The past month has seen an administrative embarrassment in the capital city of India as the world watched the Delhi Police manhandle a rape survivor who sat with her mother outside the courts demanding justice, again.

On 23rd of December 2025, the High Court of Delhi suspended the life sentence of four-time Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Kuldeep Singh Sengar, in the infamous 2017 Unnao gangrape case of a minor. The then sitting MLA is reported to have raped the minor at his residence on June of 2017 and amid suspicion of police action and intimidation, the case was transferred to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in April 2018, shifting the trial to Delhi as per the Supreme Court’s (SC) instructions.

This was stayed by a three-judge bench of the SC on the 29th of December after the CBI challenged this order arguing that an MLA holds constitutional office, exercises public power, and should therefore be considered a public servant.

In September of 2019, Sengar was convicted by a trial court and sentenced to life imprisonment. While a conviction is an automatic end to the “presumption of innocence”, the sentence remains open to be appealed. While the appellate scrutiny is pending, the convict may seek suspension of the execution of the sentence and bail, if in custody, avoiding the sentence time.

Two notable factors are that first, the “suspension of sentence” is just a delay in the execution of the punishment, not a pronouncement of the convict being “not guilty”. Secondly, the SC itself noted how the case raises substantial questions of law and the absurdity of the fact that a police constable is considered a public servant, but not a legislator.

It is in parallel to these legal anomalies that the dismissal of the survivor, her mother and activists by the paramilitary personnels, blocking them for communicating with the media and forcing the elderly women to jump off a moving bus reflects an appalling state of affairs.

‘We did not get justice‘ says Unnao survivor’s mother

The “suspension of sentence” is a discretionary judicial power involving short-term or fixed-term sentences where it is the norm and in serious offences, where it is the exception. The latter generally involves a life sentence. Barring exceptional circumstances, a short-term sentence can be suspended when in appeal as per the SC’s verdict in Bhagwan Rama Shinde Gosai vas State of Gujarat (1999).

The “suspension of sentence” is a discretionary judicial power involving short-term or fixed-term sentences where it is the norm and in serious offences, where it is the exception.

However, following Section 389 of the Criminal Code of Procedure (CrPC) which is now Section 430 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, suspension of sentence is a rare order only to be passed after a careful assessment of factors. Sentenced to life for the gangrape of a minor, Sengar’s case falls into this category.

In a 2024 acid attack case, Shivani Tyagi vs State of Uttar Pradesh, the SC stated that nature and gravity of the offence must be considered while determining the desirability of release on bail.

The Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnels claimed that the permission to protest at India had not been granted to the survivor, her mother and the lawyer activist Yogita Bhayana. With no female CRPF officers in the bus, the three were detained and when the mother came close to the gate of the bus, the officers were seen elbowing her, asking her to jump off and when she did, the bus drove away with the survivor.

In a statement to the media the mother said, ‘We did not get justice. My daughter has been held captive. It seems they want to kill us. CRPF men took the girl and dropped me on the road. We will give up our lives‘.

The officers claimed that the survivor was being taken to her home where she has been living under CRPF protection following a series of tragedies, involving intimidation and murder in her family, over the past eight years.

The officers claimed that the survivor was being taken to her home where she has been living under CRPF protection following a series of tragedies, involving intimidation and murder in her family, over the past eight years.

‘How can the judiciary do this to us?‘

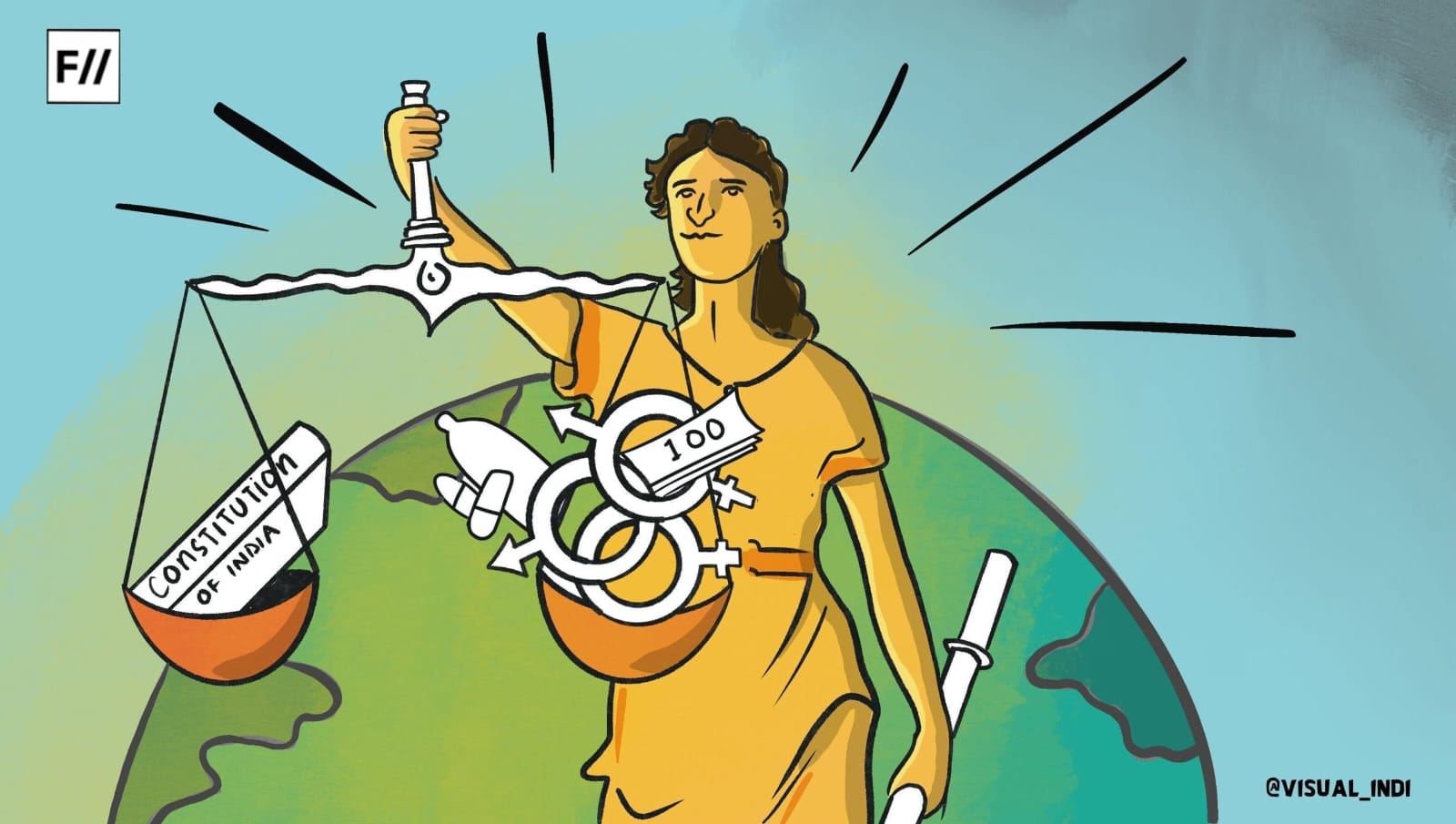

The Delhi High Court allowed Sengar’s suspension of sentence focusing on his conviction under Section 5(c) of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012 which criminalises ‘aggravated penetrative sexual assault‘ by a public servant on a person aged less than eighteen years of age and the punishment is stated under Section 6. Criminal law segments say that offences committed by persons in position of authority such as the police, public servants, staff of hospitals, jail, or educational institutions are to be considered ‘aggravated‘ and they are to be punished strictly for having exploited the vulnerability of the victim, given the status hierarchy.

While the term ‘public servant‘ is undefined in the POCSO Act, the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860 defines it as a person occupying the category of judges, military officers, police, election executives et cetra who are not elected as legislators, under Section 21.

Relying on the case, RS Nayak vs AR Antulay (1984), the Delhi HC held that Sengar, a four-time MLA, is not a ‘public servant‘ under the IPC and hence, also the POCSO Act. The trial court, in 2019, had instead referred to Section 2(viii) of the Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA), 1988 which considers any person holding an office to perform public duty as a ‘public servant‘.

Holding that by this fact Sengar’s case does not fall under Section 5(c) of the POCSO Act or Section 376(2)(b) of the IPC, the “suspension of sentence” was granted. The HC also took note that he had served his sentence for over seven years and relied on Kashmira Singh vs State of Punjab (1977) to hold that prolonged incarceration could cause injustice if conviction of the sentence was later modified.

The survivor, in a statement to the press, exclaimed shock and was determined to demand an emergency hearing in the SC. She said, ‘How can the judiciary do this to us?‘, and out of obvious apprehension given the documented history of systemic intimidation, she added, ‘This Kuldeep Singh has the money and power to get his way, and we have to suffer.’

She said, ‘How can the judiciary do this to us?‘, and out of obvious apprehension given the documented history of systemic intimidation, she added, ‘This Kuldeep Singh has the money and power to get his way, and we have to suffer.’

Sengar was also convicted under Section 304(II) of the IPC for the custodial death of the survivor’s father, police callousness and the 2019 truck-car collision that killed her two aunts. The protection from CRPF was granted after this in August 2019.

Yet, the Delhi HC held that “suspension of sentence” cannot be denied on the apprehension that the paramilitary forces or the police will fail to perform their duties.

‘My family is not safe‘

The Delhi HC is correct in recusing itself from elaborating the definition of ‘public servant‘ but the anomaly in the POCSO framework was flagged by the SC as well. However, activists contend that offences under Section 5(c) are much graver than corruption charges on legislators under the PCA. Moreover, POCSO being a victim-centric statute particularly enacted to protect children, must consider the severe physical and psychological trauma caused to the minor, having long-term social consequences for her.

In Attorney General for India vs Satish (2021), the SC severely cautioned against the literal interpretation of the POCSO in a case where groping a minor over their clothing without ‘skin-to-skin‘ contact was held as not amounting to ‘touch‘ or ‘physical contact‘ and hence, the offence of sexual assault did not come under Section 7 of the POCSO Act. A similar course was taken by the apex court in criminalising marital rape when the wife was aged between 15 to 18 years, in the case of Independent Thought vs Union of India (2017).

Recently, in the case of Chhotelal Yadav vs State of Jharkhand (2025), the SC held that “suspension of sentence” in cases involving life imprisonment is warranted only when a fair chance of acquittal was undermined and a gross error in the trial court’s judgment was enough to show that the appeal may succeed and result in acquittal. In Sengar’s case, long incarceration and Section 5(c) alone were considered as reasons enough for the grant of “suspension of sentence”.

This dismisses several other proven charges of intimidation, threat, witness tampering and violence. The mother of the survivor said to the press, ‘We’re fighting for justice for 9 years, and I lost my husband in the process. Police intimidate us, manhandle us. My family is not safe.’

New battles in the new year for the Unnao rape survivor

This stay by the SC is not the end but the beginning of another ordeal for the survivor and her family. On the CBI’s appeal, the SC has issued notice to the HC and this case will be formally admitted for reconsideration in the apex court, where both the sides will present their arguments again. The stay shall continue indefinitely for now until removed by the SC or after the decision that comes out of the appeal.

On the CBI’s appeal, the SC has issued notice to the HC and this case will be formally admitted for reconsideration in the apex court, where both the sides will present their arguments again.

The court has given Sengar four weeks to file a counter affidavit, the CBI will most likely present rejoinder to it and detailed hearings will follow to determine whether:

- MLAs are ‘public servants‘ under the POCSO Act,

- this case is that of an aggravated sexual assault, and

- the Delhi HC was right or wrong in granting the “suspension of sentence’.

The case also opens the possibility of a legislative reconsideration on who all the term ‘public servant‘ entails. However, even if it is expanded, laws are not enforceable retrospectively unless exceptionally made to.

For the judiciary, this is a legal and moral challenge given that justice presumed to have been served, now seems to be delayed and denied. Finally, for the justice delivery mechanism of India, this is another case in history where survivors of sexual violence continue to “survive” everyday, battling retraumatisation by the system.

About the author(s)

Second year student of Media Studies at CHRIST (Deemed to be University), BRC, Bangalore. A trained Kathak dancer, theatre artist and political nerd.