This report was produced as part of the WEAVE project, a collective endeavour by feminist researchers, activists and activist-researchers from four countries – Australia, India, Nicaragua and South Africa – to document women’s movements against sexual violence and their impacts on policies and legal frameworks in our respective countries.

The WEAVE India research report traces the history of Indian women’s movements against violence through the voices, stories and standpoints of those who were in the thick of some key struggles that mark inflection points in the evolution of a feminist politics of resistance.

The study highlights these dynamics through detailed mapping of some landmark struggles, starting from the flashpoints and back-stories, and tracing subsequent actions and events in the courts, on the streets, in movement spaces, the media, the public sphere, state institutions and policy spaces. Changes in the larger landscape—the expansion of feminist framings of justice and accountability and the evolution of movement strategies of mobilisation and alliance-building—are surfaced through these storylines.

The India report is a container for a virtual archive of women’s movements against violence. It weaves together multiple sources and strands of enquiry: oral histories and personal accounts from movement actors, commentary and critiques by feminist scholars, accounts in popular media, campaign materials, court proceedings, judgements, audio-visual records and a range of formal and informal writings from diverse sources.

The report highlights the way in which the experiences and insights of women’s movements and feminist activists contributed to our understanding of the system that underpins and sustains sexual violence. The picture is like a jigsaw, with new pieces continually being added and new patterns surfacing, pushing us to expand, deepen and complicate our analysis.

The feminist understanding of the systemic roots of violence has moved far beyond the initial conversations on patriarchy and how it is baked into social structures and institutions as an unquestioned norm. Movement activists and feminist scholars have together unravelled the historic connections between caste, patriarchy, economic power and state power, all of which operate through caste endogamy and control of women’s sexuality, and are legitimised and enforced by the state.

The term ‘brahminical patriarchy’ reflects this understanding. This analysis has been further complicated by queer feminists and their allies, who have argued that along with caste endogamy and control of women’ sexuality, compulsory heterosexuality is essential for the perpetuation of the family, caste hierarchies, property relations and economic hierarchies, as well as for the survival of the state. ‘Brahminical heteropatriarchy’ is thus a more accurate term.

The report turns a feminist lens on the network of social institutions that are involved in the controlling and policing of sexuality, caste endogamy and gender identity, and are legitimised and protected by the state and state institutions. The heteronormative patriarchal family is at the heart of this system, in which control is brought to bear on women, girls and queer people to keep them in their proper place: as docile and unquestioning subjects of custody. Legitimacy for the idea of women as perpetual subjects of custody and control is sought in religious texts, concocted histories and self-serving traditions. Control and custody are framed as “love”, “care” and “protection”.

The violence built into these notions becomes visible only when they are challenged or resisted by “unruly women” – women who marry outside their caste; women and girls who resist or try to leave a marriage; women with mental illness or intellectual disabilities; women who are “rescued” from illegal or “immoral” situations; or simply women who threaten the established order by their refusal to conform, their rejection of prescribed norms and rules, their insistence on asserting their rights, or their habit of confronting and challenging power-holders inside and outside their families.

Feminist struggles and women’s movements have given us a detailed and up-close picture of the operational mehanisms by which the state enforces existing hierachies of gender, class, caste, and religious identity from which it draws its own power. The report tracks the ways in which natal and marital families, caste and community institutions, the medical system, the courts, prisons and care institutions are allied in enforcing this regime of custody and control. Personal stories, case records, official data and independent research are cited to show how sexual violence is normalised and legitimised by criminalising women’s autonomy and agency.

The narrative follows the trajectory of women’s movements against rape and sexual violence and their impact on laws and legal frameworks. Starting with the Mathura rape case in 1979 and the amendments to rape law that followed it, to the Justice Verma Committee and the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013, the journey is signposted with landmark cases that became flashpoints for women’s movements to mobilise and demand justice. Many of the unfinished agendas, unresolved questions and unmet demands raised by these movements continue to resonate for us today, and are still being raised and pursued by feminist lawyers and women’s movements in courts and public forums.

Women’s movements have exposed the extent to which class, caste and communal biases play out in the legal system. These mobilisations and critiques have led to significant changes in the legal and legislative framework on violence against women. At the same time, they have also raised uncomfortable questions around our positions on caste violence, our understanding of intersectional oppressions and our practices of solidarity across identities.

A decade after the Justice Verma Committee report and the 2013 amendments in criminal law, the rape and death of a young Dalit woman in Hathras forced us to look back and ask whether these changes had made the road to justice any smoother. The questions raised by Dalit feminists around the Hathras case brought caste issues within movements into sharp relief, proving the point that theorising intersectionality is easier than practising it. Dalit scholars are challenging feminist researchers on questions of authenticity and representation, and are calling for the active participation of Dalit women in theorising gender and feminism.

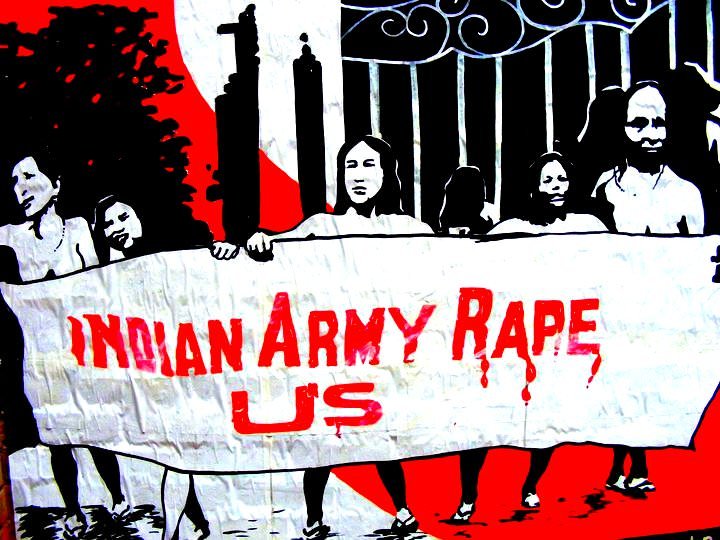

The report turns a feminist lens on the discourse of majoritarian nationalism and its weaponisation of sexual violence. The “othering” and demonisation of people at the margins of the nation has enabled and fuelled the cold-blooded incitement of hatred and violence against them. Women’s movements have mobilised against sexual violence in Gujarat in 2002 and against AFSPA in Kashmir and the North-Eastern States and are now confronting a wave of violence and hate that seems to be engulfing the whole country.

Against this bleak backdrop, the report chronicles some of the powerful and transformative movements that have shaped our politics. The Bodh Gaya land struggle, the anti-nuclear movement in Koodamkulam, feminist publishing and the “women in print” movement, the Shaheen Bagh saga, the struggle of the women wrestlers against an abusive strongman, the ASHA workers strike for respect and dignity … these are some of the many stories of resistance and resilience that give us the strength to hold our ground and carry on. We heard it in Shaheen Bagh: “We are like grass – we grow everywhere.”

Download the WEAVE India Report here.