That is not empowerment; it is survival through performance.

One of the film’s strengths is its assertion that Shazia’s education is her unseen power. But even here, the narrative risks romanticising education as a feminist cure-all. Education helps women understand their rights, yes. But education alone does not dismantle oppressive systems that operate through law, family, religion, and state politics. Mere knowledge is not enough if patriarchal structures remain intact. And knowledge of scripture is a feminist weapon only if communities recognise women as legitimate interpreters of religious texts—and most patriarchal contexts still resist that. We are forgetting that educational access is unevenly distributed by class, caste, region, and community. Thus, while education is vital, it cannot be framed as the singular anchor of Shazia’s empowerment.

Haq’s Male characters: patriarchy with a gloss of reasonability

Abbas, played by Emraan Hashmi, is written as charming, articulate, and intellectually sharp. This is a deliberate choice. The film wants to show that patriarchy does not require brutality; it can operate through love, charisma, and legal expertise. This is an important point. But where the film falters is in humanising him to the point where his ideological violence becomes digestible.

He is not a man trapped by societal norms; he is a man who benefits from them. The “progressive father” figure, too, is a cinematic trope: the good Muslim man who validates secular, feminist values. But this reinforces the idea that Muslim women need male patrons to be legitimate political actors. A film of this stature should not make women’s liberation dependent on the moral righteousness of men.

The political silence at the heart of the film

This review must address the film’s biggest contradiction: its invocation of the Shah Bano case while sidestepping the political consequences that followed. Almost all major male characters are played by Muslim actors, while all the major female Muslim characters are played by non-Muslims in India. This is Mumbai. You can not throw a stone in one street without hitting at least ten actors with real-life Muslim experience.

This film creates the impression that Muslim women need saving from Muslim men while facing competition with non-Muslim women. The Indian state—particularly the current political dispensation—is implicitly positioned as the saviour.

One can appreciate Yami Gautam’s performance and highlight it as one of the best she has seen this year. But one must ask, where is the intersectionality that supports her Muslim sisterhood by letting them come to the forefront and letting them tell their own stories? By refusing to engage with this, the film sanitises the political landscape. This silence is not accidental; it is ideological.

To critique only the patriarchy within the minority community while leaving majoritarian patriarchy untouched is a politically convenient choice. Patriarchy is nothing without its enablers. This film creates the impression that Muslim women need saving from Muslim men while facing competition with non-Muslim women. The Indian state—particularly the current political dispensation—is implicitly positioned as the saviour.

This is not feminist storytelling. This is nationalist appropriation masquerading as empowerment.

In conclusion, Haq wants to be a feminist film. It succeeds in portraying a woman’s journey of resistance. It fails in recognising the breadth of the structures that constrain her. From an intersectional feminist perspective, the film exposes how gender, religion, and state power collide—but it also risks reproducing harmful narratives about minority communities. It critiques patriarchal marriage but stops short of questioning marriage as a patriarchal institution altogether. It reveals how Muslim women’s rights become political battlegrounds but avoids interrogating majoritarian co-optation of those rights. It highlights misinterpretations of faith but fails to seriously engage with Islamic scholarship that centres women as authoritative readers of scripture.

In the end, Haq is a film that wants to say: women’s rights are not granted; they are seized. But a more honest feminist interpretation would add that women seize rights not from individual men but from the entire empire of patriarchy—religious, legal, cultural, political, and nationalistic—that claims ownership over their lives.

Shazia’s story matters. But so do the stories of the millions of Shazias whose lives the state, society, and cinema continue to appropriate. And until those structures are addressed, no legal victory, no courtroom speech, and no cinematic narrative can be called truly feminist.

About the author(s)

Harshi is a writer and LGBTQ+ rights activist. She is also a self-identified singer. Her preferred pronouns are she/they and she identifies as a Non Binary Transwomxn. Raised to be someone who should just accept the norm , she has spent the last decade reading and writing about eccentric people and their experiences around her. Harshi has completed B.A.(HONS.) English from the University of Delhi and M.A. in English from Amity University. She cautions anyone who is thinking of doing the same. She thinks she is a realist, she still hopes to see some good change in the history of Human Rights in her country with a little contribution from her writing and activism. You can find her on Instagram- iamharshib.