Rama Duwaji is not new to conversations around feminist art, diaspora, and political resistance. But her recent surge in public visibility following the felicitation of her husband, Zohran Mamdani, as Mayor of New York City, has placed her work in an altogether different kind of spotlight. No longer circulating only within the familiar digital economies of activist art and illustration, Duwaji’s work now exists in close proximity to formal power. Her presence in the role of First Lady raises questions that reverberate far beyond New York, including feminist movements in India grappling with their own contradictions around representation, institutional capture, and the aestheticisation of dissent.

What does it mean when art born from the margins enters the mansion? Can feminist practice retain its political edge when it becomes adjacent to state power, or does visibility risk neutralisation? And perhaps most critically, does visibility within institutions translate into transformation, or does it merely offer the theatre of inclusion?

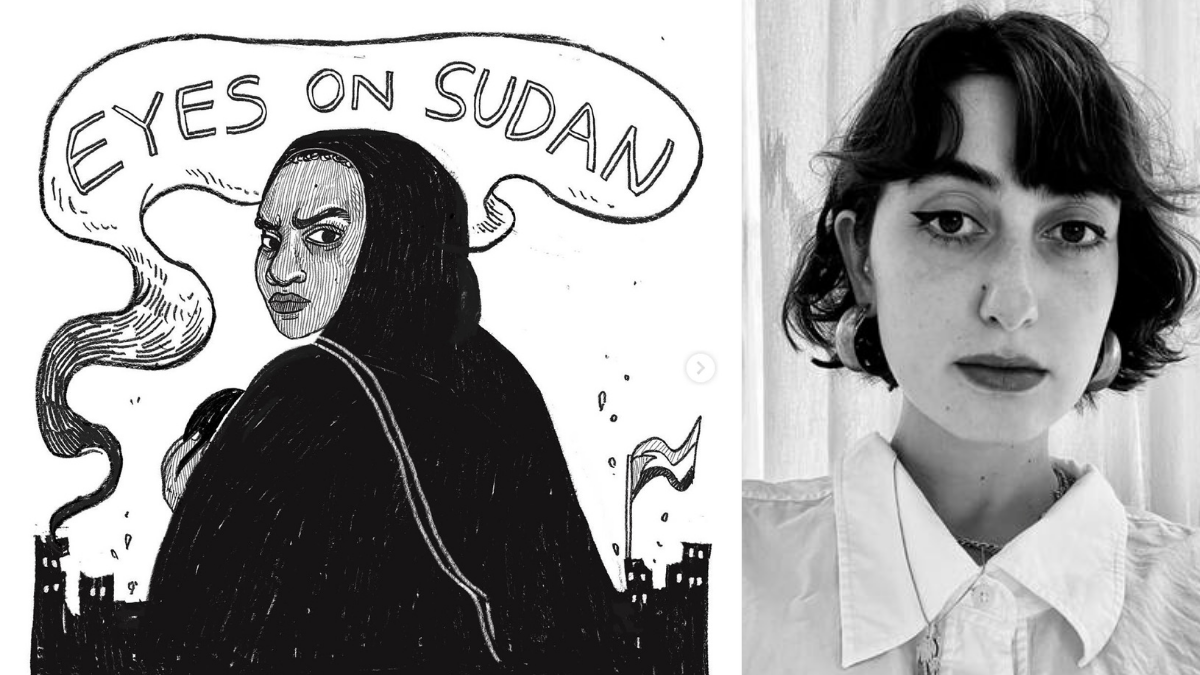

Duwaji’s illustrations have long circulated online within an ecosystem of feminist visual culture. Her work, marked by thin lines, soft colour palettes, and what many have described as a “modernist” sensibility, often depicts intimacy, collective life, domestic care, protest, and political grief. These are not spectacular images of resistance. There are no grand revolutionary gestures here. Instead, Duwaji’s politics lie in the everyday: bodies leaning into one another, women holding space, acts of care rendered as quietly radical. Women with coarse curls, prominent noses, and defined eyebrows feature heavily in her drawings. Her portfolio includes soft images of womanhood alongside weightier works depicting the war in Gaza and revolutionaries killed in Syria. These are deeply situated investigations into how power shapes everyday existence, particularly for women navigating displacement, occupation, and loss.

This aesthetic of engaging with politics has travelled widely through digital platforms, particularly Instagram, where feminist art has become one of the most visible and most contested modes of political expression in the last decade. Such platforms enable rapid circulation but also produce a flattening effect, in which political art risks becoming shareable, consumable, and easily detached from its material conditions.

What changes, then, when this kind of art becomes associated indirectly with state power? As the First Lady of New York City, Duwaji occupies a symbolic position that is deeply gendered and historically conservative. The political spouse is expected to perform warmth without dissent, elegance without opinion, and presence without power. In this sense, the role is not neutral. It is a site where femininity is disciplined into decorum, and where silence is often mistaken for grace. What makes Duwaji’s position striking is not simply that she refuses this script, but that her refusal is enacted through her art and her deliberate absence from campaign events.

Unlike many candidates’ wives who hit the circuit with their spouses, Duwaji frequently didn’t appear at campaign events and fundraisers. When she taught a previously scheduled workshop on the night of a mayoral debate, the internet hailed her for skipping her husband’s “boring work event”. Against this backdrop, Duwaji’s continued identification as an artist, rather than a “plus-one,” becomes politically significant. As she notes in a recent interview, she has been deliberate about resisting the reduction of her identity to marital proximity, insisting instead on being recognised on her own terms as a working artist.

Duwaji herself articulates the tension of the role with striking clarity. As she told The Cut in an interview, “Even the word wife feels very intense. I just feel like a forever girlfriend.” When asked about becoming First Lady, she paused before responding: “It is surreal to hear. I think there are different ways to be First Lady, especially in New York. When I first heard it, it felt so formal and like — not that I didn’t feel deserving of it, but it felt like, Me…? Now I embrace it a bit more and just say, ‘There are different ways to do it.’”

What distinguishes Duwaji’s practice is her sustained commitment to care as a political category. Feminist theorists have long argued that care is systematically devalued because it is feminised and is associated with domesticity, emotion, and reproduction rather than governance or authority. By centring care, Duwaji’s work challenges the very grammar of political power. Her illustrations do not aestheticise the state; they do not monumentalise leadership. Rather, they gesture toward alternative forms of collectivity like networks of intimacy, solidarity, and shared vulnerability that exist despite, and often in opposition to, institutional frameworks.

In this sense, her art does not become ornamental simply because it circulates near power. Care, unlike ornament, makes demands. It insists on accountability. It asks who is held, who is abandoned, and who is rendered disposable. As Duwaji herself has articulated in an interview, speaking out about Palestine and other sites of ongoing violence is not optional but integral to her practice; it would feel “fake” to produce art divorced from these realities. This insistence on political continuity matters in a moment when institutions are eager to celebrate feminist presence while disciplining feminist critique.

Duwaji’s art is deeply shaped by diasporic experience. Born to Syrian parents and raised across the United States and the Middle East, her work resists fixed national belonging. It traces affiliation through memory, language, and shared precarity. Women with prominent noses, thick eyebrows, and coarse curls populate her illustrations and are not simply exoticised figures. They are intimate subjects rendered with familiarity and care.

Diaspora in mainstream political narratives is often mobilised as evidence of successful assimilation: proof that the state is inclusive, diverse, and progressive. Duwaji’s work quietly refuses this framing. It does not smooth over histories of displacement or Islamophobia; nor does it translate them into liberal optimism. Growing up Muslim in post-9/11 America shaped her political consciousness early, making neutrality impossible (The Cut). By maintaining this diasporic memory within spaces of institutional visibility, Duwaji unsettles celebratory narratives of representation. Her art insists that belonging is not granted by proximity to power, and that visibility does not erase vulnerability.

Years before the media began scrutinising her wardrobe choices, Duwaji understood clothing as an extension of her art and politics. Her black turtlenecks and pixie cut, which Vogue called fall’s new ‘cool-girl’ look, have launched countless TikTok fan edits. But this aesthetic legibility is inseparable from political intention. As she explained to The Cut, “It’s nice to have a little bit of analysis on the clothes because, for instance, during the general-election night, it was nice to send a message about Palestinians by wearing a Palestinian designer, Zeid Hijazi, whose black top she paired with a skirt by New York fixture Ulla Johnson. This approach extends beyond individual garments to a curatorial sensibility about representation itself.

For her first cover shoot as the First Lady of New York, Duwaji wore a mix of young designers alongside New York-based, POC-owned, and vintage brands, all on loan. She even wore ceramic hands made by photographer Szilveszter Makó, directly invoking her own artistic practice. The choices reflect the same attention to provenance, politics, and community that animates her illustrations: a refusal to separate aesthetic decisions from questions of who is being supported, what narratives are being reinforced, and what solidarities are being enacted. Her sartorial choices resist the feminised expectations of the political spouse. In this sense, her clothing becomes another site of feminist resistance to be visually consumed on terms set by the state or the media.

Duwaji’s work reminds us that art can be a form of witness, of care, of sustained attention to lives shaped by power. Whether it remains so when proximate to institutions depends less on the artist than on the movements and communities that refuse to let critique be neutralised, that demand substance over symbol, and that insist that visibility is only meaningful when it opens space for transformation rather than forecloses it.

In the end, feminist art in spaces of power must be measured not by its proximity to institutions, but by its continued capacity to make those institutions uncomfortable, to insist on questions they would prefer to remain unasked, and to maintain solidarity with those who remain outside the mansion, even as some move through its doors. Her duties as First Lady, she maintains, “are in essence the same as the ones she has as an artist with a platform” (The Cut). The question for feminist movements is whether institutions will allow this equivalence to hold, or whether the mansion will inevitably domesticate what once circulated as resistance.

Reference List

- Care Ethics and Paternalism: A Beauvoirian Approach, MDPI

- In conversation with Rama Duwaji, Shado

- The Artist in Gracie Mansion, The Cut

- Rama Duwaji